Two years ago, I wrote a post called “Fear and the English language“. It was my twist on George Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language, in which Orwell, in his timeless way, indicts and mocks modern writing.

Two years ago, I wrote a post called “Fear and the English language“. It was my twist on George Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language, in which Orwell, in his timeless way, indicts and mocks modern writing.

“The whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness,” Orwell said.

But why is this so? Because we are afraid, I concluded (after interrogating my own brain as it writes). We are afraid of the consequences of our words — of being misunderstood or attacked — so we make the words less clear. We use our words to erect barriers to meaning so we can hide behind those barriers.

This is cowardice. And it leads to bad writing, and bad speaking.

That covers most of verbal communication: the corporate memo, the annual report, the government publication, the politically correct academic thesis, the conference call with dial-in numbers, etc etc.

Well, that old post seems to have resonated, especially with those of you who also write for a living.

One of you, Eliot Brockner, emailed me this:

… I just read a post of yours from a few years ago titled “Fear and the English Language” and felt compelled to write you because of its relevance and timeliness in my own thoughts and struggles to grow as a writer. I think part of the problem is that what I write on a day-to-day basis by nature involves writing with fear. The company I work for covers operational threats to our clients’ businesses (I cover Latin America). To account for any possibility or event, I must use words that make for bad writing – ‘may’, ‘possibly’, ‘likely’. Even though our content is event driven, very little of what we write is concrete.

My problem is that because this type of writing takes up most of my time, my own freelance work – my blog, my writing for other digital publications, even my own personal writing – is suffering. Having to account for so many possibilities in my professional writing is clouding my clarity of thought, and without clarity of thought, clarity of writing is impossible.

How do you break this mold? If you are writing with fear, how do you stop? I’m having trouble reconciling the professional and personal writing worlds.

So Eliot poses the obvious next question: How do you stop writing with fear?

I gave Eliot the honest answer, which is that I have no good answer. (Remember, this is a blog, and most of the time I post stuff that is on my mind, unresolved, not stuff that I have already resolved.) But I promised that I would open it up here, to “crowd-source” it. So weigh in below.

As I ponder Eliot’s challenge, I follow a chaotically dialectical mental trajectory as follows:

1) Arise, inner Hero

Psychologically, writing usually begins as a Quest.

I capitalize Quest to remind you of the archetypes in the thought of Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell. In a writerly Quest, the (usually youthful) writer necessarily sees him or herself as a Hero/Heroine. I had a long-running thread on heroism here on The Hannibal Blog, so let me just pluck from that series two very clean and simple kinds of hero:

- Theseus in antiquity or

- Germany’s White Rose in modernity.

One kind of writer, after reading Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, seethes with bravery and becomes Theseus after he moves the boulder and finds his father’s sword: He wants to go out and prove himself, to slay villains on the way to Athens and then the Minotaur.

Another kind of young writer becomes The White Rose and decides to challenge evil with courageous words, by telling truth to power, by not shutting up, risk be damned.

To pick, somewhat arbitrarily, two analogous examples from our time:

- Chris Hitchens might be a Theseus;

- Paul Krugman might be a White Rose.

In Hitchens’s case, we see a self-conscious hero dazzling us with his word prowess right from the first line of anything he writes. He knows he will have enemies (the whole point is to make enemies!), so he tilts at them with a cavalier smirk, with utterly gratuitous bravado, and says “bring it on.” Whatever you think of him, whether or not you agree with him, he regularly overcomes his fear and writes well. Orwell would approve.

In Krugman’s case, he sees (in much less intense form) in American Conservatism what the White Rose saw in Nazism: a curse to be opposed with relentlessly clear polemical writing. He does not hedge, he does not mince, he does not dilute or duck or hide. Whatever you think of him, whether or not you agree with him, he regularly overcomes his fear and writes well. Orwell would approve.

So Eliot, you could try to be a Hitchens/Theseus or a Krugman/White Rose. To hell with clients, employers, editors, readers: excise those hedge words, make those tenses active, replace those Norman words with Saxon ones, make those thoughts as clear as they want to be.

2) Sit down, you’re no hero

But wait, Eliot: What if you’re not a Theseus or a White Rose?

Oh, and by the way, when Theseus became unpopular in Athens, somebody threw him off a cliff. And the members of the White Rose were beheaded. So what if you pick a heroic fight and … lose? You’ll still have to pay the bills and rent or mortgage.

So let’s remember that good writing is rare precisely because it is dangerous. Somebody who leaps to mind is Satoshi Kanazawa, the scientist we debated so passionately in the previous post. In our discussion, we mainly argued about his academic freedom, his integrity as a scientist, his rights and privileges in the pursuit of truth. Those are the appropriate questions.

But I also see in him the struggle we are talking about in this post. He did not want to dilute his hypotheses into the usual term-paper bilge. He wanted to make the words simple and clear. As ever, simplicity and clarity in writing make the words stronger and more powerful. And that’s what sealed his fate when he wrote the title of the blog post that suspended his career:

Why Are Black Women Rated Less Physically Attractive Than Other Women, But Black Men Are Rated Better Looking Than Other Men?

Give Eliot or me five minutes, and either of us could edit Kanazawa’s original post in such a way that nobody would take offense. How? By hiding the hypothesis behind hedges, passive tenses and qualifiers so deep that you wouldn’t even be able to find it. Kanazawa’s post would then be titled:

Preliminary implications of factor analysis on the aesthetic variance observed among gender and race phenotypes

(This sort of thing happens all the time, by the way: Coincidentally, I found another old post of mine in which I lament the New York Times doing this, with another topic vaguely mixing science, sex and race.)

The writing would be awful, yes. Orwell would not approve, except in his ironic Orwellian way. But Orwell does not own Psychology Today or run the LSE. Satoshi Kanazawa might still be blogging. This could all have turned out differently.

So maybe, Eliot, you and I are right to be circumspect. Let’s write, you know, fine, not too well. Let’s save the good stuff for later, for a special day. We would be in good company: Even Mark Twain concluded that you can only write honestly when you’ve got nothing left to lose:

Free speech is the privilege of the dead, the monopoly of the dead. They can speak their honest minds without offending.

3) If you can’t be a Hero, don’t write at all

But that’s not satisfying. I didn’t become a writer to write badly. If this is the way it is, Eliot, let’s rather not write at all.

