Two years ago, I wrote a post called “Fear and the English language“. It was my twist on George Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language, in which Orwell, in his timeless way, indicts and mocks modern writing.

Two years ago, I wrote a post called “Fear and the English language“. It was my twist on George Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language, in which Orwell, in his timeless way, indicts and mocks modern writing.

“The whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness,” Orwell said.

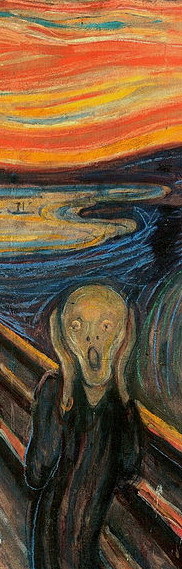

But why is this so? Because we are afraid, I concluded (after interrogating my own brain as it writes). We are afraid of the consequences of our words — of being misunderstood or attacked — so we make the words less clear. We use our words to erect barriers to meaning so we can hide behind those barriers.

This is cowardice. And it leads to bad writing, and bad speaking.

That covers most of verbal communication: the corporate memo, the annual report, the government publication, the politically correct academic thesis, the conference call with dial-in numbers, etc etc.

Well, that old post seems to have resonated, especially with those of you who also write for a living.

One of you, Eliot Brockner, emailed me this:

… I just read a post of yours from a few years ago titled “Fear and the English Language” and felt compelled to write you because of its relevance and timeliness in my own thoughts and struggles to grow as a writer. I think part of the problem is that what I write on a day-to-day basis by nature involves writing with fear. The company I work for covers operational threats to our clients’ businesses (I cover Latin America). To account for any possibility or event, I must use words that make for bad writing – ‘may’, ‘possibly’, ‘likely’. Even though our content is event driven, very little of what we write is concrete.

My problem is that because this type of writing takes up most of my time, my own freelance work – my blog, my writing for other digital publications, even my own personal writing – is suffering. Having to account for so many possibilities in my professional writing is clouding my clarity of thought, and without clarity of thought, clarity of writing is impossible.

How do you break this mold? If you are writing with fear, how do you stop? I’m having trouble reconciling the professional and personal writing worlds.

So Eliot poses the obvious next question: How do you stop writing with fear?

I gave Eliot the honest answer, which is that I have no good answer. (Remember, this is a blog, and most of the time I post stuff that is on my mind, unresolved, not stuff that I have already resolved.) But I promised that I would open it up here, to “crowd-source” it. So weigh in below.

As I ponder Eliot’s challenge, I follow a chaotically dialectical mental trajectory as follows:

1) Arise, inner Hero

Psychologically, writing usually begins as a Quest.

I capitalize Quest to remind you of the archetypes in the thought of Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell. In a writerly Quest, the (usually youthful) writer necessarily sees him or herself as a Hero/Heroine. I had a long-running thread on heroism here on The Hannibal Blog, so let me just pluck from that series two very clean and simple kinds of hero:

One kind of writer, after reading Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, seethes with bravery and becomes Theseus after he moves the boulder and finds his father’s sword: He wants to go out and prove himself, to slay villains on the way to Athens and then the Minotaur.

Another kind of young writer becomes The White Rose and decides to challenge evil with courageous words, by telling truth to power, by not shutting up, risk be damned.

To pick, somewhat arbitrarily, two analogous examples from our time:

In Hitchens’s case, we see a self-conscious hero dazzling us with his word prowess right from the first line of anything he writes. He knows he will have enemies (the whole point is to make enemies!), so he tilts at them with a cavalier smirk, with utterly gratuitous bravado, and says “bring it on.” Whatever you think of him, whether or not you agree with him, he regularly overcomes his fear and writes well. Orwell would approve.

In Krugman’s case, he sees (in much less intense form) in American Conservatism what the White Rose saw in Nazism: a curse to be opposed with relentlessly clear polemical writing. He does not hedge, he does not mince, he does not dilute or duck or hide. Whatever you think of him, whether or not you agree with him, he regularly overcomes his fear and writes well. Orwell would approve.

So Eliot, you could try to be a Hitchens/Theseus or a Krugman/White Rose. To hell with clients, employers, editors, readers: excise those hedge words, make those tenses active, replace those Norman words with Saxon ones, make those thoughts as clear as they want to be.

2) Sit down, you’re no hero

But wait, Eliot: What if you’re not a Theseus or a White Rose?

Oh, and by the way, when Theseus became unpopular in Athens, somebody threw him off a cliff. And the members of the White Rose were beheaded. So what if you pick a heroic fight and … lose? You’ll still have to pay the bills and rent or mortgage.

So let’s remember that good writing is rare precisely because it is dangerous. Somebody who leaps to mind is Satoshi Kanazawa, the scientist we debated so passionately in the previous post. In our discussion, we mainly argued about his academic freedom, his integrity as a scientist, his rights and privileges in the pursuit of truth. Those are the appropriate questions.

But I also see in him the struggle we are talking about in this post. He did not want to dilute his hypotheses into the usual term-paper bilge. He wanted to make the words simple and clear. As ever, simplicity and clarity in writing make the words stronger and more powerful. And that’s what sealed his fate when he wrote the title of the blog post that suspended his career:

Why Are Black Women Rated Less Physically Attractive Than Other Women, But Black Men Are Rated Better Looking Than Other Men?

Give Eliot or me five minutes, and either of us could edit Kanazawa’s original post in such a way that nobody would take offense. How? By hiding the hypothesis behind hedges, passive tenses and qualifiers so deep that you wouldn’t even be able to find it. Kanazawa’s post would then be titled:

Preliminary implications of factor analysis on the aesthetic variance observed among gender and race phenotypes

(This sort of thing happens all the time, by the way: Coincidentally, I found another old post of mine in which I lament the New York Times doing this, with another topic vaguely mixing science, sex and race.)

The writing would be awful, yes. Orwell would not approve, except in his ironic Orwellian way. But Orwell does not own Psychology Today or run the LSE. Satoshi Kanazawa might still be blogging. This could all have turned out differently.

So maybe, Eliot, you and I are right to be circumspect. Let’s write, you know, fine, not too well. Let’s save the good stuff for later, for a special day. We would be in good company: Even Mark Twain concluded that you can only write honestly when you’ve got nothing left to lose:

Free speech is the privilege of the dead, the monopoly of the dead. They can speak their honest minds without offending.

3) If you can’t be a Hero, don’t write at all

But that’s not satisfying. I didn’t become a writer to write badly. If this is the way it is, Eliot, let’s rather not write at all.

And again, Eliot, you and I would be in excellent company: Socrates refused to write anything at all, because the written word cannot defend itself, whereas the spoken word (in his opinion) can. As soon as you write something down, said Socrates, the words will be misunderstood or distorted, by the dumb or the malicious, and your words

must remain solemnly silent.

4) If you must write, at least pick your battles

Clausewitz

But that’s not satisfying either. We became writers because we love writing, and because we do occasionally have something to say.

So perhaps, we must integrate all these strands into something practical. This brings to mind Clausewitz and the distinction between tactics and strategy.

Let’s distinguish between means and ends, between important battles and distractions and diversions, between the individual words and the intended meaning, between each instance of writing and an entire writing career.

I suspect, Eliot, that we would then:

- sometimes follow Socrates and choose not to write at all,

- sometimes follow Twain and choose not to write yet,

- sometimes compromise and choose words that make smaller targets but retain power,

- sometimes go heroic and stumble, as Kanazawa did, then get up again and keep going, and

- sometimes revert to our inner Theseus or White Rose, decide that now is the time for our arete — all consequences be damned — and write really fucking well.