American history moves in various cycles. For example:

- isolationist ↔ interventionist (in foreign policy)

- prudish/puritan ↔ permissive/liberal (sex)

- progressive ↔ conservative (attitudes toward change)

But perhaps the most striking and consequential cycle is the one between elitism and populism.

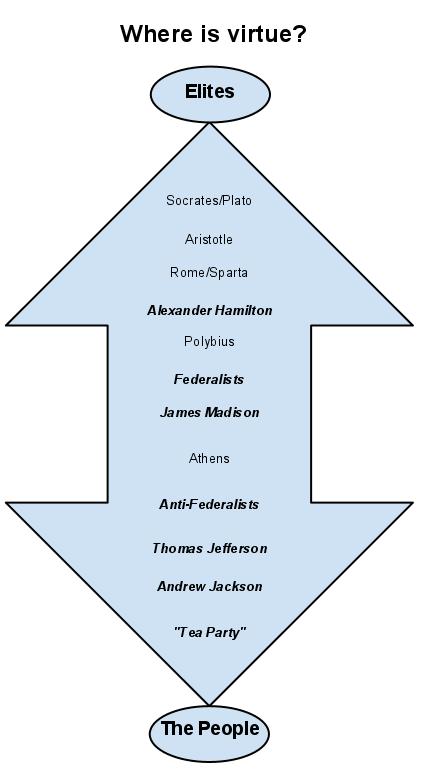

The question here is about virtue. Who is most likely to be virtuous/corruptible? The common people, or the elites?

This question has an ancient pedigree. The answer a society gives at any given time in effect determines the kind of democracy it will practice and the kind of institutions it will build: It will shift power (or pretend to shift power) to the pole it considers more capable of virtue.

I’ll say more about all this in future posts (especially in response to a great biography of Andrew Jackson I just finished reading). But for now I just wanted to amuse myself with another little diagram. As ever, I’m not taking it too seriously, just trying to order my thoughts and invite yours.

Below, I’ve placed some of the figures that have appeared here on The Hannibal Blog over the past two years (each one has a Tag, or you can search for his name) along a spectrum.

Classical thinkers are in normal font, American ones in bold italics.

(Notice the centrality of James Madison, the primary architect of the Constitution. His answer was, in effect, to be agnostic on the question. Therein lies his genius and the strength of the constitution. So he represents the neutral value, 0)

So weigh in. You can also suggest where to place other thinkers, such as John Locke or Montesquieu, or modern pols such as presidential candidates, or foreign politicians.

Which bio of Jackson? I bought and then discarded Jon Meacham’s, I’m afraid, and am reading What Hath God Wrought (broader in scope, on America 1815-1848) instead.

Jefferson is hard to place, because he believed in the yeoman ideal *man* was he an intellectual. The same emphatically cannot be said, of Jackson. I wonder how much time Jefferson spent around common people; the guy founded a university, built his own famous home, and gathered the finest library in the country. He was an ambassador, a prolific writer and a pathbreaking philosopher, and so on. He spent his time in the most civilized parts of America at the time, plus Paris. This doesn’t leave a lot of time for the soldiering, brawling and duelling around the “old Southwest” that was basically most of Jackson’s life.

I’m fascinated by Jefferson, but I’m also always skeptical of an elite intellectual hero of the common man. In this day and age, it is the “anti-elitist” conservatives who extol heartland America but live in DC; the hypocrites who are themselves not devout believers but espouse religion for the virtue of the masses; the ones who made fun of Obama’s musings on arugula and then went across the street for a $30 lunch, and so on. Mitt Romney and his “varmint” gun; Karl Rove the agnostic who mobilized Christians against gays; George W. Bush the Connecticut cowboy… the list really does go on.

“Elite” has really become bleached of meaning except “my political opponents’ loathesome views.” Nobody claims to be elite anymore; people actively run from the label. Actually, I just remembered that I wrote this last year:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/johnson/2010/10/semantics

Jon Meacham’s bio. I loved it. Why did you stop reading?

Re the ironies and contradictions of Jefferson: They are the mirror image of those of Hamilton. I went deep into this in this post.

In effect, the irony is that Hamilton, an illegitimate child and quasi-orphan from the Caribbean, worked himself up through American society with sheer grit and talent to become…. a perceived champion of the “aristocracy.”

By contrast, Jefferson, a slave-owning southern gentleman on a big estate who lived as an aristocrat in Paris became perceived as …. the champion of the common folk (ie, white men) as distinct from the corrupt elites (hence the choice of “republicanism” as the name for his faction, with the implication that the Hamiltonians were “monarchists”).

So allow me to clarify something about the diagram above:

It’s not the whence but the whither that I plotted. (Ie, hypocrisy/irony is assumed.)

Thus Socrates came from a humble background but came to advocate government by the (philosophical) elite. George W Bush might have come from blue-blooded Kennebunkport/Connecticut stock but posed as the “common man” from West Texas when running against the “aristocratic” kerry. Etc Etc.

So the diagram is where, according to rhetoric or actual policy, a person or culture places its trust in terms of decision-making: the people (the “mob”, for the other side) or the elite (the “elite” again, for the other side).

Fantastic post about the plasticity of “elite”. What an awful corruption of the word here in the US. Sort of like the corruption of “liberal”.

Damn, meant to say Jefferson believed in the yeoman ideal, but *man* was he an intellectual (the ‘man’ being an intensifier, not a reference to an actual man.)

Does the “Tea Party” really belong in “The People” section of this continuum?

While it champions “The People”, it wants to shrink government drastically. This would favour the rich at the expense of the non-rich, in the way the drastic shrinking of government anywhere inevitably does.

Since most of “The People” belong to the non-rich, should not the “Tea Party” be in “Elites” part of this continuum?

As to the other people and groups in this diagram, did any have philosophies, which, if widely adopted, would also have had consequences opposite to what their espousers intended?

Judging from the footage I’ve seen, most folks at Tea Party rallies don’t exactly strike me as members of wealthy elites. So I suspect a more complex set of motives may be in play than merely the desire to protect the fortunes of the super-rich. I doubt you’ll find many billionaires in jeans and T-shirts walking around carrying hand-written signs at Tea Party demonstrations.

And the Tea Party probably doesn’t want to shrink government per se but shrink the federal government in favor of empowering state governments. This inevitably entails a more narrow constitutional construction, i.e., the notion that the Constitution covers less ground and that hence more issues are subject to popular vote, which means more power to the people at the state level.

Also keep in mind that most countries with strong federal governments that are successful at keeping to a minimum the wealth disparity between the rich and the poor aren’t the size of the U.S. but rather the size of individual U.S. states. (At least I’m not aware of a centrally-governed 300-million-plus-country that successfully functions like Denmark or Switzerland in terms of securing a decent standard of living for all.)

