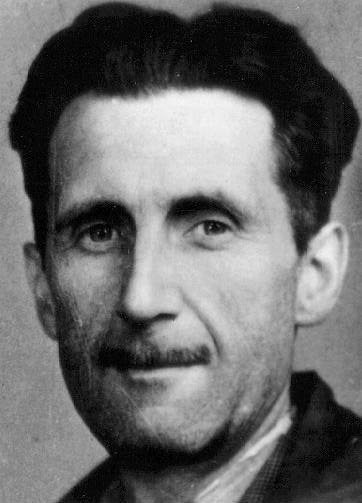

Fear and the English Language is my attempt at a meaningful pun on George Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, one of the most important essays ever written.

You may remember that our own Style Guide at The Economist begins with Orwell’s six cardinal rules of good writing, taken from this essay. And now a reader of The Hannibal Blog has written, and shared with me, a very thoughtful Socratic dialogue based on this same essay (Orwell is Socrates in this dialogue, speaking to a student.) So I decided to re-read Orwell’s essay, which is always a good idea.

What is Orwell’s bigger point? Let me try to put it this way:

Thought + Intention → Words and Words → Thought + Intention

That’s why words are so important. They reflect thoughts and intentions. If your thoughts are jumbled, vague or absent, the words will come out badly, even if the intention is good. If your intention is insincere, the words will come out badly, even if you have a good thought. It also works in the other direction: If you get in the habit of using insincere or evasive words or talking nonsense, you will probably start thinking that way.

And so we can state, as confidently as Orwell did 63 years ago, that most of the words we read and hear by politicians, businesspeople, PR people, academics and celebrities are bad, embarrassingly bad.

Here are the two qualities common to this sort of language, according to Orwell:

The first is staleness of imagery; the other is lack of precision. The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not.

Orwell makes fun of the sort of monstrosity that this led to in his day by “translating” a famous verse from Ecclesiastes,

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

into “modern” English:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

What might that be today? Oh, pick your category. (You can come up with your own best worst phrase in the comments.) Let’s take the businessmen or PR people that I regularly deal with. They might turn Ecclesiastes into:

Whilst it is important to proactively leverage one’s core competencies, market conditions and timing largely determine what becomes a game-changer and what not.

Again, Orwell’s point is that

The whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness.

But why?

1) Laziness, often.

Speaking or writing clearly takes enormous effort because you first have to think, clarify and simplify. On the other hand, speaking or typing words, especially in hackneyed phrases you’ve heard others use thousands of times, takes vastly less effort and fills the time. Yesterday I was interviewing one of the people running in next year’s Californian gubernatorial race: what a torrent of words, in response to every question, and how little I had in my notebook at the end!

2) Fear or cowardice, more often.

This is the real answer, I believe. If you speak or write clearly you end up producing incredibly strong words. If they are noteworthy at all, they are sure to offend somebody. Are you up for that? Most writers are not, which is why they reserve their most honest writing for the grave, as Twain quipped. Usually, people want to speak or write without bearing any consequences. So, as Orwell says, you let your words fall upon the world

like soft snow, blurring the outline and covering up all the details.

This amounts to insincerity. You are really using words to hide. Typically, this is when the mixed metaphors and clichés come out. (By the way, I am not endorsing that American genre–you know who–of writers who see offending people as their niche. You can’t just be offensive, you still need a genuine thought.)

So: good writing, good language, good style comes down to, yes, having something to say and saying it as simply as you can, but above all to the great courage that this takes. That’s why good writing is so rare.

As usual, Orwell (Eric Blair, actually) put it best when he said: “In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act”.

I love this post.

Orwell believed most of us are cuttlefish, squirting black ink all around our bodies in fear. And there is a lot to be afraid of these days.

Language has become so sloppy that so sloppy have become we.

I find this post soothing and empowering. Thank you.

Awesome.

Nelson Mandela makes an interesting point about fear.

In his words, “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us […] There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won’t feel insecure around you […] as we let our own light shine, we unconciously give other people permission to do the same […]”

covering up the details? LIke where is the money going? Don’t ask such imposing questions sir!!!

Since I routinely offend my colleagues (and Friends) , am considered somewhat of a rebel, I can totally relate to this post. It confirms that many of these non-thinking organization-joiners are crazy and just feel more comfortable if everyone around them are speaking in platitudes and they all agree. I am an irritant because I question and will not allow myself to be lock-step with anyone or group that claims to have all the answers and reject honest debate and an openness to consider the thoughts and suggestions of others. I have particularly been disappointed in my fellow whacked-out Democrats who have lost their minds in my opinion. When I have expressed anything different from the lock-step far left wing position, (especially in this election cycle) I have been treated like a traitor. They are driving intelligent and independent thinkers from the party.

This weapon of political correctness is chilling well-intentioned people from exchanging different points of view for the good of the order, and understanding that it is healthy to have such discussions, without malice or a negative response. I predict that this entity will destroy (if it hasn’t already) the functionality of our political system. Our heads will get smaller, people will shake a lot, and the thought police from all factions will be left to fight it out on the pre-text that they are doing it for us.

Feelings of disenfranchisement breeds negativism, hate, and will lead, along with the notion that government will naturally take care of all of us, to underachievement and the slow demise of our country.

Of course it takes courage to express a simple but different opinion than the audience, but it can be a very lonely job when rocking the boat and it is getting harder and harder these days to act locally and think globally.

Sorry, there I go again.

Stevo

By the way, I was just rambling on a subject dear to my heart. I love all you guys here on the Hannibal Blog! I hope I haven’t inappropriately co-opted your blog Andreas. I do think my rant is parallel to the post. I think you now know why I love this site. You can opine, question, and learn a load. Keep it going people!!

SB

Mandela’s quote is powerful. But it occurs to me that I was hasty in describing how fear ruins language. It is not only fear of offending somebody but also all sorts of other fears that make us talk gibberish: fear of not being profound enough (enough for whom?); of not be original enough, witty enough, elegant enough–in short, fear of inadequacy. (I wonder whether Cheri has seen this in her students.) This often leads to pomposity, jargon, etc.

It’s quite an insidious little bugger, this fear….

I see my name up there, so in fear of seeming simple, I will jump in here.

The fear in my students ( please start the cello in low somber strokes ) is the fear of failure. Their parents have not taught them how to fail or what to do when they do…and we all do.

The secret here ( on a blog, at a stuffy party of Harvard or Stanford people, in an interview ) is to maintain that childlike view of the experience. Such a perspective changes EVERYTHING…funerals, weddings, grocery shopping, pedicures, arguments with spouses, teeth cleaning…

I am positive we will learn more about this view in Andreas’s/Andreas’ new book.