My last Facebook update said:

Too busy playing on Google+ to check FB

And that was five days ago.

The truth is that I’ve long been too busy doing anything to check Facebook. I’ve secretly, and increasingly, loathed Facebook since I joined it, which was relatively early (beginning of 2007, I believe), because my beat at The Economist back then was Silicon Valley, and it was simply part of my job to be fiddling with stuff like this. (I’m not the only one loathing FB, apparently.)

Ah, 2007. That seems like a distant era now. I still recall meeting Mark Zuckerberg, who was not yet used to meeting anybody, much less the heads of state and glitterati that surround him now, and who was awkward even by the standards of Silicon Valley’s skewed autism spectrum. (Here is the profile I wrote about him soon after that meeting.)

So anyway, I was and remained “on Facebook”, the way one just is. How could I not be? But I was almost entirely passive (observing incoming updates without sending outgoing ones). And I was proud of my wife, who is savvy in such matters and simply said ‘I’ll sit this one out’. She never signed up.

Why this skepticism?

Because Facebook is fundamentally (=unalterably) indiscreet.

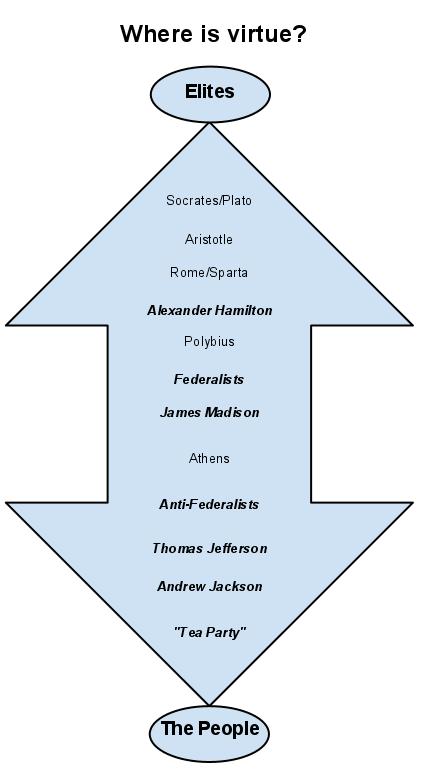

And it is fundamentally indiscreet because it is architecturally indiscrete. (Forgive me that word play.) Meaning: you cannot distinguish easily between different degrees of intimacy among the people in your social graph. The various relationships are not discrete, not separate.

Mark’s vision (as he told it to me back then, and as I described it in my early profile) was to be a “mapmaker” (like the heroic explorers of the Renaissance) of human connections. To him that was an algorithmic challenge. I always knew that his premise was unsound sociologically.

Tell me: In real life, how often do you walk up to somebody and request to be “friends”, then begin “sharing” pictures of your naked baby?

How wonderfully warm and fuzzy do you feel when somebody (oh yes, wasn’t he on my soccer team 30 years ago? Or perhaps I vomited on him at that keg party in 1989?) stops you on the street, asks to be “friends”, then shares his baby pictures with you?

Mark has been asking us all to do exactly this sort of thing. I thought it was strange back then, and I said so in our pages. (The picture at the top of this post is from that old piece.) But — did I mention? — that was in 2007. A different era, as I said.

Facebook then put us all on a roller coaster of “privacy” policies. (We’ve discussed some of them on this blog.) It got more and more confusing, and simultaneously boring. Who wants to put in the time to learn what Mark is up to now?

Plus: the page started to look like Times Square in the 1970s. (Remember, aesthetics really, really matter to me.)

So now we have Google+. It has not even officially been launched yet, but seems to have passed 18 million users today. We all thought that sheer fatigue would keep all of us from filling out yet another profile. But lo, everyone I know is already there, and we’re playing happily. Even my wife is trying it out.

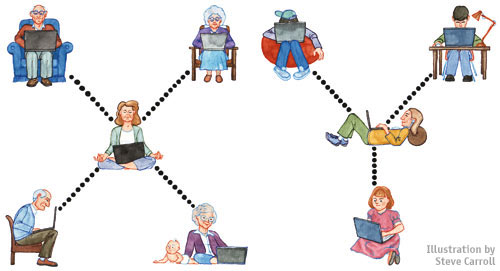

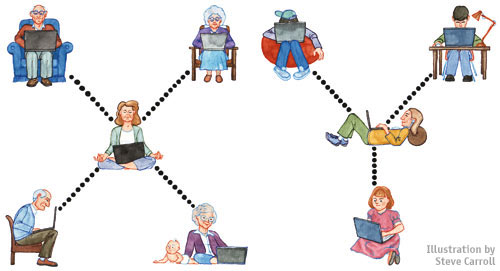

Google+’s crucial innovation (among many others existing or planned) is Circles. You can make as many of them as you like. They can contain 1 person, 2 people, the Dunbar number, or the entire web. Because there are things you want to share with just one person, or with 2, or with lots, or with everybody (as on WordPress).

Ergo: Discrete → discreet

You also don’t have to ask anybody to be your “friend”. Nor do you have to reply to anybody’s “friend request”. You simple put people into the discrete/discreet spheres they already inhabit in your life.

Quite a few of us — Nick Bilton at the NYT, for example — seem to be optimistic that this is the beginning of a good trajectory. (Nothing new should be evaluated by what it is today. What matters is what it will become tomorrow.)

Now, if you had asked me which company I considered least likely to come up with such a sociologically simple and elegant solution, I might well have answered: Google.

Its founders and honchos worship algorithms more than Mark Zuckerberg does. (I used to exploit this geekiness as “color” in my profiles of Google from that era.) Google then seemed to live down to our worst fears by making several seriously awkward attempts at “social” (called Buzz and Wave and so forth).

But these calamities seem to have been blessings. Google seems to have been humbled into honesty and introspection. It then seems to have done the unthinkable and consulted not only engineers but … sociologists (yuck). And now it has come back with … this.