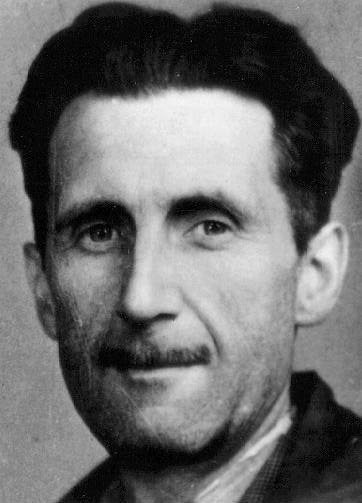

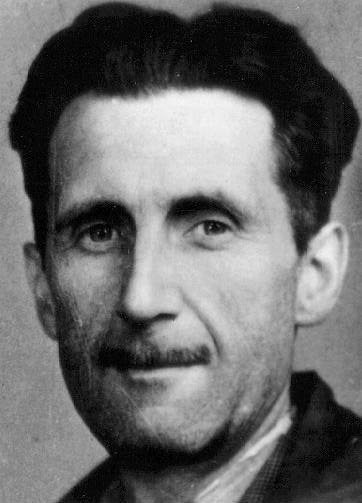

Fear and the English Language is my attempt at a meaningful pun on George Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, one of the most important essays ever written.

You may remember that our own Style Guide at The Economist begins with Orwell’s six cardinal rules of good writing, taken from this essay. And now a reader of The Hannibal Blog has written, and shared with me, a very thoughtful Socratic dialogue based on this same essay (Orwell is Socrates in this dialogue, speaking to a student.) So I decided to re-read Orwell’s essay, which is always a good idea.

What is Orwell’s bigger point? Let me try to put it this way:

Thought + Intention → Words and Words → Thought + Intention

That’s why words are so important. They reflect thoughts and intentions. If your thoughts are jumbled, vague or absent, the words will come out badly, even if the intention is good. If your intention is insincere, the words will come out badly, even if you have a good thought. It also works in the other direction: If you get in the habit of using insincere or evasive words or talking nonsense, you will probably start thinking that way.

And so we can state, as confidently as Orwell did 63 years ago, that most of the words we read and hear by politicians, businesspeople, PR people, academics and celebrities are bad, embarrassingly bad.

Here are the two qualities common to this sort of language, according to Orwell:

The first is staleness of imagery; the other is lack of precision. The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not.

Orwell makes fun of the sort of monstrosity that this led to in his day by “translating” a famous verse from Ecclesiastes,

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

into “modern” English:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

What might that be today? Oh, pick your category. (You can come up with your own best worst phrase in the comments.) Let’s take the businessmen or PR people that I regularly deal with. They might turn Ecclesiastes into:

Whilst it is important to proactively leverage one’s core competencies, market conditions and timing largely determine what becomes a game-changer and what not.

Again, Orwell’s point is that

The whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness.

But why?

1) Laziness, often.

Speaking or writing clearly takes enormous effort because you first have to think, clarify and simplify. On the other hand, speaking or typing words, especially in hackneyed phrases you’ve heard others use thousands of times, takes vastly less effort and fills the time. Yesterday I was interviewing one of the people running in next year’s Californian gubernatorial race: what a torrent of words, in response to every question, and how little I had in my notebook at the end!

2) Fear or cowardice, more often.

This is the real answer, I believe. If you speak or write clearly you end up producing incredibly strong words. If they are noteworthy at all, they are sure to offend somebody. Are you up for that? Most writers are not, which is why they reserve their most honest writing for the grave, as Twain quipped. Usually, people want to speak or write without bearing any consequences. So, as Orwell says, you let your words fall upon the world

like soft snow, blurring the outline and covering up all the details.

This amounts to insincerity. You are really using words to hide. Typically, this is when the mixed metaphors and clichés come out. (By the way, I am not endorsing that American genre–you know who–of writers who see offending people as their niche. You can’t just be offensive, you still need a genuine thought.)

So: good writing, good language, good style comes down to, yes, having something to say and saying it as simply as you can, but above all to the great courage that this takes. That’s why good writing is so rare.