Having grown up in a quasi-socialistic country of eight million people—the same number than live in New York City alone—with a relatively high standard of living for most, I also feel that smaller governmental units (like Austria or individual U.S. states) may be in a better position to care for its citizenry than a central behemoth government with hundreds of millions of people in its charge.

And when I argue in favor of less federal U.S. government, I hardly do so in order to protect some wealthy elite I’ll never be part of at the expense of paupers like myself. This idea that everyone who favors less federal government is primarily concerned with protecting the rich is ludicrous.

Philippe, same clarification as for Lane, above:

I’m interested in where the group (in this case, the Tea Party) places credibility, authority etc, not in the actual effect of the policies it may espouse (which can be self-defeating).

the Tea Party thus falls very much into the Jacksonian tradition (I will devote a separate post to this soon).

It started (indeed, never progressed beyond) a grassroots, populist outcry against perceived elites and establishements (even within the GOP. Witness what happened to Utah’s former senator Bennett).

The core tenet, to its faithul, is that the pure, reasonable, sane, decent common people must rise up in anger at the corrupted elites who want to steal the country away.

Labels rarely identify any politician accurately. Politicians are more chameleon in nature, they try to be whatever the people they are speaking to want. Call it “political pragmatism.”

But I think I will stay out of this one.

That’s so obvious it hardly needs pointing out. Andrew Jackson, for instance, was a walking bundle of contradictions. But that doesn’t mean that labels cannot be useful for organizing one’s understanding. For a start, politicians do nothing but label — one another.

Fascinating area for exploration but I think the diagram may need to be tweaked. At a mininum it needs to be a matrix and possibly a three dimensional one. The complication arises from the issues that Lane and Phillipe raise–first with respect to definition of terms and second with respect to fundamental ideology vs. demagoguery.

The problem in my mind arises from trying to create a Procrustean bed out of western political philosophies (i.e., the Greek, Romans and the Founding Fathers) when political movements of the 20th century are based on radical ideologies that are not based on those philosophies and indeed are either ignorant of them or actively wish to destroy them. I think this is related to Philipe’s question about the Tea Party. Do theyhave an underlying philosophy behind their ideological rants and sound bites that questions any of the tenets of Western thought regarding systems of government. We might as well ask what was Socrates position on flag burning.

And it’s not just the Tea party. Nazism (sorry to violate Godwin’s law by invoking the Nazis so quickly) is another example. And Communism under Stalin as well. Were these logical extensions of the tradition of thinking about a continuum between the elite and masses or radical reactions to a set of circumstances. End of ramble.

Ah, Mr Matrix, as I recall. 😉

I did put “matrix’ in the title. But think of this as warm-up practice for just one axis (Y, or X, or Z or whatever). One could matricize it by combining it with, say, this diagram on another axis, and perhaps with Time for an animated sphere and so forth.

But that’s not where I was going here.

You can indeed separate ideology (left/right, say) from style or worldview (elitist/populist, say).

And I would not try to stretch it beyond “republics/democracies”. So yes, the Chinese Communists today, for instance, are inherently “Hamiltonian/Socratic” in believing that the Chinese masses cannot be trusted to run the country. But that would be stretching things toa ridiculous degree. I’m interested in political styles in countries where people actually have a choice.

This is more nuanced than might appear. For instance, what is Singapore? I would included it here, and I would call it a modern Sparta. Hong Kong: a tiny Hamiltonian Rome. France: Up there in the Aristotelian area.

By contrast: California, Arizona, Oregon, Colorado: Down there with Jackson (ie, fond of direct democracy over representative democracy).

Sarah Palin: Ultra Jacksonian (and again: that says nothing about whether her “policies” would even be coherent, merely about where she pitches her appeal and draws her strength from).

Etc

Yes, your clarification about whence vs whither puts a different spin (and more logical focus). I will think upon a matrix. I love the Singapore as Sparta analogy. Where would you put Japan?

Japan: More Spartan than Athenian, more Hamiltonian than Jeffersonian … until Fukushima.

I expect that you’ll see a shift away from “elites” and toward “the people”. Just a guess, though.

@Cyberquill – “………most countries with strong federal governments that are successful at keeping to a minimum the wealth disparity between the rich and the poor aren’t the size of the U.S……….”

The large size of the US didn’t prevent it from having, between 1941 and 1979, an income inequality between rich and poor that was little over half of what that inequality is today. Hence the size of the US may have little to do with this problem.

“……..the Tea Party……doesn’t want to shrink government per se but shrink the federal government in favor of empowering state governments……….”

If true, then I assume the Tea Party would accept a corresponding expansion of state and local government, which would have to happen if they took over certain responsibilities from the federal government. Hence the Tea Party wouldn’t necessarily be in favour of the shrinkage of overall government, only the shrinkage of the federal one.

If true, then Andreas may indeed not have been incorrect in putting the “Tea Party” in “The People” section of his diagram.

“……..This idea that everyone who favors less federal government is primarily concerned with protecting the rich is ludicrous…….”

While this may conceivably apply to the ordinary members of the Tea Party, does it apply to its leaders? Consider their recent furious opposition – at the risk of causing a global economic collapse – to the very idea of taxing the rich just a bit more so that the federal deficit might more realistically be reduced.

Well, if taxing the rich just a little bit more actually works to reduce the federal deficit, that’s fine. The question is, whether raising taxes on the rich even further will result in more or less money flowing into the Treasury. (For instance, to circumvent the 35% corporate tax in the U.S., many corporations simply move abroad. Then they pay 15% corporate tax to the Swiss treasury, and the U.S. gets nothing. If the U.S. corporate tax were lower, many corporations would probably skip the hassle of moving overseas in the first place. Thus, exorbitant taxation may actually drive the rich out of the country and potential tax revenue is lost. Perhaps I’m mistaken, but that’s nonetheless my sincere concern when it comes to raising taxes, namely that as per the law of unintended consequences, LESS money may be coming in that way. Personally, I couldn’t care less how many billions some fat cat gets to keep after taxes. I’ll never be in a class where “taxing the rich” will affect me anyway.)

The large size of the US didn’t prevent it from having, between 1941 and 1979, an income inequality between rich and poor that was little over half of what that inequality is today.

Keep in mind, though, that the U.S. population isn’t exactly shrinking with time. In 1941, it stood at about 135 million. Since then, it has grown by roughly five (!) times the entire population of present-day Canada. (Since 1979, it has grown by roughly twice the entire population of present-day Canada.)

You guys are still debating policy outcomes, not sources of political legitimacy, which is what this post is about.

We’re just trying to order our thoughts.

was madison really agnostic on the question? can anything be inferred by this quote?

