Tom Friedman was in Berlin this week, hosted by the American Academy, to make himself smart on Germany and to begin plugging the book he’s working on, “Thank you for being late”.

Sipping drinks on a Charlottenburg rooftop before a dinner given for him, Tom and I were talking about one of the many ideas he is pursuing in that book, which is that humiliation is the driver of events in the Middle East today. Young male Arabs in that region arguably feel more humiliated than any other group in the world today. That puts them at extra risk of drifting into the various forms of nihilism. Young Arabs in the banlieues of Paris and other European cities also feel humiliated and are also at risk.

Then Tom and I pondered whether humiliation drives human action (and thus history) more generally. The Germans after World War I felt humiliated by the “peace” the Allies imposed on them, and that humiliation, probably more than hyperinflation or depression, drove them into the arms of Hitler. Today, the Russians feel humiliated by the “peace” the West and NATO imposed on Europe 25 years ago, which appears to make them surrender willingly to the propaganda of Putin. And so on.

Just then I had an embryo of an idea and dropped it into the conversation: Marx was wrong, I said. It’s not the mode of production that is the base, with everything else being the superstructure. Instead our sense of dignity or humiliation is the base. The base is thus not materialistic but psychological.

Tom was intrigued by that half-formed thought so we met again on Saturday at the American Academy’s beautiful lake-side villa for a long talk, marred only by that day’s pollen count, which left me a red-eyed and sniffling hunk of misery. Tom wanted me to flesh out the idea. I’m hardly an expert on Marx. But we ruminated on it for a while and came up with a hypothesis along the following lines, which I would now like to test on you.

Marx was a Hegelian, ie a follower of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whom I’ve called “the archetype of the Teutonic windbag” on this blog before. Hegel thought, in his convoluted way, that history was a process that led, via many surprising turns, to a higher end state. So Marx wanted to one-up Hegel by explaining what the mechanism or driver of that historical process was, and what the end state looked like.

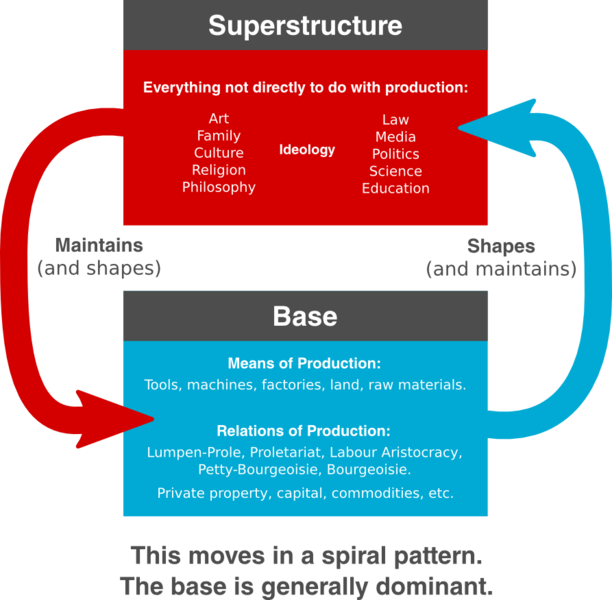

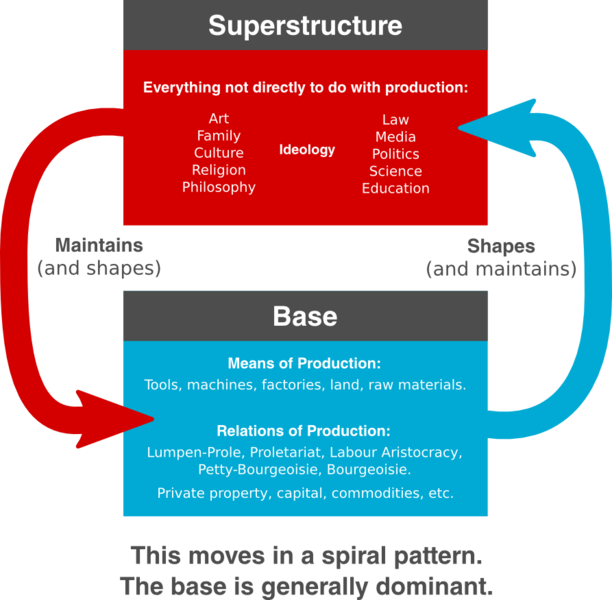

Marx called the driver the “base” and postulated that it was the mode of production — ie, how and by whom things are made in a given society. That thinginess is the Marxist “materialism”. (If I am wrong, you experts, please correct me in the comments.)

Everything else — ideas, thought, art, music, religion, politics, relationships — is but the “superstructure” built on top of that base. User “Alyxr” on Wikipedia depicts it thus:

In his own time, Marx thought, Europe had gone from feudalism to capitalism. A new class, the bourgeoisie, had taken over from the feudal lords as the owners of the means of production. This capitalist bourgeoisie now determined the superstructure. But as more and more of the workers on the capitalists’ payroll felt exploited (“humiliated”?), they would eventually rise up, ushering in socialism, and eventually communism. That would be the Hegelian end state.

So Marx thought that production was the deep-down driver of human action, in the way that Nietzsche thought it was power and Freud thought it was sex. But as Tom and I scanned today’s landscape, we started thinking that maybe humiliation was the more powerful driver. We see it in China, for instance, where a synthetically hyped “memory” of the humiliations by the West and Japan play a big part in driving progress.

I see it in America: Many blacks feel humiliated by cops in certain places. Prisoners feel humiliated by the reigning punishment mentality in the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world and in history.

I also see it in eastern (ie, “East”) Germany, where many Ossis march in the so-called Pegida demonstrations in Dresden against foreigners. Like members of the Tea Party in America, Pegida followers tend to be middle class and middle-aged and thus objectively not at the exploited end of any mode of production. But they have a subjective sense that they were marginalized in a reunited and politically correct Germany and feel humiliated.

I think postwar Germany, given what it had just committed, recognized this primacy of humiliation in 1949 by enshrining its positive opposite, dignity, in the first article of Germany’s new constitution:

Die Würde des Menschen ist unantastbar.

(The dignity of every human being is inviolable.)

Despite this post’s title (which is meant to provoke), the idea is not to suggest that humiliation/dignity should become a new base, with everything else becoming its superstructure. I don’t see, for example, how humiliation (as opposed to technology) could determine the mode of production. And there are plenty of people who don’t feel humiliated but make history nonetheless. So there probably is no single base, and trying to pick one was the real error of Marx and people like him.

But the need for dignity, and the power of humiliation, nonetheless seem basic. Whenever dignity is violated (much more than when property rights are violated, for example) human beings will react. The more humiliated they feel, the stronger their reaction will be. That’s not how all of history is made. But it’s how much of history is made. And because people will always humiliate and feel humiliated, history has no end state.