And again, Eliot, you and I would be in excellent company: Socrates refused to write anything at all, because the written word cannot defend itself, whereas the spoken word (in his opinion) can. As soon as you write something down, said Socrates, the words will be misunderstood or distorted, by the dumb or the malicious, and your words

must remain solemnly silent.

4) If you must write, at least pick your battles

Clausewitz

But that’s not satisfying either. We became writers because we love writing, and because we do occasionally have something to say.

So perhaps, we must integrate all these strands into something practical. This brings to mind Clausewitz and the distinction between tactics and strategy.

Let’s distinguish between means and ends, between important battles and distractions and diversions, between the individual words and the intended meaning, between each instance of writing and an entire writing career.

I suspect, Eliot, that we would then:

- sometimes follow Socrates and choose not to write at all,

- sometimes follow Twain and choose not to write yet,

- sometimes compromise and choose words that make smaller targets but retain power,

- sometimes go heroic and stumble, as Kanazawa did, then get up again and keep going, and

- sometimes revert to our inner Theseus or White Rose, decide that now is the time for our arete — all consequences be damned — and write really fucking well.

I admit that I haven’t really digested your post, but being something of a writer, this topic never ceases to make my heart a-flutter. I would suggest, as I think you kinda sorta do, a multi-hero approach.

All really good writing, as I shall wantonly declare, happens in drafts, plural. Very few writers can sit down and vomit out a masterpiece. So there’s a lot to be said for charging into the unknown like a knight-errant, looking for adventure and revelation, perhaps having an idea in your head of what you seek or just galloping wherever fortune might take you (I usually fall somewhere in-between). But actually moving is the key, because that is often the hardest part. I can strangle myself with self-doubt, and if I think about something enough I will find no end of self-doubt. Now. That said, errant is the operative word. You will mess up, and it will be ugly. One of my professors called it the “shitty first draft” method. You have to accept that charging into the unknown is going to get you dirty, otherwise you’ll stay locked and hidden away in a castle.

Having sought adventure and covered myself in shit, next I become a buddha and sit on what I have done. I contemplate where I ended up, ponder if that was where I wanted to end up, reflect on how I’ve gotten there, but most of all I am still, my mind digesting. I lied; this is probably the hardest part. But it often happens that I finally get a clear idea of what I mean to say only after shelving it for a month or two. Yes, a month or two.

At this point, I become a scientist. I chart everything. Outlines of meticulous intricacies; spreadsheets—yes! spreadsheets in creative writing!—cataloging every scene, plot point, crisis, and character. Having meditated, now I know what I want to say, so I craft my themes as though they were unifying hypotheses, finding my motifs and symbols, my proofs, and entrenching them into my narrative. This is also when I cultivate my precision. If something doesn’t fit or works against my hypotheses, I grind my hypotheses down, refining my words down to elegant truths. In truth—and I mean this—it takes the most persistence, the most will; I’d have to say, as hard as the other steps were, this no doubt the hardest part of all.

Lastly, I must be a general (like Clausewitz? I admit, I do not know him …), and read everything with a mind for the war, not the little battles that make up the scenes or the campaigns that make up the chapters. I have to see everything in the big picture, and I have to make it work. I have to keep my supplies and troops in line, and then I have to make them march. I have to delegate things to my lieutenants (poor souls who made the mistake of offering themselves as readers, and so were drafted into service), and then revise my tactics to meet the knew threats they find. I have to admit that I didn’t write this just for me. I wrote it to connect to other people, so I have to ask them, “Am I connecting with you?” Need I point out that this, in fact, is the hardest part?

And then, argh—I have to let it go, release it into the wider world, leave it to be torn to shreds, let it defend itself, speak to others, commune with them, or die alone. Truly the hardest part.

Are methods are perhaps similar, Andreas?

Ha ha, *the new threats my lieutenants find … and our methods are perhaps similar, Andreas. I forgot a verb somewhere too…. That’s what I get for only writing one draft of this.

Three cheers to drafts and drafting, Chris. I’m mostly with you, except for the spreadsheet part. You should have that one checked by your medical practitioner. 😉

Seriously, drafts are crucial. I’m proud of the violence I do to my own words between drafts. I have turned bad into good with ruthless redrafting.

On the other hand, drafting does not give us an escape hatch from the fear dilemma. If you’re afraid, and ruled by the fear, you will draft yourself deeper into the evasion thicket. To draft yourself to clarity, you’d still need to resolve the issue of how courageous to be….

Words should be subordinate to thoughts but they never are. That is the perennial struggle. Minimising numbers of words helps.

Minimalism, yes. fewer > stronger, usually

I’m too scared to comment.

“…..the politically correct academic thesis…..”

Isn’t what is called “political correctness” just courtesy?

There you have it, Philippe. Too often the objection “political correctness” is used as a cover for plain rudeness and to cover an impossible position. It works both ways, of course.

Thank you Andreas for a wonderfully thought provoking post.

That is all I was going to say, but I feel obligated to respond to Phillipe. I can’t agree that political correctness is just courtesy. Political correctness is lying because, especially in the academic world, it demands the suppression of the truth.

Tact and respect aren’t lying, Thomas.

Nobody I know has ever used “political correctness” and “courtesy” as synonyms. PC is prescribed evasiveness and mediocrity designed to avoid offending by not expressing.

I fail to see—and we may be talking about two different things here—how using the word “homosexual” instead of “fag” or “person with a disability” instead of “retard” is lying.

A “fag” is a sexual deviant. A “retard” is less than fully human. Need I mention what “black person” replaces? Political correctness works to remove the bias from language and address people as autonomous individuals, which is why it’s so clunky, cuz our everyday language is really, really biased. No doubt, it can be abused, but I just don’t see how it is bad or lying in and of itself.

Seen from South Europe, I believe it to be a problem with the Anglo-Saxon culture. “You’ve got to be discreet, not direct – my Anglo-Saxon blogger friends advise me – . You have to understate, not overstate”.

Well, well, well. My father’s North-Italian culture – the Piedmontese – is like that in its own way atypical of the stereotyped Italian. In reaction to that and to him (my favourite pastime was to shock him poor dad), and because I am a Roman I am blunt and politically incorrect.