“It has been frequently remarked, that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not, of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend, for their political constitutions, on accident and force.” – The Federalist Papers

am i on topic?

Totally on topic, dafna.

But I’m cautious about inferring too much from any single quote of Madison’s. I read deeply into The Federalist Papers (ie, Hamilton, Madison and Jay, in that order, in terms of prolixity) for my recent Special Report on California’s direct democracy. And what came out of Madison’s writings was the holism, or broadness, of his perspective. You can find quotes in which he seems to favor “the people”, others in which he seems to caution against “pure democracy” and against “the people”, others yet in which he cautions against “the passions” of the people, and so forth.

Hence my judgment that he was, in fact, deliberately agnostic on this question. (I am speaking of Madison at the Constitutional Convention and during the writing of the Federalist Papers. I am not speaking of the Madison that became a partisan of Jefferson against Hamilton in later years. Oh, the mystery of the human condition.)

Look at the Constitution that he (not alone, but more than anybody else) conceived (and which now, much amended, seems exotic to us):

– An executive (ie, president) elected by electors (the Electoral College, which actually did the choosing, as an explicit “aristocracy” in terms of access to information and privileged judgment).

– A Senate whose members were chosen by state legislatures, not by voters

– An independent judiciary

You see: layer upon layer of “filters” — or “saucers” to “cool” the hot tea, as Washington wrote to Jefferson in a letter — between “the people’s” will and actual policy.

Madison placed “the people” in the House. Just the House. One half of one of three branches. So 1/6, or 17% of government.

Did he “trust” the executive? Nope. Did he “trust” the aristocracy? Nope. Did he “trust” the people? Nope.

As I’ve posted here before, he took the view of Polybius (whom he had read) and decided that the only appropriate way to preserve a republic such as this fledgling creature (like Rome during the war against Hannibal) was to balance the three elements (monarchy, aristocracy, democracy) so that none could, when (not if) corrupted, undo the whole.

That’s why I put him at neutral (=0)

A genius. Still underrated.

@Andreas – “…….You guys are still debating policy outcomes, not sources of political legitimacy, which is what this post is about………”

I suppose we are, and are therefore going against the spirit of your posting. Straying slightly off topic, though, can sometimes reveal facts of which most people may not be aware, but should be.

For instance the slightly off-topic conversation between Cyberquill and myself, has revealed that the Tea Party isn’t against smaller overall government, and so presumably would support the current levels of overall taxation, since these overall taxes are needed to fund the present levels of overall government.

That the Tea Party isn’t against smaller government as such, or against lower taxes as such, may come as news to many Tea Partyers, and indeed to non Tea Partyers too.

@Cyberquill – “………the U.S. population isn’t exactly shrinking with time. In 1941, it stood at about 135 million. Since then, it has grown by roughly five (!) times the entire population of present-day Canada. (Since 1979, it has grown by roughly twice the entire population of present-day Canada.)………..”

In 1928 – when income inequality in the US was what it is today – there were 120 million Americans. In 1941 – when income inequality had halved – the population grew to 133 million, merely 11% more than in 1920.

Between 1941 and 1979, the numbers of Americans went from 133 million to 227 million, an increase of 71%. However, income inequality remained substantially the same throughout that 38 years.

While the US population from 1979 to today may have grown by twice the current population of Canada, this growth represented only a 32% increase in the numbers of Americans. But, during that time, income inequality doubled, to where it was in 1928, when the population was only 40% of today’s.

It seems, therefore, that there’s little correlation between population size and the degree of income inequality.

“……to circumvent the 35% corporate tax in the U.S., many corporations simply move abroad……..”

This rate of American corporate tax (an average of 39%, actually, when state income taxes are added), while higher than for most other industrialised lands, is only marginally higher (Germany is about the same, Japan slightly higher, Canada slightly lower).

You say “…..many corporations simply move abroad…..”. This is rather vague. How many is “many”? Certainly a lot of companies (and not just American ones) have moved their day-to-day operations abroad to the poorer lands, but on account of the much lower wages there.

In the realm of income taxes, rates on incomes of the American rich are not only substantially lower than rates on the rich in well-nigh all the other industrialised lands, they are at their lowest in the last 50 years.

Might I ask you a simple question?

What, exactly, is “income inequality” and what is its antithesis?

Should we all make the same amount of money (full “income equality”) or is there a certain percentage difference which would be acceptable? And who would decide that?

Ok, that was two questions and neither one is all that simple. But humor me.

(@Andreas, I really did try to refrain)

Ah, inequality. Great topic.Here was my take on it before. Maybe you guys will force me to revisit.

My take on income inequality is that a certain degree of it is acceptable and inevitable (although reasonable people will differ on what exactly that degree is), but when the richest 1% own 80% of a country’s assets (or whatever the exact proportion may be in the U.S.), that’s a problem, and it’s a huge problem, as it indicates a major flaw in the system. After all, the founding idea behind the United States was to get rid of the concept of inherited aristocracy, not to replace a blue-blooded aristocracy by a green-blooded de-facto aristocracy. Either way, a small elite—and not necessarily the best and the brightest—are born into tremendous wealth and power. Not good.

That said, I doubt whether taxing the rich “a little more” will bring about a meaningful reduction in income inequality as we experience it today. The problem seems more complex and fundamental than to be remedied by the federal government simply seizing more assets.

@Cyberquill, I would differ with you on one thing, “After all, the founding idea behind the United States was to get rid of the concept of inherited aristocracy, not to replace a blue-blooded aristocracy by a green-blooded de-facto aristocracy.”

The founding idea, I thought (and think) was something called “equal opportunity”. That is, you are not bound by class restraints. You could be the child of a farm laborer yet you could become a businessman and wealthy, for example. Under the old systems, you were pretty much defined by your birthright. You could be apprenticed to another caste but upward movement was extremely rare, if not impossible. The class restraints were essentially removed.

But it is difficult, in my view, for human nature to eliminate elitism. We still believe in aristocracies; hence the Kennedys (one of my favorite examples) and the infatuation with celebrity (as in Princess Diana, Paris Hilton, the Kardashians, and many sports stars) though that is often tinged with schadenfreude, it seems.

I could be wrong.

I like this baby matrix (baby in that it will grow more axes in the future, if I understood Andreas correctly). I like any graph that creates surprising associations like, for instance, the Tea Party and Maoists. Again, if I’m understanding this correctly, it’s a rhetorical analysis of political thought, which puts Mao Zedong way over on the side of The People. Confucius, on the other hand, was way over on the side of the Elites, and Mao Zedong was wildly anti-Confucian in thought.

