What might Clausewitz say today about America’s double-war in the Middle East during this decade?

I was very tempted not to write a post on this. After all, in my forthcoming book I am ‘only’ using success and failure in war (ie, the one Hannibal and Scipio fought) as a primal metaphor for other contexts in life such as sports, love, business, relationships, exploration, reproduction, art and thought.

Ditto Clausewitz: I am interested in life strategy; but that is still strategy, and Clausewitz happens to be the sage on that subject.

(Incidentally, I’m impressed by the feedback I’ve gotten from that little post. Clausewitz is very topical, it seems. For instance, Mike Lotus emailed me to point out his recent roundtable on Clausewitz, which will become a book this fall.)

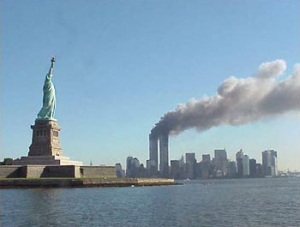

I am also aware that there is little to be gained from yet another analysis of where we went wrong in responding to 9/11. Everything has been said. Worse: in contrast to, say, the Korean War or the Second Punic War, our current wars are still going on and our society is still split, so it is too early to talk dispassionately about them.

But I’ve decided that if I bring up Clausewitz and strategy, I would be chicken not to take a stab at Iraq and Afghanistan. So here goes.

The situation as it appeared on September 12, 2001

Al-Qaeda attacked us; 3,000 of us are dead; 300 million of us are shocked, angry and scared.

1) From Al-Qaeda’s point of view

For Al-Qaeda, this was an ideal alignment of tactics and strategy: With little effort and cost, it caused disproportionate levels of terror (hence ‘terrorism’) in the Western world that appeared (politically and psychologically) certain to provoke us to go on an offensive. (Notice ‘an’, not ‘the’.)

Clausewitz believed that defense was much easier than offense, because whoever is attacking will eventually reach a ‘culminating point‘ point at which he is overextended and exhausted, and the defender can counterattack with devastating ease. So if we play offense and Al Qaeda plays defense, that helps them. (This is the opposite of what Cheney thinks.) Al-Qaeda was pleased.

Clausewitz also believed that, to win a war, you need to find your enemy’s center of gravity and defeat him there. Defeating him elsewhere is pointless or counterproductive. (For Clausewitz the obvious example was Napoleon‘s mistaking Moscow for Russia’s center of gravity, an error that was the beginning of his end.) Al Qaeda knew

- that its center of gravity was not one that we were trained or able to identify militarily, because it had no capital and no army that we could bomb; and

- that we were likely to miss its ultimate center of gravity, which is its support among Muslims at large.

Al-Qaeda might have believed (although we might be giving them too much credit) that our center of gravity was … us! If we could be terrorized into compromising our values then we might forfeit any appeal we might have for moderate Muslims around the world.

“War is nothing but the continuation of policy with other means,” Clausewitz said, and Al-Qaeda’s overarching policy was and is to defeat moderate or secular or Shia Muslims in Muslim countries. Any tactic (or means) that would weaken the moderates in those countries and strengthen the extremist Sunnis would therefore fit into its strategy (or end).

If we could be provoked into disarming (ie, no longer offering appealing values to moderate Muslims) and attacking the wrong center of gravity (=Napoleon to Moscow), then a Wahabi-Sunni caliphate, united against Shias and the West, would become more likely. Al-Qaeda would consider this victory.

2) From our point of view

For us, 9/11 was a wake-up call. There were people who were trying to kill us, and even though they had only box-cutters (and hence our planes) they might get nukes. We had to keep nukes and other WMDs out of their hands, and to keep our enemies out of our countries altogether. Strategically speaking, so far, so good.

Problem Nr 1: Offense or defense? Clausewitz said that defense was better. Even in this case, he might be right. After 9/11, there was a global outpouring of sympathy for America. In Europe, Asia, even in the Middle East, reasonable people were on our side. For Al-Qaeda, this might have been an early culminating point, an act of over-reaching that could have united us with our allies and even some enemies and estranged moderate Muslims from Al-Qaeda, thus leading to its defeat.

But defense was not an option, for reasons of domestic politics and psychology, and Al-Qaeda knew that. Hence…

Problem Nr 2: Since we were going on the offense, what was the enemy’s center of gravity? The difference between going on the offensive as opposed to an offensive is one of aim: if we hit, it’s the; if we miss, it’s an. So was the center of gravity

- Osama?

- Afghanistan?

- Al-Qaeda everywhere and anywhere?

- Its sympathizers anywhere?

- Muslims?

- The arms, ie the WMD, wherever they were, that might fall into Al-Qaeda’s hands?