One example:

“In writing one has to treat readers badly, since readers are like women, the more you treat them badly, the more they love you”

[Of course I now know expect to be at least sued for such statement]

I do believe in this ‘treating badly’ type of thing. As a general philosophy 🙂

Unfortunately, since my readers mostly come from the diverse Anglo-Saxon flavours I have to interface with their culture. Which is fascinating, and a trap in itself – a discreet one of course ça va sans dire.

So, like with women, one wonders who captures who. But that is another story (or maybe not).

Oh thank god you’re here, MoR.

We need a good spanking. We Anglo-Saxons.

Somehow I suspect that in your hallowed universities (wasn’t Bologna the very first one?), you also have some politically correct bad Italian cluttering the desks. But perhaps Italian writers are more relaxed and free.

Your quote reminds me of the famous Nietzsche quote: As the old woman tells Zarathustra, “Thou goest to women? Do not forget they whip.”

We might paraphrase: “Thou bringest words to they readers? Do not forget thy whip.”

Nabokov was a hero when he wrote LOLITA. That’s a dangerous book about sex.

Eve Ensler’s VAGINA MONOLOGUES is no act of heroism to me. It pretends to be daring and in your face, when, really, Ensler had her finger on the pulse of American women and she told them what she knew would appeal, and appeal in a way that allowed them to feel that they were participating in something risky. Please. That’s commercial savvy masquerading as courage.

I love your ideas. I don’t agree with all of your examples.

All you’ve reminded us of there, Jenny, is that courage (“heroism”, integrity, authenticity) is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for good writing.

One still has to be original, fair, thoughtful, balanced, etc.

(Specifically about the Vagina Monologues: I never understood that particular phenomenon.)

Not at all what I said, Andreas. My comment addressed only the question of courage in writing. There is real courage and there is mock courage.

Some people might say that Ann Coulter overcomes fear to write as she does; I think it’s easy and cheap, and pawns itself off as bravery. Frequently, very frequently, I disagree with folks who find Keith Olbermann brave. He knows he has a following and speaks to that following. Where’s the courage in that?

I’ll go get my whipping now. I’m way overdue.

oh, I totally get all that.

What we have here are two different targets of concern:

1) I’m worried about writers (and speakers) who evade out of fear. I think they are in the majority, which explains the dross of today’s verbiage. And our reason for worrying about becoming like them is that Eliot asks, from a writer’s perspective, how to avoid that fate.

2) You’re worried about the vocal minority who stand out by overcompensating, by being gratuitously contrarian or offensive, which may be ANOTHER way of hiding. (In this case, they’re hiding behind bravado from the absence of an actual argument or message.)

Group 1 (which I’m addressing in this post) needs to be told to strap on a proverbial pair.

Group 2 needs to be spanked, told to do some homework and get a clue.

If I had, in this post, analyzed Group 2 instead of Group 1, I might well have concluded that Group 2 is practicing “Flucht nach vorne”, a great German phrase which I don’t know how to translate. It means something like “flight forward” or “escape by attacking”. Ie, you’ve got nothing, you’re done, and so … you attack. That’s not actually courage. That’s despair.

But again, I’m not addressing the desperate in Group 2 (I don’t think Eliot or I are in that Group, nor are you). I’m addressing the proactively timid in Group 1 (Eliot, I and you are in that group, at least occasionally.)

Eve Ensler? I thought the Vagina Monologues were by Dick Tales.

Very often, rather than despair, members of Group 2 are driven by a keen business sense. There’s money in shock-jocking. Good for them. (At this point in my life, I admire anyone who has found a way to make a decent living without having gotten themselves mired in some dreary menial labor or nine to five routine. I see Ann Coulter, I go, “Wow, here’s someone who’s making a buck just by being herself.”)

Man. Like Chris, I’m still digesting this one.

I read an article a few months ago about a psychotherapist in L.A. whose clientele features screenwriters suffering writer’s block, which perhaps incorrectly I will equate here with poor writing. His prescription? Recognize your inner demons and confront them.

One of these is hard to do, let alone both. But when they do happen, so too does fearless writing.

Group 1 here, the successful ones who say less by saying more, is the group I had in mind when I wrote that message. Why are these people in the majority? Fear is a huge factor. It could be anything, from fear of confronting one’s inner demons to fear of not paying next month’s rent.

But I also think part of it has to do with reward.

Sometimes we are rewarded for hedging. I’ve had editors essentially do to my writing what Andreas did to Kanazawa’s title in the post. And the edited, safer version is what went out (and subsequently what I was rewarded for). The big shame here is not the editors, who are doing their job. It is my silence. I’ve also been in battles where I’ve fought and won, though these are much more rare.

Andreas, your conclusion is right on. Maybe there isn’t a single solution to avoid writing with fear. Maybe we just pick our battles with the knowledge that some will be won and some lost. If we are strategic about it (in choosing whom to follow), we will ultimately come out on top.

(The article about the L.A. psychotherapist is here, for those who are interested http://nyr.kr/eOKFkh)

If you seek by your words to reconcile another’s quarrel you have to hedge, If you tell it as it is you will most likely make things worse.

Once the heat is taken away, a true compromise can be found.

I detect another great discussion (or discussions, probably) arising. A thought provoking post triggering dissent and agreement which I will simply absorb and, hopefully, from which I will learn.

I actually agree with Philippe that “political correctness” is also courtesy.. Not always, of course, because Thomas, I think is also right… it requires the suppression of truth. But courtesy is often that. The finest, stalest, example is the woman asking her husband “Does this dress make me look fat?” Courtesy (and self preservation) requires he assure her it does not. So the two concepts intertwine.

But writers should not be cautious husbands, should they?

Well, exactly, and this is where I would invoke Clausewitz and “picking your battles”: As husband, one should immediately declare self-evident slimness in all matters of spousal attire. This saves time, energy and possibly lives. And thus it makes possible the worthwhile expenditure of time, energy and life on … writing

Thanks, Douglas. The way I see is is that political correctness is not courtesy and if you think it is you are confusing cause and effect. Before the era of political correctness you could tell a polite person from an ignorant goon because they didn’t use offensive or abusive terms. So yes, a polite person will appear to be politically correct because they will not use words that society has said are no nos.

But political correctness is not the “little white lie” to avoid hurting one’s feelings.It is more than not hurting peoples’ feelings. It is the denial of truth because it goes beyond proscribed words into the area of proscribed thinking.