I’d put Thomas Hobbes somewhere around Socrates/Plato…. The English monarchy prior to the Norman conquest was a kind of republican monarchy, in that the barons elected their king. I think the same is true of the German kings through the Holy Roman Empire? Still Elitist, but not as much as Hobbes or Plato or Confucius.

I think Hitler proves more tantalizing here than we’re giving him credit for … which is an interesting sentence to type. I admit, I’m not very familiar with his rhetoric, but the Nazi party and its Neo-Nazi descendants try for a kind of Populist Elitism (or Elitist Populism) in that they posit a government by and for the best people. Do they fit on this graph?

A possible y-axis for the graph might be how each group/thinker sought to implement their populism/elitism (Liberal Freedom? Totalitarian Control?). That would put Mao and the Tea Party on opposite ends of The People. Hobbes near Mao but for Elitism … is Madison still in the middle? Rouseau … contra-Hobbes, Liberal Freedom for The People?

GW Bush claimed to be chosen by God for the Presidency, and I wonder if Rick Perry will ultimate make the same claim … a divine right of Presidents? I don’t know … I’m just thinking out loud here….

Whoops … I meant “possible x-axis” since we already have a y-axis…. Damnable typos.

🙂 🙂 🙂

well done!

Well done indeed, Chris. LIke, like, like.

Yes, to hell with “democracies and republics”: Let’s expand this to China. Mao and Confucius are the extreme poles, you’ve made me realize.

Hobbes, however, is more complicated. I was actually considering him when I thought of a proper “matrix” that included not just “where is virtue?” but also “where is corruption?”

Hobbes, as I recall, basically started from the premise that we (Homo Sapiens) are all corrupt, that, when left to our own devices, we will make one another’s lives (life?) “poor, solitary, nasty, brutish and short”.

So I think Hobbes would have answered our question by telling us that the question was wrong. I conjecture:

“It is not ‘where is virtue?’ but ‘where is depravity?’ And the answer is: ‘Tis everywhere. In the nobility, in the peasants, in the king and the cleric…..’

If he’d had a good, long chat with Madison, I think the two might have agreed on the exact same constitution. 😉

😀 Thank you, dafna and Andreas. An intriguing take on Hobbes, Andreas. I admit a growing sympathy with Hobbes’s pessimistic take on humanity, and I think you’re right that he would have inverted your proposed question … I don’t know if he would have agreed with Madison (et al) on the Constitution. They certainly would have had a lot to agree on. I don’t know though … Hobbes rejected the idea of separation of powers, and he was ready to surrender everything to a sovereign. Right before writing this, I spent a curious amount of time staring at the frontispiece to Leviathan. There’s the sovereign, looming over his city, sword and crosier in hand. But if you zoom in, you can see that his torso and arms are completely made of the bodies of other people. Maybe they would have agreed, eventually … maybe if Hobbes hadn’t written during the English Civil War…. It would have had to have been a long conversation, though.

I wonder whilst staring at the above graph if the key to it is the revolutionariness of the thought. Mao, Robespierre, even the Tea Party are heavily founded on a revolutionary ideal and make strong appeals to The People. There is at least a correlation. It’s interesting that Madison and Hamilton are not on that side, and that there was a considerable rift in the Founding Fathers regarding the new government. It brings to mind a history professor of mine who argued that the American Revolution wasn’t exactly revolutionary, in the sense of upending the political hierarchy as happened in France or Russia or China. That it may be more appropriately labeled the War for American Political Autonomy, as opposed to the American Revolution. The American Revolution was also exceptional in that it didn’t turn in on itself the way the French, Bolshevik, and Chinese Revolutions eventually did.

Ha ha … forgot to close the link html. Sigh, and the typos continue….

Two comments on an interesting question and discussion. First, since the Tea Party is the only contemporary actor evaluated as well as the polemical subject du jour, it merits pointing out the slipperiness of that moniker. I don’t know if you all have the following idea in mind: 300,000 mostly white male conservative Republican grass-roots activists working on issue and campaign specific goals CUM high-net worth-funded anti-tax corporate lobbies. Beyond that, we can’t pinpoint the Tea Party movement as actor except to say i) it is distinct from much broader Tea Party sentiment and ii) it is riven with a basic split between populism and elitist pro-wealth funding and legislative agenda. On the latter, foreign policy shows a distinct split between i) neo-Jacksonian “don’t tread on me” bring our boys home from foreign ratholes isolationism favored from libertarian Pauls to cultural conservative Huckabee and ii) traditional Romney/Reagan-style neo-Hamiltonian pro-military globalism. But trying to pin down a particular Tea Party ideology means less than identifying and predicting the ultimate influence of its self-appointed patriotic champions upon the US policy debate and outcomes.

Second and more broadly, on the notion of legitimacy as VIRTUE – I see virtue as a classical republican and thus an essentially elitist concept, reminiscent of the 1780’s and 1790s as opposed to the later decades and great bulk of American history. It is refreshingly dischordant to have Andreas and other earnest thinkers posting on this train about virtue – yet sadly so detached from US society today, steeped as it is in irony, shallow cleverness, and cynicism. In reality, in the public mind today, virtue is a joke – no one would even understand that. The fact of virtue as a joke – one that we all know that too well – raises the question of whence legitimacy.

The disjunction between virtue and power can likely explain much of the discontent and the absence of rationality in American politics. At the same time, and on the other hand, I would say that there remains a major source of legitimacy in the process of democratic politics. Much more mundane than populist stemwinding or elitist visions and designs, the routine process of a highly pluralistic rule-based system sustains a good measure of legitimacy. So perhaps the glass is half full since, in a healthy republic, an assessment of one’s corruption or legitimacy ought to accord not with one’s status but with one’s record of behavior. So I find the success of Rand Paul and the conviction of Bernie Madoff refreshing. Whether or which is more elitist or populist, each is enjoying just desserts in proportion to his virtue.

Hurrah, Dr. Lieber!!

Yes, good points. It was cheeky to include only the Tea Party among modern contestants. To wit: I did NOT have in mind the “aristocratic” Koch brothers (who are funding the TP behind the scenes). I had in mind the “populist” hordes and the politicians who are claiming to speak to and for them.

“The fact of virtue as a joke…”

Virtue really is a joke today. yes. Originally from Latin ‘vir’, man, meaning manliness — as in stalwart and brave patriotism, as of a Fabius against a Hannibal — it then became ‘chastity’ for a while and then a syllabus item in History and Philosophy 101 classes.

But I was struck in my readings how often all the people mentioned in the diagram used the word in their own writings. I’ll provide some quotes in my future posts on Andrew Jackson. In the Federalist-Anti-Federalist debates, virtue was THE issue.

So I’m wondering whether we’ve just given it a new name. Such as: legitimacy. Or (less ugly) trust. Or even ‘common sense’.

