Marianne, above, did not flash her boobs to all those corpses for nothing. She did it for the trinity (as in the tricolore she carries) of liberté, égalité, fraternité. Let’s leave fraternity, which is a rather mushy notion, to one side. That leaves liberty and equality. Do those two belong together?

I knew I would have to address this issue sooner or later in my ongoing ‘freedom lover’s critique of America‘. But the fascinating debate in the comments below this post brought it to the fore. Fortunately, that comment thread neatly summarizes the entire spectrum, across the world and history, of views on the subject. As I see it, the three options are:

- You can’t have freedom without equality.

- You can’t have freedom with equality.

- It’s complicated.

The Classical Liberal view

Broadly, classical liberals (as properly defined) are passionately in favor of equal opportunity and just as passionately against enforced equal outcomes, exactly as “Hizzoner” paraphrased Friedrich von Hayek here.

Which is to say: If you (ie, the government) predetermine that everybody will be the same (think the same, dress the same, drive the same car, live in the same house…) then nobody in your society can be free, if ‘free’ means being able to be yourself, ie different than others. Why create, why achieve, why risk, if the fruits of your effort and ingenuity will be confiscated (“redistributed”) in the name of equality?

I personally glimpsed the extreme form of just such a dystopia when I peaked into East Germany months before it crumbled (although I didn’t know that it would crumble, of course). They were all driving, or on the waiting list for, the same damn Trabi. And while I was ogling their Trabis, many East Germans were already flooding into the West German embassy in Hungary, trying to escape and eventually forcing their leaders to let the Berlin Wall crumble.

That same example, East Germany, also showed what Hayek correctly predicted would happen in reality in an ‘egalitarian’ society. As Orwell might put it: Some were more equal than others. The difference was that the ‘more equal’ ones didn’t use wealth to assert their supremacy but more nefarious means–party connections, or what the Chinese call guanxi. The resulting horror was captured intimately on screen here.

And so, to those of us, like me, who were devotees of Ayn Rand, the answer was clear. Equality is the enemy of individualism, and thus of freedom.

How it got complicated for Liberals

Even at the time, however, there were some contradictions that gnawed at me. Even in the ‘free world’, we were often invoking equality. For instance, democracy, which we (perhaps wrongly) associated with freedom seemed to be based on the equality of one citizen = one vote, even as capitalism seemed to be based on the opposite, ie unequal outcomes.

Then there was the bit about equal opportunity, which we were all supposed to be for. Well, this was messy, because, inconveniently, we were biological organisms and as such insisted on looking after our offspring. Anybody who ‘makes it’ devotes his entire life, and all his resources, to ensuring that his offspring get a head start. And who can blame him?

So if ‘we’ (the government) really wanted to preserve equal opportunity, we would have to get heavy-handed and stop ‘him’ from looking after his kids. We would have to stop him not just from sending his kids to better schools and doctors, but from reading his kids all those bedtime stories, paying for all those piano lessons and SAT prep courses, building all those Lego houses with them–ie, from doing all those things that give kids ‘unequal’ opportunity. In short, we would have to take his freedom away! Obviously, a non-starter.

The triumph of biology

And then I saw a documentary. I tuned in somewhere during the middle and never saw the title, so I can’t be sure it is this one, but it might be. It was based at least in part on Sir Michael Marmot’s Whitehall Study from Britain. Here is how I remember it:

Stress: It is not the same as pressure, which we all feel from time to time. Instead, it comes from ranking low in a hierarchy and lacking power over your own time, your own self (=not being free). You who are at the bottom are at the whim of others. You suffer. And not ‘just’ psychologically, but biologically. You tend to get fat in your mid-section, and your heart, blood vessels and brain change visibly, with entire neurological circuits shriveling up. Meanwhile, the brains and hearts of top dogs expand and thrive.

The most poignant moment came when they cut from our species, Homo sapiens, to monkeys. The researchers observed packs of primates, and sure enough: a monkey at the bottom of the hierarchy got fat in his mid section, had hardened arteries and heart walls and a a shriveled brain.