Here is a blunt example. Take a child with an IQ of 50. To be nice/courteous/polite, you might tell the child or the parents that he (or she) has a bright future or has talents, etc. And that’s OK because there is nothing to gain by telling the parents that the kid is slow or retarted.

But political correctness demands that we not only not call the kid slow/retarded, etc., we must also deny that the child is “different.” There are two problems with that. One, it is a lie and lying is wrong. Second, it prevents the child from getting the special care that a child like that needs and that doesn’t help anyone. (I know everyone will have an example proving or disproving what I just said, but it might be useful to just try to think about the concept for a minute before reacting).

Another example of the sacrifice of the truth to political correctness: A university publication was ordered to apologize (the standard band aid for violations of the rules) because it offended the Jewish community. It published a list of the greatest mass murderers in history based on how many people they killed. The actual point of the story was that a lot of the victims had been “turned in” by neighbours, colleagues, etc. In Nazi Germany neighbours tipped off the Gestapo, in Mao’s China children turned in parents and teachers and in Pol Pot’s Cambodia everyone turned in everyone. That is an important and interesting thing to discuss and is a source of insight into human nature..

But the discussion was lost in the firestorm of indignation because Hitler only came in third (after Stalin and Mao) on the list and a vocal protester was offended by that. The apology was issued, and the truth and the possibility of a meaningful discourse on human nature was lost. Thanks to political correctness.

I’m not advocating a world in which we go out of our way to be abusive or hurt other peoples’ feelings. I’m trying to point out that instead of going ballistic over words we should be focusing on real issues.

Because the bigger question is whether, since the start of political correctness, has the world become a better place? Is it more peaceful, safer, more friendly? I don’t think so. We might not call each other names because it isn’t nice, but our political discourse, internet commentary, television and movie discourses are shockingly barbaric. I don’t know if the homogenization of society that political correctness demands is causing a reaction of tribalism in which people have sought to accentuate and focus on the things that make them different or if the uncertainly of the rules of social interaction as a result of political correctness have made people look for certainties and community in the form of religious fundamentalism, but I certainly can’t say that the world is a better place.

Do your worst as I attempt to exercise my inner hero.

I will be terse, Thomas. Words do not only have meanings, they have connotations. It is the connotations that cause the offense. And we all agree that certain words can offend and, out of courtesy, not be spoken. But sometimes offense becomes a kneejerk reaction. A few years ago, a politician (I forget which one) used the word “niggardly”. People became offended and, eventually, the politician apologized for using a word that wasn’t offensive. That, to me, is the danger of political correctness. It grants a power that should not be granted.

And what if the child of IQ 50 does have a bright future, Thomas?

Your comment is a study of human frailty. You know too much about that for my liking.

I now have the results of a test of your comment by my semantics laboratory, Thomas.

You are a closet genocide.

You should know that in the interests of science.

It is shameful that no-one has yet defended Thomas.

Great piece. I absolutely adore that quote from Orwell about soft snow. I liked it so much I used it in my rebuttal of Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert. He criticized me for not accurately conveying his meaning. http://danbraganca.com/2011/07/01/scott-adams-narrow-pen-ctd/

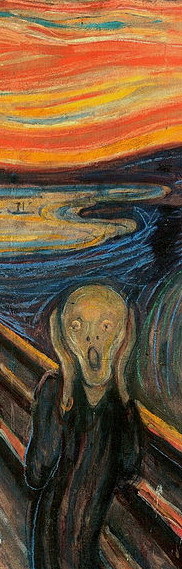

You have taken only a detail of The Scream and omitted the disinterested onlookers.

How cold they are.

I feel anger in my bones now about this debate.

What about the truth, the whole truth and….nothing but the truth.

Or is that to be abandoned in the interests of science and free speech? Yes, I do question the integrity of those who exploit the privilege.

I always keep in mind Kipling’s words when I think of true writers:

“…yet, don’t look too good

nor talk too wise.”

Writers must talk/write nonetheless albeit with the added skills of a magician.

When you talk of magic, Geraldine, do you mean serendipity – the accidental uncovering of truths – or deception?

Neither. I mean the ability to relate what one believes to be the truth in a way that others will listen without distractions. To have an audience receive and ponder the words in wonderment would be my goal.

There are two principal ways to cause offence.

Way 1: commit an outrageous injustice;

way 2: correct an error or advance knowledge – that is to say, uncover the truth.

It is generally accepted that the first is wrong and may need to be curtailed and that the second is permissible.

In any particular instance the difficulty is how to classify it. Merely to accept the word of the writer is not enough. The case of Kanazawa is a hybrid. The question with him, then, is which is to prevail, sanction or freedom. I have yet to make my mind up. Simplistic notions about freedom, truth, racism and courage do not assist me. In fact, they distract.

We should also reflect upon our assumptions and the press coverage in the case of Dominique Kahn.

Offense, like beauty, is in the eye (or, possibly, the ear) of the beholder. It does not have to be grievous to offend. Not in today’s world. All that needs to happen is that someone perceives offense. (see my comment to Thomas (I think) regarding a politician using the word “niggardly.”)

Should Hitler’s words have been stopped, Andreas? He was a writer who didn’t hedge.

Do you say the consequent atrocities were justifiable in the interests of free speech?

Of course you don’t. So there is a line to be drawn.

In this debate, there is a deafness to the power of the word and its potential for bad as well as good.

I’ll bite the bullet. No, I don’t think we should have stopped Hitler’s words. Yes, once we realized he had intentions as a leader of a nation to use his military to attack another country we had every justification to intervene. Allowing him to speak also gave us plenty of clues to his intentions.

Sure, we could forcefully speak out against his vile characterization of jews and other minorities. But just invading Germany before they actually acted on any of their speech would have been bizarre. It’s not like we KNEW at the time what would happen. Of course, if there is now some case of a military leader telling people he’s going to commit crimes against humanity that may warrant intervention – but it’s not to stop his speech.

Good on yer, Dan.

You say that Hitler’s words didn’t encourage the thugs he gathered round him? That those thugs didn’t gain power ostensibly through democratic process? That no-one saw what was happening before ever there was war? That Germany was incapable of dealing with the situation internally?