An earlier comment went into the ozone so at the risk of repetition I’ll post again.

I may be demonstrating a keen grasp of the obvious here but it occurs to me that one of the problems we are having is a sort of variation on Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Today when we talk about Socrates or Aristotle or Hamilton or Jefferson we look at their fundamental philosophies which have been boiled down to their essence. We do not discuss Hamilton vs. Jefferson in terms of how it might affect our slave holdings or affect our trade with France, etc., which were the burning issues of the day. (and those were some of the issues one’s virtue might be called into question on).

Today when we discuss political polarities and the TP comes up we are often unable to drill down to the fundamentals because things like their homophobia and fundamentalism get in the way. That is also the reason why Hitler, Mao and the other baddies of human history cause problems because we often can’t get past the deeds to examine the philosophy. This is Marx’s big problem today (and he also deserves an entry in the Matrix.) PS Andreas, check out Eagleton’s latest book “Marx Was Right.”

@thomas

if i understand your point, this article speaks about the dangers of boiling down the founding fathers to their fundamental philosophies and ignoring their positions on the “burning issues”, which if taken into account would shed light on their “virtue” :

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/06/26/the-founding-fathers-were-flawed.html

near the end it also draws parallels between todays issues.

your comment is pertinent, but perhaps you missed Andreas evolution of thought? –

the question has evolved… “It is not ‘where is virtue?’ but ‘where is depravity?’ And the answer is: ‘Tis everywhere. In the nobility, in the peasants, in the king and the cleric…..’

@Douglas – “…..What, exactly, is ‘income inequality’…….”

The income inequality I was referring to was the percentage share of total earnings of all individual Americans, that the highest 10% of earners make. Presently, this highest 10% accounts for about 50% of total earnings of all individual Americans. This was also how it was in 1928.

@Cyberquill – “…….I doubt whether taxing the rich ‘a little more’ will bring about a meaningful reduction in income inequality……..”

Between 1941 to 1979 (“The Great Compression”) the highest 10% of American earners accounted for only 33% to 35% of total national individual earnings. For most of this time (up to 1964) the top tax rate was 90%. Thereafter (to 1980) the top rate did slide, but only to 70%.

From 1981 to today (“The Great Divergence”) the share of total national individual earnings that the highest 10% of earners make, steadily climbed to the current 50%. This period corresponded with precipitous drops in the top individual tax rate, which is now a mere 35%.

This all suggests a strong correlation between how much the rich are taxed and income inequality.

The period of “The Great Divergence” (1981 to today) was also when America’s public debt climbed from $1 trillion to the current $14 trillion – a fourteen-fold increase. However, because GNP, after discounting inflation, doubled during this time, the apparent fourteen-fold increase in the public debt was effectively only a seven-fold increase. But still……….

It would seem, then, that taxing the rich not only “a little more”, but a whole lot more, is the way to go in effectively reducing both income inequality and the public debt.

Well, whatever works. I’m wondering, though, as to the incentive for high-income earners if 70-90% of what they make goes to the government. Psychologically speaking, why bother putting in whatever extra effort the rich may be putting in to earn a lot of money, all the while knowing that most of it goes to Uncle Sam anyway?

The effect of exorbitant taxation on income must be that folks who fall into these tax brackets drastically change their money-making habits, i.e., make a lot less money (at least on the books, i.e., not stashed in various tax havens around the world or otherwise kept out of the government’s reach via various creative methods courtesy of every fat cat’s cadre of tax attorneys) in order to keep more of it, the upshot being that the government gets 70-90% of a lot less than 35% of a lot more.

It may feel nice to know that the rich are being squeezed, but the question is whether this necessarily results in more actual tax dollars flowing into the treasury.

There may be a correlation between higher income tax rates prior to the 1980s and less income equality, but how much of it is causation? Other factors may have been in play which, in days of yore, kept income equality and the national debt lower than it is today. This whole notion of fixing the country by soaking the rich seems a bit simplistic.

@Philippe

The income inequality I was referring to was the percentage share of total earnings of all individual Americans, that the highest 10% of earners make. Presently, this highest 10% accounts for about 50% of total earnings of all individual Americans. This was also how it was in 1928.

And what is so special about 1928? Beyond the fact that it was the year before the Crash of `29? Are you sure there’s a correlation between income inequality and prosperity? And are you sure it is cause and effect? Perhaps there is a correlation. Perhaps income equality reflects prosperity and comes as a result of it.

But you still haven’t defined it (income inequality) or explained what a proper percentage of differences might be or who should determine it.

Perhaps income inequality comes about because some people are better able to find a way to prosper in what might be called “hard times”. Or perhaps it is the natural order of things and a larger income disparity triggers the factors needed to climb out of those “hard times.” Right now, all I see is a jealousy of those who are making a better income than others. A resentment, if you will. I see no “cause and effect.”

I gather this discussion is about the relation of virtue or corruption to power, political theory and privilege. Let me assume I am correct.

I note that you regard James Madison as neutral and that the possibility of an accidental relation cannot be dismissed. Is it true to say, however, that the powerful, of whatever persuasion or origin, naturally seek to secure and concentrate power to themselves and their supporters, thus creating an elite? If this were so, would it invalidate your diagram altogether?

Kindly explain how you can justify using labels here simply because politicians do it all the time. There are dangers in premature classification, if only because it tends to become entrenched and diverts energy from the true issues, which it distorts. You can see it happening even here. In other words, it should not be used as a tentative aid to understanding or research but to illustrate fully justifiable conclusions.This is neither algebra nor geometry. See how Darwin delayed and delayed publication.

Might you agree that the relation is predominantly chaotic and that the need in political systems is to attempt safeguards? Corruption so easily masquerades as virtue, wherever the seat of power and whatever the preconception, prejudice or theory of government.

Perhaps the only true safeguard is to minimise power – is this conclusion justifiable from the available material?

No, I am wrong. These pictures do provide a framework for the early stages of understanding and channel all the ambiguities, cross-currents, contradictions and endless revisions. When the purpose is achieved they have no meaning, of course.

How could I get it so wrong? You were generous enough to share a deeply personal aspect of your creative process.

“deeply personal aspect of your creative process…”

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but yes, perhaps. Thanks for seeing it that way. 🙂

@Cyberquill – “……I’m wondering, though, as to the incentive for high-income earners if 70-90% of what they make goes to the government. Psychologically speaking, why bother putting in whatever extra effort the rich may be putting in to earn a lot of money, all the while knowing that most of it goes to Uncle Sam anyway?……….”

Motivational and psychological studies long ago showed that only up to a certain level is money a motivation to create wealth. The very rich continue their money-making activities for the simple love of just doing it, or for the love of power. Consider only Rupert Murdoch or Warren Buffet. They have more than enough money to keep the wolf from the door, but they keep putting in the long hours everyday making even more money just for the hell of it.