Equally poignant: One group of monkeys, led by particularly aggressive alpha males, played in a trash dump and was decimated by an epidemic. Another group, more female and egalitarian, moved in and absorbed the survivors of the first group. The egalitarian culture prevailed. And voilà, the health of the surviving monkeys from the first group recovered and improved! They were slim, their hearts and arteries pumped, their brains fired on all neurons.

Let’s take this one more step toward generalization: You recall that I criticized Ayn Rand for getting individualism wrong (which took me many years to figure out). Well, I now know how she got it wrong. She did not allow or understand how inviduals, when forming groups, pick up signals from one another that change who and what they are.

Watch this amazing TED talk by Bonnie Bassler as a mind-blowing illustration of what I mean. It is not about humans per se, but about bacteria. That’s right. Stupid, single-cellular strings of DNA and surrounding gunk. The trick to understanding bacteria (→all biological critters?) is to grasp how they chemically detect the presence of other bacteria, and then suddenly change their own chemistry. Upshot: No bacterium is an island.

The case of America

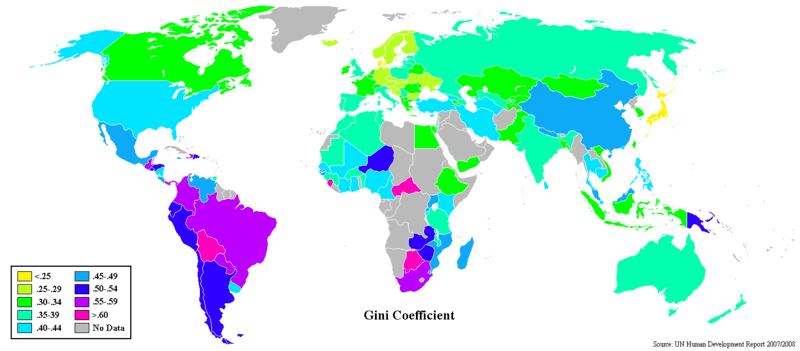

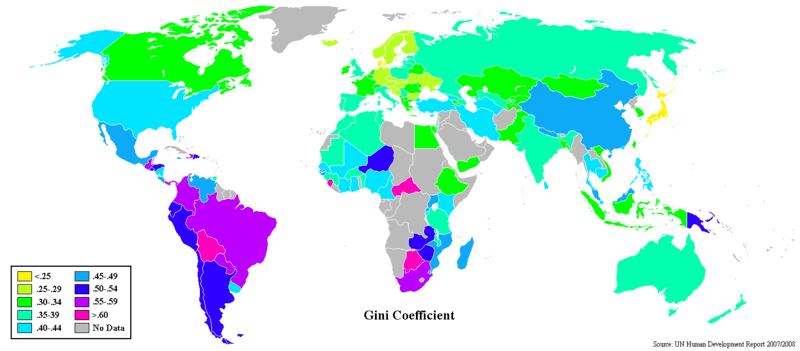

Let’s now look at America. Without getting into the academic weeds, there is a proxy for social equality called the Gini Coefficient. If the coefficient is 0, everybody has exactly the same; if it is 1, one person has everything, and everybody else has nothing. So countries fall somewhere in the middle between 0 and 1. Now look at this world map:

The first thing you will notice is that the darkest blues and purples–ie, the greatest inequality–tend to be in poor countries, even in nominally “Communist” ones such as China. That’s because poor countries tend to be corrupt and feudal, with a few lords and many serfs. It is hard to consider these countries “free”.

But the second thing is more interesting. If you look at just the “developed” countries (let’s say those belonging to the OECD), you notice that one country stands out.

All the rich countries are in shades of yellow or green, meaning that they are fairly egalitarian societies. Only America is blue. America, in short, is the least egalitarian of all the developed countries.

And so? I’m not sure. The old Hayekian in me would chalk this up as a possible sign of more freedom in America than elsewhere. The new bacteriologist and epidemiologist in me wants to ring the alarm bell. This is not healthy! Sure, the Americans on top of the pecking order might show up at Party Conventions every four years and proclaim that ours is the freest country in the world. But many other Americans are simultaneously dying from their serfdom, whether they are aware of it or not.

For the time being, let’s consider freedom and equality neither friends nor enemies, but frenemies.