That last would be a gross calumny against the people and culture of Germany, a league ahead of its rivals. That is the puzzle and terrible lesson of the twentieth century: culture alone is no protection against barbarity, whether in a people or in an individual.

That we have really known since antiquity. It is as well we recognise the fact, have constant vigilance and regulate our ways in the hope (perhaps vain) that repetition may be avoided.

I am perfectly willing to concede that we have to be equally alert to those who would rob us of freedom.

@Richard,

You say that Hitler’s words didn’t encourage the thugs he gathered round him? That those thugs didn’t gain power ostensibly through democratic process? That no-one saw what was happening before ever there was war? That Germany was incapable of dealing with the situation internally?

Answers to your questions (in order):

No.

Yes, they did. But that had nothing to do with Hitler’s words beyond what any politician’s would.

Few did and they were not listened to. Instead, they listened to Chamberlain and Lindbergh.

Yes, it is clear that Germany was incapable of dealing with the situation internally.

Douglas.

1. From his earliest appearance on the political scene, Hitler gained concessions as a result of his utterances.

2. There were others whose views were, as now, just as extreme but who did not gain the following. If Hitler had been silenced, the rest is unlikely to have followed.

3. True, few didsee what was happening. Fewer still are alert to possible signs today. Do you favour a blanket permissiveness irrespective of inanities and dangers?

4. If Germany was incapable of dealing with the situation internally despite its culture, then we must ask why, lest others go the same way. Maybe it was poverty, loss of dignity after 1918, irrational nationalism, indignation at economic chaos – all pandered to by Hitler – but more importantly a failure by the well-intentioned to distinguish freedom and licence at an early stage.

@Richard

If Hitler had been silenced, the rest is unlikely to have followed.

Perhaps, but what silencing methods exactly would you suggest? More importantly—the $64,000 question—who, in your view, should have the power to decide who is to be silenced?

You’re a lawyer. It would be interesting if you could draft a silencing law for us and post it below, which will set forth exactly (a) who has to power to silence, (b) on account of what verbal offenses silencing may be used, and (c) the permissible methods of such silencing.

@Richard

1. Yes. He also went to jail at one point on his way to power. He then figured out a way to use the system to gain power (and then used that power to squash opposition).

2. See #1

3. Yes, I do.

4. We cannot know what would have happened. Perhaps something worse. Speculation is always tinged with bias.

I struggle with your interpretation of the world, Douglas. You reckon words do not influence events, people are not influenced by others, positions can be taken without justification and there is no interpretation or foresight, only speculation.

I may never be able to absorb this.

@Richard

I do not “reckon words do not influence events, people are not influenced by others, positions can be taken without justification and there is no interpretation or foresight, only speculation.”

I strongly believe that words mean things, that people are influenced by them, and influenced by others (gifted orators or close friends or even articulate and charming strangers), positions can be taken both with and without justification, and that there is interpretation and foresight.

On the words being influential, I strongly believe that and that is why I see the less restriction on them, the better. Those who “speak truth to power” are often the opposition, politically speaking. Anyone in power, no matter how they got there, would rather have no opposition or be able to control what it says, where it can say it, and when it can say it. I do not like the idea that those in power get to pick and choose who gets to say what. I see that as much more dangerous than letting crackpots speak.

Interpretation of possible futures is speculation. One cannot know what might have happened if certain events had not occurred. Had slavery been outlawed throughout the states prior to the Civil War, would we still have had that civil war? Slavery was only one of several issues involved and was a very important one but eliminating it as a factor does not automatically rule out a civil war nor does it mean there would have been no other equally dangerous schism in the U.S. Unless one has a bias about that subject.

Foresight… and interesting concept. Let’s suppose you saw Hitler in 1930 as a threat that could trigger an attempted genocide, Germany re-emerging as a military power, and a war greater than the Great War. Your name might be Winston Churchill. You would find yourself ignored until much later.

Let’s suppose you lived in the U.S. in 1930 and you saw war with Germany as a great possibility if Hitler gained power. What could you do? The nation was strongly isolationist and had no desire to get involved in another European war. We did see the Japanese expansionism as a threat and many predicted war with them. We tried to take steps to restrain them but these steps may have made things worse, may have forced things to a head. Those who suggested those steps undoubtedly had foresight concerning a war but that doesn’t mean they had to be right nor did it mean the steps taken based on that foresight were the best ones.

Put another way, I have never met anyone who could predict the future, why would I believe that someone could accurately predict an alternate one?

I suspect that your difficulty in absorbing this is partly (maybe strongly is a better word) cultural in nature. You are a product of your culture as I am of mine.

On the free speech issue, let me offer one more example:

http://www.kansaspress.ku.edu/strwhe.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Socialist_Party_of_America_v._Village_of_Skokie

A Jewish attorney, working for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), defended the right of the American Nazi Party to stage a march in Skokie, Illinois, in 1977. Skokie was predominantly Jewish and many were former Nazi death camp survivors or had relatives who were or who perished in those camps.

Evelyn Beatrice Hall said, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,” (wrongly attributed to Voltaire). This is the heart of Freedom of Speech.

@ Richard, sorry for the delay, I’ve been busy working. Also, unfortunately, I haven’t got the chance to read the rest of the comments thread so I hope I’m not making any redundant points. I’ll just stick to responding to what you said to me.

“You say that Hitler’s words didn’t encourage the thugs he gathered round him?”

No, I didn’t. In fact, I actually didn’t say any of the things you went on to ask if I said.

You asked previously if we should have stopped “Hitler’s words.” Again, I repeat that no it wasn’t a moral imperative to stop Hitler’s words. Once his words started turning into intentions to act, the case grows stronger for intervention. Once action begins, the case for intervention may have been iron-clad. Notice this doesn’t imply that Hitler’s words didn’t spark or reveal those intentions or actions. But if Germany went on spreading libel about the nature of jews to no tangible effect (in this hypothetical, maybe the US and some Europeans spread effective counter-messages) there would have been no good reason to start a war.

Again, we’re looking at this historical situation through hindsight. If you’re asking if we should have stopped hitler… well, obviously, yes. But, as I asked before, if there is a leader of a country spreading vile propaganda to his citizens, do you really favor targeted killing or full-scale war without any evidence of capacity and intention for him to commit crimes against humanity? Just to stop his words? Obviously words may have strong negative consequences, but so might a full-scale war or an assassination (google archduke of ferdinand). I’m not arguing that words don’t have consequences. I’m just arguing that while weighing the entire scope of consequences from action it doesn’t make much sense to commit to such a serious step as “stopping” someone’s words. Caution: History in the rearview may appear clearer than it is.