“…….There may be a correlation between higher income tax rates prior to the 1980s and less income equality, but how much of it is causation?……..”

Over the last 100 years there has been so much correlation between the levels of taxation of the rich and income inequality, that if you insist that the level of taxation of the rich doesn’t substantially cause the degrees of income inequality, then the burden of proof that it doesn’t is on you.

@Douglas – “……what is so special about 1928?……..”

1928 was a couple of years after the top income tax rate had been cut from 75% to 46% to 25%. Hence as this rate was dropping, so the gap in income inequality was rising.

“……..perhaps it is the natural order of things and a larger income disparity triggers the factors needed to climb out of those ‘hard times.’………”

Studies long ago showed that income inequality if too wide, hinders economic growth.

1928 was a couple of years after the top income tax rate had been cut from 75% to 46% to 25%. Hence as this rate was dropping, so the gap in income inequality was rising.

“The share of the top decile is around 45 percent from

the mid-1920s to 1940. It declines substantially to just above 32.5 percent in

four years during World War II and stays fairly stable around 33 percent until

the 1970s.”

Click to access saez-UStopincomes-2006prel.pdf

That pretty much says your data are incorrect. Why, it even includes that period called the Great Depression. And that, my friend, suggests they are not correlated.

My opinion of the gap is that it is something used by politicians of a certain persuasion to foster a bit of class envy. That it is the result of manipulation of data. That it is playing to the baser instincts.

@Philippe:

…if you insist that the level of taxation of the rich doesn’t substantially cause the degrees of income inequality, then the burden of proof that it doesn’t is on you.

Of course, if the wealthy get to keep less of their earnings, the wealth disparity between the rich and the poor shrinks, simply because the rich don’t have as much as they had before. The question is whether—and if so, by what mechanism exactly—the rich getting poorer causes the poor to get richer.

“My opinion of the gap is that it is something used by politicians of a certain persuasion to foster a bit of class envy. That it is the result of manipulation of data. That it is playing to the baser instincts.”

@ douglas–does that mean you (a) deny the existence of the gap or (b) that it is a problem? I”m not sure the Romanovs or Hosni Mubarak would agree with either of those statements. At least in retrospect.

–does that mean you (a) deny the existence of the gap or (b) that it is a problem? I”m not sure the Romanovs or Hosni Mubarak would agree with either of those statements. At least in retrospect.

I do not see it as an either/or. I am not in denial of a gap, I am saying that such gaps are manipulated to make them appear worse than they are and that such gaps are more meaningful than they actually are. I could, however, counter with this question:

Are you comparing this administration with the Romanovs and/or Mubarak?

But I won’t. I will stand, therefore, with what a reasonable person might construe from my statement: certain political ideologues use such gaps to inflame emotions in the hopes of garnering votes or take power. As I recall, the enemies of both of those despots used such things quite effectively.

Excuse me… I forgot to turn off the italics after “At least in retrospect”

@Douglas – “……..The share of the top decile is around 45 percent from the mid-1920s to 1940. It declines substantially to just above 32.5 percent in four years during World War II and stays fairly stable around 33 percent until the 1970s ………That pretty much says your data are incorrect. Why, it even includes that period called the Great Depression. And that, my friend, suggests they are not correlated……”

I’m not at all sure that my data was incorrect, as you assert. However, in my previous comments I didn’t talk about the decade of the Great Depression. Perhaps I should have.

Look at the graph on page 6 of the Saez paper, and you’ll see that the top decile was 50% in 1928 as I said. In the 1930s – the decade of the Great Depression (the Great Depression that many think was caused by the excessively unequal distribution of wealth) – this top decile varied between 43% and 46%.

Given that the pre-Great Depression top income tax rate was 25%, and then was suddenly raised under the New Deal to 63% and then to 80%, one might normally have expected this top decile to decline to well below the average of 45% that it was.

However, the pre-Great Depression unemployment rate of 5% rose to an average of 20% during the 1930s. Since most of the unemployed didn’t belong in this top decile, their percentage share of the total national income predictably went far below what one might normally expect. Hence the top decile remained at 43% to 45%.

If the pre-Great Depression top income tax rate had stayed at its 25% during the Great Depression, this top decile would certainly have risen to well above 50%, perhaps to 60% or 70%.

Nice try, Douglas!!

I did nothing more than point out that study and quote from it. I also did something else which I did not relate. I looked for actual income disparity data. That is, I looked for reports detailing, listing, income disparity and I found none.

Where, sir, are you getting your information? You did not mention any source until after I dragged it up and then you used that source and no actual disparity figures. I have difficulty believing I just happened to chance upon your data source.

I repeat, Saez stated “The share of the top decile is around 45 percent from the mid-1920s to 1940. It declines substantially to just above 32.5 percent in four years during World War II and stays fairly stable around 33 percent until the 1970s.”

The disparity, whatever it was, was there in the boom years of 1925 to 1929, did not increase significantly during the Great Depression, and dropped during the war years.

What your chart shows is that high tax rates can impact income disparity. It does not show that income disparity causes anything.

Now, Thomas implies that income disparity leads to revolution in some cases (he mentions 2, I would toss in an obvious 3rd… the French Revolution) but I would point out that the instigators of these unrests merely took advantage of huge disparities which were coupled with extreme social factors of class distinction and oppression to foment upheaval. My contention is that income disparity, in and of itself, is not sufficient to create enough social unrest as to cause such a change in social order. It was the social order itself, in those cases, which eventually brought about that social change. (By the way, the outcome of 2 of the 3 upheavals did not improve the lot of the downtrodden and the 3rd one has yet to work itself out)

I think that income disparity is something that can be used to foster animosity toward certain classes. A useful tool for certain political ideologues. Ones, I suggest, who would simply like to replace the existing oligarchy with themselves.

Look at it this way… I come from a lower middle class income family. We struggled to get by during the 50’s and early 60’s. I managed, without a college degree, to achieve a level higher than my father. I was able to earn more, do more, and build more wealth than he. I did it mostly during those years where Saez says the income disparity was widening. Apparently, it did not affect me greatly.

If I had been an ambitious man, I might have done much more and have become one of those in the upper 5% instead of someone who moved into the upper 20% (barely). the key to that, I believe, would have been that college education which I spurned. The income disparity was not a roadblock, it did not hold me back, we are not a fixed class society.

“……Where, sir, are you getting your information?…….

I got it from the same graph that Asaez used – a graph that has been used in many other similar studies.