You see the difficulty. As it turned out (but we could not have known that then), any item on the list above that seemed easy and straightforward subsequently turned out to be hard and elusive.

- We thought we could get Osama quickly (but worried even then that he personally was not the center of gravity–correctly, I think). But here we are and he is, well, somewhere.

- We thought we could do better than the Soviets, and as well as Alexander the Great, and just subdue Afghanistan. And we did. But then we didn’t. Or did we?

What we should have realized even then is that the center of gravity was the rest of that list.

- “Al-Qaeda everywhere,”

- “its sympathizers anywhere,” and

- “Muslims”

were and are three disctinct but fluid and overlapping populations. If we were to “win over” Muslims, then there would be fewer sympathizers, and thus also fewer (new) members of Al-Qaeda.

What would that have entailed? Borrowing a bit from Lao Tzu, we might have done a lot less, because Al-Qaeda is so appalling to most Muslims. (Most of the people Al-Qaeda kills are Muslims.)

We might also have contemplated a full-fledged “Muslim Marshall Plan”, on the scale of the one that we brought to Germany and Western Europe after the war (against our then-new enemy, Communism). The earthquake in Pakistan and events like it were great opportunities, largely overlooked, to show them what we can be and what Al-Qaeda is not.

We did neither of those things. Instead, we got more active than Al-Qaeda, and blew up more than we built up. That was a strategic mistake, but not nearly as big as the following:

- The arms (ie, the WMD)

No, I am not talking about merely getting our intelligence about Iraq wrong (as tragic as that was). At the time (defined as: after Colin Powell’s presentation to the UN) we all thought that Saddam was making WMD.

But so what? The strategist (Clausewitz) would step back and look at the overall situation:

- a risk of loose nukes in the former USSR. Must secure as fast as possible!

- Pakistan, which is Muslim and next to Afghanistan, having nukes. Must support and stablize country! Check back in often.

- North Korea, which was on the verge of getting nukes, but still had our (IAEA) monitors inside the country. Must contain and engage! Otherwise consider pre-emptive strike!

- Iran, which was far behind North Korea in progress toward nukes, domestically complex, our enemy but also Al-Qaeda’s enemy. Must attempt to turn into potential ally against Al-Qaeda!

- Iraq, which was furthest behind, mostly dabbling in chemical and biological WMD (I’m still quoting what we thought then), which are infinitely less dangerous (harder to deliver, less lethal). Our enemy, but also Al-Qaeda’s natural enemy. Must attempt to turn into tool against Al-Qaeda!

I’m guessing that several of those points caused you whiplash (the bits in italics). But remember that the idea of Nixon going to China would have caused you whiplash too.

What we did not do, but should have done, is to think strategically about the world’s nukes. A clear hierarchy of danger existed, with North Korea at the top and Iraq not even on it.

What we also did not do, but should have done, is to think strategically about enemies and allies (as Nixon and Kissinger did). The biggest enemy was Al-Qaeda. Iraq and Iran were holding each other in check (thanks to Bush senior who, in a masterly and subtle gesture, pulled back in the first Gulf War just at the point that would allow Iraq to keep holding Iran in check.)

More importantly, Iran, being Persian and Shia, and Iraq, being secular and Baathist, were both natural enemies of Al-Qaeda. Duh!

I will never forget the day I came back from the slopes in Whistler on a ski holiday with my fiancee (now wife), turned on the TV and watched the news of North Korea kicking out our monitors. That was it. That was the moment I knew we had screwed up. (And we did not even know yet that Iraq had no WMD.)

Kim Jong-Il was watching what we were about to do to Saddam and decided to make a run for it–ie, for the nukes. Until we invaded Iraq, we had everyone in a tense stalemate: Saddam could not move and had monitors in every orifice, Kim Jong-Il had monitors, and Iran was worried about Iraq as much as us. After we invaded Iraq, North Korea and Iran called our bluff: We were not going to “pre-empt” anybody again.

The rest is history

- We invaded Iraq and found no weapons, even as we watched North Korea get nukes and Iran follow close behind.

- We weakened Muslim moderates in their own domestic debates against extremists by becoming what Al-Qaeda needed us to become: torturers, abusers of Muslims at Abu Ghraib, bombers of civilians. We gave them a Feindbild.

- At home, once we realized we were not advancing our strategy–indeed, not even formulating it properly–we began confabulating other war aims. Suddenly, it was about “democracy”, and bringing it to a region at gun point. This was somehow going to solve everything. This is when I became disgusted.

Summary: We kept sympathy for Al-Qaeda alive longer than was necessary and allowed nukes to get into the hands of people who might yet trade them to Al-Qaeda. Strategically speaking, an utter disaster.

Fortunately, the story is not over yet and, with luck, we will look back at the Bush years as merely lost time, not an irreversible defeat.