I didn’t say I would go to war to stop words, Dan, although I’ll have to consider it now. 🙂

Didn’t you ask, “Should Hitler’s words have been stopped”? I answered, no, assuming by “stop” you mean by force. So that’s either assassination or war, right? If you just mean convince him to stop talking by rhetorical persuasion or something similar, I’m not sure what you were trying to get at with that question. Does anyone think that literally nothing should have been done about Hitler’s words? Is that a position that needs refutation among readers of The Hannibal Blog?

In 1804 Abigail Adams and Thomas Jefferson exchanged letters on whether the federal government had the right to imprison those who “slandered” congress or the president. The exchange was prompted by President Jefferson pardoning a man who had been jailed under the Sedition Act during John Adams’s term, specifically for his criticisms of Adams:

Abigail Adams to Thomas Jefferson, Quincy, 1 July, 1804

One of the first acts of your administration was to liberate a wretch, who was suffering the just punishment of his crimes for publishing the basest libel, the lowest and vilest slander which malice could invent or calumny exhibit, against the character and reputation of your predecessor; of him, for whom you professed a friendship and esteem, and whom you certainly knew incapable of such complicated baseness.

Abigail Adams to Thomas Jefferson, Quincy, 18 August, 1804

That some restraint should be laid upon the assassin who stabs reputation, all civilized nations have assented to. In no country have calumny, falsehood and reviling stalked abroad more licentiously than in this. No political character has been secure from its attacks ; no reputation so fair as not to be wounded by it, until truth and falsehood lie in one undistinguished heap. If there is no check to be resorted to in the laws of the land, and no reparation to be made to the injured, will not man become the judge and avenger of his own wrongs, and, as in a late instance, the sword and pistol decide the contest? All christian and social virtues will be banished the land. All that makes life desirable and softens the ferocious passions of man will assume a savage deportment, and like Cain of old, every man’s hand will be against his neighbor.

Abigail Adams to Thomas Jefferson, Quincy, 25 October, 1804

I cannot accord with you in opinion that the Constitution ever meant to withhold from the National Government the power of self-defence; or that it could be considered an infringement of the Liberty of the Press, to punish the licentiousness of it.

——————————–

Thomas Jefferson’s reply:

Thomas Jefferson to Abigail Adams, July 22, 1804

I discharged every person under punishment or prosecution under the Sedition Law, because I considered, and now consider, that law to be a nullity as absolute and palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image.

Jefferson explains his philosophy of free speech here:

Thomas Jefferson to Judge John Tyler, Washington, June 28, 1804

I may err in my measures, but never shall deflect from the intention to fortify the public liberty by every possible means, and to put it out of the power of the few to riot on the labors of the many. No experiment can be more interesting than that we are now trying, and which we trust will end in establishing the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth. Our first object should therefore be, to leave open to him all the avenues to truth. The most effectual hitherto found, is the freedom of the press. It is therefore, the first shut up by those who fear the investigation of their actions. The firmness with which the people have withstood the late abuses of the press, the discernment they have manifested between truth and falsehood, show that they may safely be trusted to hear everything true and false, and to form a correct judgment between them.

——————————–

And in case you are wondering what John Adams contributed to his wife’s letters to Jefferson:

John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, Quincy, 19 November, 1804.

The whole of this correspondence was begun and conducted without my knowledge or suspicion. Last evening and this morning, at the desire of Mrs. Adams, I read the whole. I have no remarks to make upon it, at this time and in this place.

http://www.crf-usa.org/america-responds-to-terrorism/the-alien-and-sedition-acts.html

Click to access Sedition_Act_cases.pdf

The First Amendment

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

All reasonable people join Jefferson in spirit, Jim M. It is in the particular he may err in his measures, as he himself anticipates.

His talk of golden images is a little outdated, but was probably highly relevant at the time. All things have to be judged in their context.

[It is all very disconcerting. You are named as if I am addressing one of my sons!]

@Jim M.,

I have never felt more Jeffersonian.

If Germany, in 1920 or thereabouts, had had hate speech laws of the kind that most western countries now have, would World War 2 have happened?

It would have been less likely, Philippe, and that is sufficient justification.

Hi, Cyberquill.

I would silence by law. Framing law is a matter for the legislature and its enforcement a matter for the courts.

I am still reflecting on Kawazama’s case and so am not in a position to suggest a law. It is possible to do this, I am sure, and strike the correct balance. There are cleverer lawyers than me about that you could ask.

Richard

Since words may influence events and people may be influenced by them it is our duty to examine the question of permissiveness as it relates to speech and consider whether, in the light of past experiences, it is better or worse for humanity as a whole that rare and extreme statements have an undue effect.

In England, we have our recent example of long-lasting hospitality and tolerance of Islamic extremist orators to ponder, their influence upon Islamic youth and the global consequences.

We limit peoples’ freedom to ignore property rights, move across the world, cause physical injury or damage, defraud others or to break promises and so on. Why should our words occupy a special privileged position?

The true difficulty lies in defining the limits to free speech, as Cyberquill shrewdly recognises, and we must pause long and hard before we do so. The freedom is a precious one and when in doubt we should give precedence to it. I do understand the concerns and in my opinion current limitations in England are too wide (particularly libel laws, and now privacy laws), poorly conceived and drawn, based on emotional response rather than reason and do not adequately find their targets. US citizens should be wary of basing their conclusions on an emotional defence of the constitution.

The limits should be defined by the criminal law and not rely upon private suit. It is difficult to work out whether reckless, if learned, naivety of the kind exhibited by Kawazama should be proscribed

Andreas,

you shifted the debate away from the Kawazama issue too soon. You brought in questions of individual conscience, courage and honesty in the speaking of our minds and drew the emphasis away from judging others’ words to judging our own. The shift is relevant, of course, but you confused the line of argument.

Douglas,

It is not possible for me to comment on the Skokie case as presented by the book you cite since I have not read it nor is it possible to reach any conclusion from the brief article in Wikipedia. Suffice it to say that the success of liberal morality may have had less to do with free speech and more to do with the raising of the conscience and consciousness of decent people as a result of WW2.