When Saez said “The share of the top decile is around 45 percent from the mid-1920s to 1940. It declines substantially to just above 32.5 percent in four years during World War II and stays fairly stable around 33 percent until the 1970s.” he was making his interpretation of this graph.

Isn’t it better to look at the graph itself?

“…..I looked for actual income disparity data. That is, I looked for reports detailing, listing, income disparity and I found none……..”

The degrees of income disparity are right in this graph. The greater the percentage of the national income that the top 10% make, the greater the income disparity between the rich and the poor.

The greater the share of the pie eaten by the top 10%, the smaller the share of the pie for the remaining 90%.

Isn’t it better to look at the graph itself?

Not always. As I have said before, statistics and data get interpreted through a filter of preconception and bias. So, taking the author’s (of the study) take on what the data mean is fairly useful. Once you decide that the author’s words are meaningless because they do not conform with what you believe is not a good thing.

And, of course, as I also said, what are the odds that I would select the very same study that you used? I happen to accept the author’s take on that data because… well, let’s just say I strongly believe he did not limit his analysis to one or two graphs. If he says the data indicate to him that the disparity was essentially stable until the war years, shrunk a bit during the war years (interesting that), and then remain stable until the 70’s, I’d have to think he knows a bit more than someone who looked at one graph.

But that is just me.

I would guess that you know that there is several strata of income involved.Things generally, or easily, don’t divide into The Rich and The Poor. Currently, I believe, the top 1% pay 38% of total income taxes and the top 10% pay almost 70%.

The bottom 50% pay just under 3% (and I understand the bottom 47% pay none at all but receive things like EITC, which is like getting someone else’s refund). That’s a disparity that you seem uninterested in.

But I like Cyrberquill’s question… how does reducing the amount of income at the top (presumably through taxation) increase the income of the bottom?

I do not worry about the income disparity. It is there to inflame passions and incite class envy. Unless there is a lack of a significant middle class and an atmosphere of class oppression, it is not important.

To be honest, I do envy the rich. I would love to be rich myself. But I recognized early in life that I had no ambition, no drive, and no desire to put out the effort to get there. So why should I worry about what they make? It has little to do with me.

Douglas – “…….how does reducing the amount of income at the top (presumably through taxation) increase the income of the bottom?………

By creating jobs. Which is to say by reducing the size of the reserve army of the unemployed.

“……I do not worry about the income disparity……..

Perhaps you should. The more unequal the society the more crime there usually is. Hence the more unequal the society, the more likely you are to be robbed beaten or murdered. This would apply even if you are rich.

The more unequal the society the more the numbers of the unhealthy. It is not for nothing that America, which is the most unequal of all the western industrialised lands, has the highest infant mortality rates of all the western industrialised lands.

The more unequal the society, the less social cohesion there is. Therefore there is less feeling among the people that they all belong to the same nation. One of the manifestations of this is less trust. This loss of social cohesion may well be the ultimate reason why the politicians in Washington can no longer work together.

The more unequal the society, the less chances there are for you to get ahead if you belong to the more unequal class, for too much inequality has been shown to hamper economic growth. On the other hand, too much equality has been shown to hamper economic growth too. Hence it is a good thing to create, through the mechanism of taxation, a society where inequality is neither too much nor too little.

The other western industrialised lands seem to have done this better than America.

Douglas – “…….how does reducing the amount of income at the top (presumably through taxation) increase the income of the bottom?………

Philippe – By creating jobs. Which is to say by reducing the size of the reserve army of the unemployed.

Taxation creates jobs? Not in my reality. Or in he reality of of most economists. You see, government doesn’t create jobs except within itself, it encourages the creation of jobs in the private sector. And it doesn’t encourage that job creation by taking money from the job creators. Add in uncertainty about future taxation and regulation and you encourage the opposite of job creation.

Perhaps you should. The more unequal the society the more crime there usually is. Hence the more unequal the society, the more likely you are to be robbed beaten or murdered. This would apply even if you are rich.

That’s pretty much a myth. While poverty is associated with crime, the unequal society model doesn’t hold up (forgive the pun) under analysis. For instance, the crime rate went up during the War Years (when income disparity was reduced) and back down afterward (when the disparity went back to what it had been). Some attribute the large increase in crime starting in the late 60’s to the Baby Boom. As Baby Boomers hit their teens and 20’s, the criminal population also expanded, With that expansion came an increase in crime. As the Baby Boomers aged, crime has dropped off.

See: http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1963761,00.html

“There’s a catch, though. No one can convincingly explain exactly how the crime problem was solved. Police chiefs around the country credit improved police work. Demographers cite changing demographics of an aging population. Some theorists point to the evolution of the drug trade at both the wholesale and retail levels, while for veterans of the Clinton Administration, the preferred explanation is their initiative to hire more cops. Renegade economist Steven Levitt has speculated that legalized abortion caused the drop in crime. (Fewer unwanted babies in the 1970s and ’80s grew up to be thugs in the 1990s and beyond.)”

No one really seems to know, though.

Hi Andreas – Would you be able to correct the error I made in the italics HTML code at the end of the first paragraph in the comment I’ve just left?

Corrected, Philippe.

And sorry for my apparent silence here. I’ve been on an internet holiday (which I highly recommend), and am only now re-emerging.

@Douglas – You said “…..government doesn’t create jobs except within itself, it encourages the creation of jobs in the private sector……..”

I largely agree with you here. Yes, government (the public sector) does indeed create jobs, which include teachers, policemen, fire-fighters, social workers, soldiers, and whatnot. And government does indeed encourage jobs in the private sector by purchasing goods and services from private firms.

But then you said of government, “……it doesn’t encourage that job creation by taking money from the job creators. Add in uncertainty about future taxation and regulation and you encourage the opposite of job creation……..”

This appears to contradict your earlier statement. Perhaps you can elucidate?

You said of my assertion that the more unequal the society, the more crime there usually is, “……That’s pretty much a myth. While poverty is associated with crime, the unequal society model doesn’t hold up ……….under analysis………”

You doubtless know of the Gini Coefficient, which numerically grades countries by their inequality. And you doubtless know, too, that there are many things one can do which are deemed criminal. One such is murder – about as serious a crime as one can do. The murder rate is a good guide to the overall criminality of a society.

Countries with the lowest inequality (.25 to .24) on the Gini Coefficient scale, like Germany, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Australia, Britain, France, Spain, and Poland, have murder rates of under 1.6 per 100,000.

Countries with somewhat higher inequality (.45 to .49), like USA, Mexico, and Argentina, have somewhat higher murder rates per 100,000 (USA 5.0; Argentina 5.5; Mexico 15.0)

Brazil, with inequality yet higher (.55 to .59), has a murder rate yet higher: 22.0 per 100,000.

These are just a few examples. But they show that murder rates are higher in countries with more inequality than in those with less.

