Credit: Javitomad

Which sort of judicial system, generally speaking, is more likely to lead to justice? One that:

- looks for the truth, or

- lets two sides fight it out to see who wins?

You might think that I’m setting up another facile thought experiment, but I am not. Most of the world has, through the fascinating and mysterious quirks of history, chosen one or the other of these underlying approaches to justice.

The first philosophy — justice as a search for truth — we call the inquisitorial system (because a judge sets out to inquire after the facts of a case, ie the truth).

The second philosophy — justice by duking it out until one side is left standing — we call the adversarial system (because two adversaries and their lawyers meet in court, and a judge merely makes sure that the rules are observed).

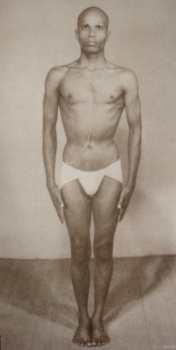

We generally find the inquisitorial philosophy undergirding the civil law systems of continental Europe and its former colonies and the countries that have adopted it voluntarily. That turns out to be most of the world — all the countries in blue on the map above.

And we find the adversarial philosophy mainly in the common law systems of England and all the lands it ruled at one point or another — ie, the countries in red or brown on the map. (Let’s leave the countries with Islamic Law, in yellow, and Mongolia, in green, out of this post.)

Because justice, and therefore law, is so fundamental to freedom (which is one of my favorite topics) I have for some time been pondering the question I opened with. So I challenged Richard, a frequent commenter on The Hannibal Blog and a veteran English lawyer, to compare the two systems. Somewhat to my surprise, he did.

In this rigorous series of posts, Richard introduces the systems in turn, proceeding methodically and cautiously to unveil — somewhat coquettishly, I might add 😉 — his preference. (I won’t spoil the fun: Go and find out for yourself.)

Here now is my modest contribution.

A brief history of the systems

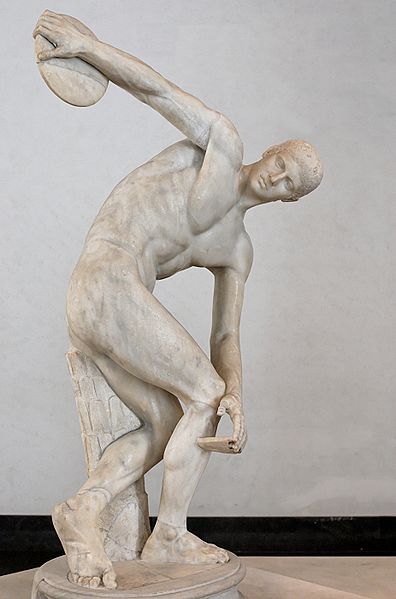

Historically, the adversarial system descends from the brute medieval practice of trial by combat.

You did me wrong! → Let’s fight.

It is, in short, the law of the stronger.

Click for credits

Right from the start, especially whenever ladies were involved, the adversaries were allowed to appoint champions to fight on their behalf.

Like its gruesome medieval judicial cousin, trial by ordeal, trial by combat made no pretense to truth. Somebody prevailed, that was all. So it was efficient. But we would not call that justice.

In 1215, Pope Innocent III wanted to change that. So he reformed the court system administered by the Catholic Church across Europe (ie, the ecclesiastical courts, from Greek ekklesia, assembly or church).

The idea was that an ecclesiastical court could take the initiative and summon and interrogate witnesses even without an accusation by one adversary against another.

Trial by combat was now forbidden in the ecclesiastical system. On the continent, this ecclesiastical tradition then became the basis for the subsequent evolution of secular courts.

But in England, Henry II had, during the 1160s, established parallel secular courts. When the church-administered courts in England switched to the inquisitorial system, the secular courts remained adversarial, and those in time became the courts of England. Hence the split.

Henry II

Critique

I) The adversarial system

The adversarial system makes me — intrinsically, philosophically, emotionally — uncomfortable because it was not originally designed to ascertain truth, merely the supremacy of one side.

That said, it has evolved in such as way that truth is now the implicit and desired by-product of the adversarial struggle. If the rules (of evidence, testimony, presumption of innocence et cetera) are sophisticated, it is hoped, the truth is revealed in the process and the “right” side wins, so that the outcome is indeed just.

Nonetheless, there are troubling remnants of the system’s combat origins:

1) The undue role of the “champions”

Today, we call those champions lawyers (attorneys, solicitors….). In the adversarial system, they are the stars. What do you tell a friend in trouble in an adversarial country? “Get a good lawyer.”

Some people try to get a good lawyer, but end up with a bad one, or at least one less good than the adversary’s. Other people cannot afford a good one. Others can afford entire armies of lawyers, and usually win. So money plays an unsavory role.

If the truth really wanted to be revealed, why should it matter so much which lawyer you have? But we all know that it does matter.

2) The undue emphasis on winning

An inquisitor wants to find the truth. But a prosecutor wants to win. To him, that means to convict.

A couple of days ago, I was chatting with Steve Cooley, the district attorney of Los Angeles County and a candidate for attorney general of California. How does he compare himself to his rival, Kamala Harris, the district attorney of San Francisco? Through the conviction rate, of course. Whether or not the convictions were just does not even come up for discussion. (How would you even discuss it?)

In practice, said Cooley, about 95% of convictions come through plea bargains, an inherent part of the adversarial system. (Ie, the two sides come to an agreement even before an independent judge or jury evaluates the truth of their arguments.)

Well, I recently mentioned Harvey Silverglate’s book detailing the various excesses to which prosecutors can go in the pursuit of victory. You can make anybody break down by piling more charges on him until he pleads. That does not make it just.

II) The inquisitorial system

The inquisitorial system makes me uncomfortable in a different way.

In theory, it is splendid to task somebody with inquiring after the truth. Take the example of plea bargains cited above: In the inquisitorial system, a guilty plea does not automatically lead to conviction. It is merely one more piece of evidence. (The inquisitor might decide to ignore the plea if he suspects, for instance, that the pleader is trying to protect somebody else, or is insane, et cetera.)

In practice, however, you have to choose an actual human being to find out the truth, and how is that likely to go?

There is a reason why we (or at least I) hear bad connotations in the word inquisition. It reminds us of the Spanish Inquisition, a time when the system went awfully wrong. The inquisitors, as it happened, were altogether more concerned with pleasing Ferdinand and Isabella than with ascertaining the truth. And they subscribed to the notion that you can get any truth that suits you; it’s just a matter of how you ask.

So an inquisition into truth can become corrupt. Notice, however, that this is a problem common to both the inquisitorial and the adversarial systems: The judiciary must be absolutely independent from political pressure. That includes not only the executive branch of government but also the mob. Ask black people in the Jim Crow South how well the adversarial system worked for them.

The subtler but more profound critique of the inquisitorial system has to do with what Richard calls “over-confidence in the expert”:

If you have a trained magistracy, ostensibly expert in discerning and charged with discovering the truth, there is the risk of over-valuing their work.

And why would that be a problem? Because experts are experts precisely because they have seen lots and lots of cases. And so they are likely to slip into a thought process that says “Hmm, this case X reminds of Y, and I should be consistent so I will…”. No. The facts (truth) of case X must be considered on its own merits alone.

Perhaps experts are less able to do that. As Richard says,

Justice is the art of espying the exception.

Which leaves us, unfortunately, where we started: with questions.

Who, expert or lay, is more likely to espy the exception? Who is most likely to be free and fair? Which process — a search for truth or a struggle that reveals it — is more just?