Alexander Hamilton is “my favorite” Founding Father, as I’ve hinted several times before. But I’ve never actually explained what I meant by that.

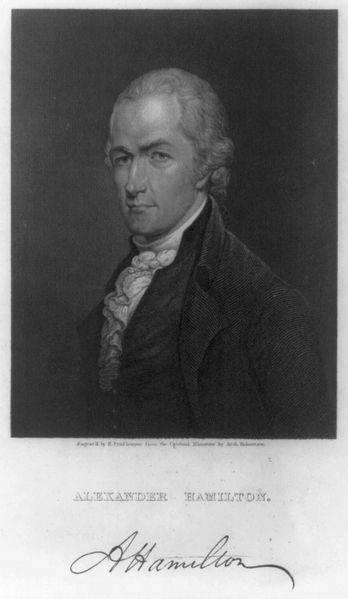

In this and the next post, I will try to unravel which aspects of this complex, visionary and soulful man (just look at that portrait above!) so resonate with me.

- In this first post, I’ll sketch the man, his temperament, his journey and philosophy about people and life.

- In the next post, I’ll describe his intellectual contribution to American governance and political philosophy.

You’ll see after the second post that the man can’t be separated from his ideas, nor the ideas from the man. And you’ll see (I hope) how timeless — meaning: relevant today — Hamilton is.

I will give you my interpretation, but my main source is Ron Chernow’s excellent biography of Hamilton. (I am now reading Chernow’s new biography of George Washington as well.)

Now, to Hamilton, the man:

1) He was an outsider who ended up on the inside

Hamilton was the only Founding Father born outside of what became the United States. He was born in a Caribbean hellhole (called Nevis, in the West Indies) that seemed to specialize in tropical diseases, random violence and the slave trade.

And he was born as an ‘outsider’ in another way: he was illegitimate. His mother was not married to his ostensible father, James Hamilton, and even James Hamilton was probably not his biological father (instead, that seems to have been a gentleman by the name of Thomas Stevens).

His childhood was rough. When Hamilton was a teenager, in the space of a few years,

- his mother died,

- his father vanished,

- his aunt and uncle and grandmother also died,

- his cousin committed suicide, and

- Alexander and his brother were disinherited and left penniless orphans.

As Chernow puts it:

that this fatherless adolescent could have ended up a founding father of a country he had not yet even seen seems little short of miraculous.

2) He had an open mind

This experience might mark him as, yes, an American archetype: The Immigrant Who Reinvents Himself.

Reinvent himself he certainly would — several times throughout his short life, and in a unique, and uniquely compelling, way.

He began by getting himself to America. Through savvy, wit, charm, chutzpah, and luck, Hamilton found himself on a trading ship to New York, with an allowance from an older mentor and a job that gave him a bottom-up view of international commerce, shipping and smuggling. (Much later, this expertise would serve him well, when he founded the US customs service and Coast Guard.)

Already his mind was expansive, open to new worlds, both of experiences and ideas. Coming from the Caribbean, he was bilingual in English and French (although, unlike Franklin, Jefferson and Adams, he would never set foot in that superpower of the day).

He was, in a word, cosmopolitan. And this would, yet again, mark him as an outsider in America. For America has always had, and continues to have, an ambivalent — nay, schizophrenic — relationship with cosmopolitan types. Yes, Americans sometimes admire and appreciate them and their perspective. But they also distrust cosmopolitans and are ready to exclude them at a whim — by calling them elitist, for example, or insinuating that they are not real Americans.

Hamilton was also unapologetically erudite, immersing himself into the classics, and in particular in Plutarch, one of my favorites. Among the Founding Fathers he was in good company in this respect, for they all valued intellect and learning. But in America at large this erudition would — yet again — make him potentially suspect, for America has always had, and continues to have, the same ambivalence toward intellectuals that it has toward cosmopolitans.

3) He had a romantic sense of honor

His illegitimate and Caribbean background, and his cosmopolitan style, made him vulnerable to attacks on his reputation. Understandably enough, Hamilton was therefore unusually touchy about his good name, and fiercely keen about defending it. He was an Enlightenment man who believe in reason and law, but he simultaneously retained an older, classical, romantic, even Homeric sense of honor.

His thirst to earn and defend his honor — and specifically his American and patriotic honor — made him demand to be in battle, in the line of actual fire. So he fought with extra valor in the war and came to the attention of George Washington. Hamilton was 22 and Washington 43 when the general made the young man his protégé and chief of staff, giving Hamilton not only a perfect view into American history as it unfolded but a role in shaping it.