I largely agree with you here. Yes, government (the public sector) does indeed create jobs, which include teachers, policemen, fire-fighters, social workers, soldiers, and whatnot. And government does indeed encourage jobs in the private sector by purchasing goods and services from private firms.

No, I would say it encourages private sector jobs by creating a stable (and some might say “friendly”) business environment by not over-regulating and over-taxing businesses and not changing the rules too often for taxation or regulation. Government is not the source of wealth, it is true that it is a large consumer (just ask the defense industry) for certain things but it is not sufficiently large enough for the auto industry, agriculture, and electronics. You must have a large private sector which can consume. In the U.S. this has traditionally been a large middle class. Squeeze the middle class and you get what we have now… a recession followed by a (in my opinion) false and jobless recovery.

You doubtless know of the Gini Coefficient, which numerically grades countries by their inequality. And you doubtless know, too, that there are many things one can do which are deemed criminal. One such is murder – about as serious a crime as one can do. The murder rate is a good guide to the overall criminality of a society.

When you look at income alone, you leave out a number of other factors which I think are more important. For instance…

“Germany, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Australia, Britain, France, Spain, and Poland” have more restrictive gun laws than the U.S., and greater freedom and more social programs than “Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil.” I see your premise as comparing apples to oranges. I think, also, that it is very difficult to make comparisons between cultures. Most of the countries you named have fairly homogenous cultures. The U.S. is a hodgepodge of cultures and, therefore, has more inherent cultural conflict which may be an additional factor.

But this is merely my opinion, I am not a social scientist.

Douglas – “……Government is……….not sufficiently large enough for the auto industry, agriculture, and electronics……..”

No doubt. But the private sector by itself can never bring about relatively full employment. This can only be done with the aid of government.

“……Germany, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Australia, Britain, France, Spain, and Poland have more restrictive gun laws than the U.S……..”

While this may be so, any assertion that gun laws materially affect the murder rate is, at most, debatable. Arguably, gun laws affect only the law-abiding, since criminals anywhere can get guns whether by fair means or foul. You may find of interest *this piece*.

“….Most of the countries you named have fairly homogenous cultures. The U.S. is a hodgepodge of cultures and, therefore, has more inherent cultural conflict which may be an additional factor……”.

While most do have fairly homogenous cultures, Canada is among those that don’t. Canada has two official languages, has embraced multiculturalism, has a greater percentage of foreign-born than does the US, yet has a murder rate less than a third of that of the US.

“….I am not a social scientist……”

Me neither!!!

No doubt. But the private sector by itself can never bring about relatively full employment. This can only be done with the aid of government.

You’ll forgive me but I almost burst out laughing at that one. Then I became saddened. You see, I happen to believe that if “government” is the answer, then the question is flawed.

What would you call “relatively full employment”? An unemployment rate of 4.7%, perhaps? See November of 2007. You know, under that terrible George Bush. In fact, unemployment rarely went above 5% during his two terms. In fact, it wasn’t until June of 2008 that unemployment went over 6%.

Most all of that was done by the private sector.

But I was saddened because I realized that I will never get you to re-examine your hard core beliefs. I think they’re wrong, those beliefs, but I just do not see any way to make you understand that. I don’t want to convince you, I don’t want to change your mind. The only way that will happen is if you do it yourself. But I don’t think you will look at this objectively. You have your firm beliefs and I have mine. We’ll just have to agree to disagree.

While this may be so, any assertion that gun laws materially affect the murder rate is, at most, debatable. Arguably, gun laws affect only the law-abiding, since criminals anywhere can get guns whether by fair means or foul. You may find of interest *this piece*.

The only truly valid argument I have heard for stronger gun control is the “proliferation” argument. That is, it is the abundance of guns that allows criminals to get their hands on them so easily. Stolen weapons bring a premium and have a large (illegal) market which makes them valuable to thieves. They are also easily hidden and transportable.

I don’t think you really believe much of anything that pro-gun site puts out. This makes this exchange a little upside down; with me arguing the anti-gun position and you the pro-gun.

But when I talked about those other countries, I had to acknowledge that gun proliferation simply does not exist there and that a lack of proliferation helps reduce gun crime all all types.

I don’t necessarily believe that it would work here, we have a long history of gun ownership and it is difficult to change a culture. That isn’t the case in Europe. They have a long history of relying on government and restricting weapons, especially firearms, to that entity. Again, my position is that you cannot make a rational argument based upon one factor; you must examine all possible factors involved.

By the way, Canada is a strong argument but it has its own problems with cultural clashes. The Separatist Movement, for example, which has spawned some violence at times. It also has very strict gun control laws (which has always intrigued me because we share a similar frontier cultural history) which, as I maintain, has to be considered as a factor in violent crime.

But we’re not going to change each other’s mind. Not with these exchanges. I believe the person has to change his (or her) own mind. And the only way he can do that is to objectively examine the issue(s). We (and I include me) often let our preconceptions dictate how we view data. I was once quite liberal. But certain events in my life caused me to re-evaluate my perceptions and my beliefs.

@Douglas – As you were once quite liberal, so I was once somewhat right-wing. But as I went through life and educated myself I could no longer hold on to so many of the fond truths in which I had found comfort and succour.

It would seem we share the experience of having gone through philosophical change, although in opposite directions.

Although we disagree on much, I enjoyed our exchanges. I found them educational and stimulating.

Perhaps we’ll again cross swords in our responses to some of Andreas’s future postings!!!

Education can be a dangerous thing. 🙂

Yes, perhaps will will “cross swords” again. I like to be challenged, I like having to defend my views.

Can the same populist in one country turn out to be a elitist in different context ?

In your foreign policy example of Isolationist vs Interventionist is it possible for both elitist and populist to work hand in glove if the issue is pertaining to a foreign country ?

For example Do both groups believe that US interests are paramount when say for example someone is talking about a infrastructure contract that is being awarded in some far off country ?

Do these two groups Elitists vs Populist align similar to Govt vs Corporation ? Are elitists with corporation and Populists with govt or vice versa?

Open-ended and complex questions, Suresh.

As to the gov/corp dichotomy: No, I don’t think there is an easy and obvious correlation. Corporations might be considered an interest group, a lobby. Populism and elitism, on the other hand, are STYLES of presenting ideas or PHILOSOPHIES about human nature.

As to the isolationist/interventionst dichotomy: Again, no easy correlation that I can see. In American history, you’ve had populist intereventionists and populist isolationists, and elitist interventionists and elitist isolationists. Foreign policy falls somewhat outside the main political markers, which are all domestic. (Compare Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, for example. Those two alone can confuse all these isms.)

As to your first question: That one has potential. Try out a few names on me.