To suppose these issues, which concern us all, and the attitude to them turn on cultural differences is untenable and evidence, I regret, of US isolationism.

Maybe you and I are using “speculation” in different senses. I had assumed that you meant it in the sense of a gamble rather than a reasoned review of possible causes and effects, It is possible to learn from the past and we should endeavour to do so.

@Richard

It is not possible for me to comment on the Skokie case as presented by the book you cite since I have not read it nor is it possible to reach any conclusion from the brief article in Wikipedia.

We former colonists of the Crown have developed the ability to form opinions on most anything without much knowledge at all, much less in-depth knowledge. It is our heritage, I suppose, gained from from wresting control away from a sovereign to become (at least in our own minds) our own individual sovereigns. I cannot explain individual liberty and freedom to one who views life from the perspective of a subject to an autocratic government. You may not actually do this, of course, or believe you do not in any case. It is how I see you, not how you may see yourself.

Said plainly, we have different cultural histories since 1776. The fact that we had no mortal enemies of any real consequence within striking distance (such as the width of the English Channel… say, do the French want to call it the “French Channel?”) allowed us the luxury of exploring isolationism for a long period. Personal isolationism is also a part of our cultural heritage, an offshoot of our concept of individual liberty. That concept, by the way, sprang from our British heritage and was expanded by the fact that we had so much open territory, we could leave all vestiges of social order and actually be individually autonomous, banding together only as circumstances required.

Speculation is defined neatly in this way:

a. Contemplation or consideration of a subject; meditation.

b. A conclusion, opinion, or theory reached by conjecture.

From: http://www.thefreedictionary.com/speculation

I see it as taking existing facts (historical record) and inserting personal biases to form an opinion of a possible future. This is in the context of predicting what an alternative future might have brought. It is of little use beyond revealing our personal biases are. For instance, if we never came across each other, would either of us ever have a discussion about these things? We could speculate that (a) it would be unlikely due to the clash between our two personal points of view or (b) likely due to our personal points of view conflicting with others. May as well flip a coin,it is just as predictable.

Suppressing Hitler in the 20’s or early 30’s might have averted genocide and WWII. Or it might have given rise to a smarter “Hitler” who succeeded in his genocidal policies and waged a war of conquest more wisely. One can never know.

Tell me, sir, are you a solicitor or a barrister?

A solicitor, sir.

You know, Douglas, actually there’s only a hair’s breadth between us.

“England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

–George Bernard Shaw

While we talk glibly here of freedom to do this, or that or nothing, how many political prisoners have suffered torture or solitary confinement, whose only wish is to see the blueness of the sky or simply to be?

Let those to whom freedom is a right and not a privilege consider that. It may one day happen to us, whatever the law may say.

How many political prisoners have suffered torture or solitary confinement because they merely spoke their minds and tried to resist the State? They would certainly have been better off if they had not voiced those opinions, at least in terms of imprisonment and punishment for daring to offer an alternative to the status quo. But these political prisoners found themselves in their predicaments because they chose to exercise a right that the State did not grant to anyone. A right they saw as more important than their own safety. They stood before the sovereign ruler rather than kneel in supplication.

You live in an ideal and privileged world, Douglas, but I do not blame you for that or for highlighting the importance of courage. In reality, however, there are limits to what the law can achieve and those limits are well short of justice.

Yes, Richard, I think I do live in an ideal and privileged world… or, rather, country. I know these things I believe in and take for granted are not the “norm” in the world outside our national boundaries. I consider myself quite fortunate to have been born here.

there are limits to what the law can achieve and those limits are well short of justice.

This is how we differ. I think laws have nothing to do with this particular right. Laws serve to restrict the freedoms of individuals. They exist to restrain the citizens of a society. This is a universal concept and practice, We, here in your former colonies, did not pass a law granting freedom of speech when we wrote our Constitution. Instead, we wrote an amendment to that document which affirmed the right existed and restrained the government from interfering with it. That may seem a matter of semantics to you. And, indeed, I believe this right has been infringed upon by both Congress and the courts from time to time. Yet, it still exists.

The concept which I think is the hardest for non-Americans to grasp is that governments are not to be trusted to grant rights or protect them. It is a concept upon which this nation was founded. We clearly did not trust the Crown.

What Andreas wrote about in this article revolves around the concept of external, non-legislated, restrictions of speech (or, in this case, writing). Writers can (and do) practice a form of self-censorship out of courtesy or out of fear of offending others. You and I have been talking about the fear of the state imposing punishment. I think there is a huge difference between the two but both restrict the free exchange of ideas.

One question I think writers should ask themselves before writing is whether they are censoring themselves out of courtesy or out of fear of social reprisal (or, perhaps, fear of their bosses).

Do I use words which offend because I want to offend or because they best express a concept? It’s a delicate balance.

I am befuddled, but happy.

PS

I wonder why, I’m not kidding.

You are in love?

Enter now our brilliant star,

Who has read our posts from afar.

He says he’s befuddled

But he’s not really muddled

He’s in love, is our MoR.

It is interesting to imagine the colonial powers of the early 20th-century — Germany, France, Britain — restricting racist speech, when such speech formed such a integral part of the intellectual underpinnings of colonialism. The content of such works as Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden” specifically illustrates a weakness in transporting Europe’s modern anti-hate speech laws back, say, to 1900-1930. The colonialist was frequently not motivated by hatred at all, but by a self-serving condescension, whereas this condescension often generated genuine hatred in return in the minds of their colonial subjects. In light of this, who in the colonial era would have been more likely to be prosecuted under these anti-hate speech laws: the colonialist, who merely expressed racial condescension, or their colonial subjects who expressed their hatred in return?

This stanza of Kipling’s

Take up the White Man’s burden—

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard—

underscores how often it has been the disenfranchised whose speech has been deemed hateful and judged needful of regulation by those who see themselves as intellectually and morally superior. In establishing a law to suppress the public registration of grievances judged hateful by some, Europe has, therefore, established a dangerous precedent.

These risks are compounded by the ways such laws can be selectively drafted and enforced, and the insidious ways such laws can be manipulated by cranks seeking cheap publicity and the status of a martyr.

In any case the government should not impose a requirement of civility or sense on those who debate, as it is the process of debate itself that is needed to determine who is civil and what is sensible.