Washington was tall, imposing, dignified, laconic and kept his emotions bottled up. Hamilton was five foot seven, slim and athletic, elegant, gave his emotions free reign and was so articulate that he talked himself into trouble as much as out of it. The two men, so different and yet like father and son, would form one of the most important relationships in history.

Hamilton yearned to be more than chief of staff. He wanted to become a war hero, by commanding troops and risking his life. At Yorktown, Washington gave him that command and Hamilton became that hero, after fighting as though driven by a death wish.

In this respect, Hamilton was certainly very different than those Founding Fathers who would become his enemies — above all Jefferson, who somehow always found himself where there was no physical danger, and in one case (when he was governor of Virginia) actually fled on horseback from fighting, for which he was accused of dereliction of duty.

(Remember this when we get to the next post, and the hyper-partisan fight between Jeffersonians and Hamiltonians.)

4) He was ethical but all-too-human

The biggest ethical issue of the day was, of course, slavery. And how did Hamilton regard this institution?

As despicable and evil. He was unambiguous and clear about it. He was the first and staunchest abolitionist among the Founding Fathers.

To us this is a no-brainer, but to Americans at the time it was not. Washington, Jefferson, Madison and all the Southern Founding Fathers owned, bought and sold slaves. They may have had qualms, but never enough to free their slaves or to push for abolition (Washington was the only one of them to emancipate his slaves after his death). This, of course, is the founding irony at the heart of the American idea: Thomas Jefferson owned human beings at the very instant in which he wrote the words “… life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

So Hamilton was unusual in that he was ethically on the right side of this issue. Which would make it all the more ironic — in that inevitable American way — that his political enemies, including some of the aforementioned slave owners, would later try to paint him as immoral.

How? The way one does this in America: with a sex scandal. Hamilton, stupidly and unnecessarily, allowed himself to be seduced. It was America’s first public and politicized bimbo eruption, a sort of proto-Lewinsky affair. It is of no interest or consequence to us, but it was in its day.

Hamilton was certainly a charmer and flirt. That episode aside, however, Hamilton was also a devoted husband and father, perhaps because he had never had a father. He and his wife had an intimate bond. And his eight children meant everything to him. When his oldest son, handsome and also sensitive about his honor, died in a duel, Hamilton went to pieces in grief.

5) He had a nuanced grasp of human nature

From his reading of history and the classics, and his own upbringing in the West Indies, Hamilton developed a sophisticated worldview that was somewhat pessimistic about human nature, at least in comparison to the — then as now — reflexive and simplistic optimism that usually wins arguments in America.

Thus he saw the potential evil of tyranny — which, of course, he was actively fighting with Washington in the war against the British crown — but he also saw the potential evil of mobs, of anarchy. There was a lot of violence in those days, much of it directed at Tories or loyalists, who might easily end up tarred-and-feathered or even lynched. But Hamilton, even though he fought for the republic, always remained humane towards individuals on the other side — and wary of mobs on any side.

Our countrymen have all the folly of the ass and all the passiveness of the sheep in their compositions,

he once said. And that would lead him to say things such as this:

We should blend the advantages of a monarchy and of a republic in a happy and beneficial union.

But that will be the segue to the next post.

6) He died as he lived, but too young

But before I hand over to that next post, just one final anecdote that gives a glimpse into his character. Because he guarded his reputation and honor so jealously, he had, on occasion, to duel. He certainly saw the folly of dueling as he got older. He must even have hated it after he lost his beloved son in a duel.

But when, in the ordinary course of bitter partisan politics, certain things were said between him and a vulgar mediocrity named Aaron Burr, Hamilton picked up the very pistols his son had used, rowed across the Hudson to New Jersey (duelling was illegal in New York), and met his challenger in a clearing by the river.

It appears that Hamilton shot first, but “threw his shot away”, in the parlance. In other words, he deliberately missed by firing into air, thus signaling that both parties had satisfied the requirements of honor and could end this business without shedding blood.

Then it was Burr’s turn. But Burr had a different sense of chivalry. He aimed at Hamilton and found his target.

Hamilton, in convulsions, was rowed back to New York, where he died many agonizing hours later, as his family and city grieved over the loss of a great man, who, aged about 47, had already changed the world in ways that would only fully become clear generations later.