I have decided not to issue a decree restricting the likes of Kawasama. Instead, I shall bear in mind that he abuses the widespread but misguided belief among my subjects that there should be absolute and unfettered freedom of speech and peddles irresponsible half truths without considering the consequences. May I add that under a less liberal ruler he might threaten the very freedom which those subjects so so sincerely and innocently espouse.

OK, everybody, time for a sanity check:

Hands up, who has heard of “Godwin’s Law”?

It states: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1 (100%).”

Oh, and it’s meant to be humorous. But we have just risen (descended?) to it.

Honestly, here is a post about good and bad writing, about fear when typing your emails, or corporate memos, or the novel you’re dreaming about, about people like Eliot Brockner or me, about ordinary writing minions in the 21st century, and you are discussing…. Hitler?

I mean, really. I say “political correctness > bad writing” and you guys worry about genocide?

When people get carried away like this, there is always the risk of missing something profound, which is the actual subject of the discussion thus distorted: In this case, fear (itty-bitty, quotidien, daily-fare fear) and its effect on verbal expression.

If you really don’t know what Orwell was talking about, or what I’m talking about, consider yourself lucky: It means you’ve only read Tolstoy and Hemingway, not the PDFs cluttering my desktop.

Now, I didn’t think it would be necessary, but clearly it is. I will write a new post with EXAMPLES of bad writing, just so that we can all get on the same page again….

“…….there is always the risk of missing something profound, which is the actual subject of the discussion thus distorted: In this case, fear………..and its effect on verbal expression……..”

Perhaps the somewhat tepid interest among the commenters in the topic of fear and its effect on expression, whether verbal or written, is that today we’ve never been freer to say and write what we like, at least in the western democracies. And the opportunities to write, and to have what one writes, read by many, have never been greater.

So we are left with the time-honoured fears to full public self-expression – the fear of baring the soul, and the fear of being criticised or ridiculed.

Since these fears have always, do now, and always will, inhibit writers other than those who are the most intrepid, any discussion about fear in writing is ultimately futile.

My dear Andreas, we “just(?)” risen to Godwin’s Law? It has been several days since the Evil One was mentioned. But you are correct, we wandered far afield of the actual subject. Though I think we enjoyed the journey.

HA!

triple fist bump for your last comment, Andreas. you beat me to 1984! synchronicity. it was the first book that came to mind when i read your blog entry.

(although i’ll opt out of opining about “political correctness > bad writing”)

sometimes, however as jenny states about blogging… is blogging a “platform for writing or a mechanism for social contact”…?

your readers don’t always engage because they want to stay on topic.

sometimes, we simply want to vent or are lonely or find an internet debate less threatening/frightening than what we must wake up and face-to-face.

wise jenny… “”At least in this regard, the social contact/platform for writing duality of blogging is not contradictory”.

just to be ornery – if hitler had succeeded wouldn’t we be living in the anti-utopia of 1984?

@Andreas, agreed. I knew I shouldn’t have bit Godwin’s Brass Hollow Point. I plead guilty to engaging in the discussion once it was brought up.

Sorry – what is the punishment? 🙂

As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1 (100%).

@Andreas & Richard

This very tendency to see the Nazis lurking around every corner is precisely the problem when it comes to silencing voices as Richard appears to suggest. Obviously and ideally, any fascist movement ought to be nipped in the bud before it can gain serious traction. In practice, alas, this means that voices would be subject to silencing even if they don’t sound overtly heinous and genocidal, namely by using the popular rationale that “covert” hatred is even more treacherous than overt hatred, according to which rationale the most dangerous folks are the slick ones who forgo sledgehammer-type speech in favor of dropping cleverly concealed hints regarding what they’re truly up to, and hence it is of particular importance to stop those in their tracks.

One thing is for sure: silencing no one is the polar opposite of Nazi rule.

I’m sorry—what was the original topic again? Something about PDFs?

Thank you, Cyberquill, You say all I wanted to say, and more, but eloquently, comprehensively and intelligently.

I would only add that Hitler comes up so much because his rise is a continuing puzzle and focuses attention upon and is apposite to (and confuses) today’s most important issues from the occasional to the every-day.

The danger is in neglecting this ugly side of ourselves and that is why we need freedom of speech. The opposite danger is trivialising and numbing that freedom, and the perception of it, on inconsequential matters so as to give the enemies of freedom a voice, particularly those who seek to get their way by instilling fear.

I am persuaded. There should be no restrictive law, but at the same time we should not praise those who simply have a special interest and an axe to grind.

To be sure, political correctness must bear responsibility for a substantial amount of bad writing; however, the role of political correctness notwithstanding, this writer believes that the fear of sounding insufficiently educated, has the capacity, in its own right and not infrequently, to convert perfectly acceptable English sentences into arguably turgid prose.

Peer pressure is not limited to the schoolyard, I suppose. If I get your drift.

Phew! You don’t mince your words do you, jenny.

Richard,

I should know the symptoms: I’m one who has the disease.

You are down today, jenny. What can I do to cheer you up?

“…….the fear of sounding insufficiently educated, has the capacity, in its own right and not infrequently, to convert perfectly acceptable English sentences into arguably turgid prose…….”

Yew is speakin’ thuh truth here, Jenny. Yew sure am. ‘Cause ah don’ have much edjcation mahself, an’ ’cause ah do have this here pro-pens-ity ter write in “turgid prose”, ah am goin’ ter write from now awn in mah own yewneek down-home way.

What yew said, Jenny, is uh ver’tible Road Ter Damascus ‘sperience fer me.

@Jenny:

“… this writer believes that the fear of sounding insufficiently educated, has the capacity, in its own right and not infrequently, to convert perfectly acceptable English sentences into arguably turgid prose…”

Bravo and Amen, Jenny. That’s my point exactly.

@dafna:

“…sometimes, we simply want to vent or are lonely or find an internet debate less threatening/frightening than what we must wake up and face-to-face….”

Totally understood, eagerly encouraged. Thank you for reminding me, dafna. Everybody should vent as they please. (But I can still come in and ask “Huh?” occasionally, can’t I? ;))

@Richard:

“Sorry – what is the punishment?”:

The punishment is that you and all participants in the debate must REWRITE Mein Kampf to make it perfectly politically correct, in an Orwellian way.