Well, since Penguin Group (to which my imprint, Riverhead, belongs) has now made the cover jacket public, I figure I can, too.

I trust, as usual, that readers of The Hannibal Blog will not be coy about deconstructing it…

Well, since Penguin Group (to which my imprint, Riverhead, belongs) has now made the cover jacket public, I figure I can, too.

I trust, as usual, that readers of The Hannibal Blog will not be coy about deconstructing it…

The biggest social event of the year 1878 in Palo Alto, California, took place on a horse-breeding farm. Leland Stanford, former governor and co-founder of the all-powerful Southern Pacific Railroad, had retired and was indulging, here at the site where he would soon found Stanford University, in his passion, which was anything equestrian.

Stanford was, at a general level, an alpha male who trusted his own opinions. More specifically, when it came to horses, he considered himself “an expert”. So it was utterly clear to him that he, the expert, knew how horses galloped.

After all, all you had to do was look! And Stanford had looked, as had artists throughout all of human history. It was obvious that horses briefly “flew” by splaying their four legs in the air before alighting for the next leap. Like this:

So Stanford, as this account tells the tale, made contact with Eadward Muybridge, an eccentric Briton who had mastered the cutting-edge technology of the day, photography, and was able to take photos in rapid succession. Muybridge brought his kit to Palo Alto.

At Stanford’s invitation, large crowds turned out for the occasion. Muybridge was to document a galloping horse and thus prove common sense.

Eadweard Muybridge

Muybridge’s photos did nothing of the sort. Instead, they were shocking. For they disproved mankind’s common sense, thereby contradicting the direct observation of many generations.

You can see this disproof above, in the (deservedly famous) animation derived from the images. If you want to be sure, you can look at the stills in one of the other sequences:

During the only instant in the cycle when the horse is entirely in the air, its legs are actually tucked together, not splayed.

After Muybridge’s breakthrough, mankind thus had some adjusting to do, not least its painters:

Artists of the day were both thrilled and vexed, because the pictures “laid bare all the mistakes that sculptors and painters had made in their renderings of the various postures of the horse,” as French critic and poet Paul Valéry wrote decades later… Once Muybridge’s photos appeared, painters like Edgar Degas and Thomas Eakins began consulting them to make their work truer to life. Other artists took umbrage. Auguste Rodin thundered, “It is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop.”

(Does Rodin’s reaction remind you of anything today?)

The big point here is really that we should be less confident in (= more skeptical about — however you want to put it) our own opinions and grasp of reality. That’s because:

In that sense, this post is a follow-up on

This topic seems to strike a chord with writers and journalists in particular. The other day, for instance, I was discussing it with Rob Guth, a friend of mine at the Wall Street Journal. Rob recently wrote great stuff about the surprising recollections of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen (surprisingly negative about Bill Gates, in particular). As Rob got deeper and deeper into his research — meaning: as he “fact-checked” his sources’s memories of Microsoft’s early years — the “truth” became ever more elusive. Was so-and-so in the room all those years ago when such-and-such happened? A says Yes, he was. B says No. Suddenly A begins to doubt himself (re-narrating the story in his mind). And so on.

Journalists, of course, are not the only ones relying on the recollection or observations of others. Judges, lawyers and jurors do as well, to name just one particularly germane area.

In this article, Barbara Tversky, a psychology professor, and George Fisher, a law professor, suggest that eyewitnesses cannot always be trusted. (Since witnesses are at the heart of the adversarial legal system, this undermines our entire tradition of justice.)

As Tversky and Fisher say,

Several studies have been conducted on human memory and on subjects’ propensity to remember erroneously events and details that did not occur. …

In particular,

Courts, lawyers and police officers are now aware of the ability of third parties to introduce false memories to witnesses…

But even without such tricks,

The process of interpretation occurs at the very formation of memory—thus introducing distortion from the beginning. … [W]itnesses can distort their own memories without the help of examiners, police officers or lawyers. Rarely do we tell a story or recount events without a purpose. Every act of telling and retelling is tailored to a particular listener; we would not expect someone to listen to every detail of our morning commute, so we edit out extraneous material.

In fact, these studies show what Rob discovered during his interviews of sources for the Paul Allen story:

Once witnesses state facts in a particular way or identify a particular person as the perpetrator, they are unwilling or even unable—due to the reconstruction of their memory—to reconsider their initial understanding.

Tversky and Fisher conclude:

Memory is affected by retelling, and we rarely tell a story in a neutral fashion. By tailoring our stories to our listeners, our bias distorts the very formation of memory—even without the introduction of misinformation by a third party…. Eyewitness testimony, then, is innately suspect.

And:

It is not necessary for a witness to lie or be coaxed by prosecutorial error to inaccurately state the facts—the mere fault of being human results in distorted memory and inaccurate testimony.

A while ago, I had a little email exchange with one of my editors in London (The Economist’s HQ). I had written an article and the question was whether or not I should also write a Leader (ie, an editorial). In other words, should The Economist, through my words, opine, and how exactly?

The editor wrote to me:

I was very intrigued by the idea, and there was a lot of interest in the meeting. The problem is the prescription. I think you’re inclined to [subject omitted]; but I’m not inclined to go as far as that….

As you see, I excised the actual topic of discussion, because it is utterly irrelevant to my point here. Here is what I replied:

I’ve actually (as usual) got no clear “prescriptions” in my mind at all. I just made up some stuff to pitch a Leader outline to you. I’m always surprised by how interested we at The Economist are in our own opinions. Personally, I’m 99% interested in understanding the problem, and quite flexible in the other 1%…

Because the editor and I know each other well, I knew my cavalier tone would not be misunderstood. (In the end, there was no space in that week for that Leader anyway.) But then I realized that my point was perhaps more fundamental. How so?

You know you’re in trouble when somebody begins a monologue with “There are two kinds of people…”. But we might indeed stipulate that, yes, there are two kinds of people: searchers and preachers. You might even consider them Jungian archetypes (about which we haven’t talked for a while).

The preacher:

The searcher:

And yes, of course, we’re all a bit of both, but in different proportions. Personally, for once, I’m not that confused about what I am: a searcher.

Which is to say: I have lots of opinions, but the opinion I’m proudest of is my opinion about my opinions. Generally, I’m quite suspicious of them. I interrogate them, and they answer back. Fascinating conversations.

Quite a few of us at The Economist are, individually, searchers. And yet, The Economist itself, as a whole, is clearly in the preacher camp. An interesting point to ponder.

It’s been an exhausting but satisfying and edifying week. I spent all of it speaking, rather than writing, and I learned a lot about the difference.

The occasion was my Special Report on “Democracy in California”, which was on the cover of the previous issue of The Economist, a cover as cheeky as one might expect of us (see above). The cover of the actual report (which is an insert of 11,000 words, eight chapters) looks like this:

It’s my fifth Special Report (we used to call those things “Surveys”). I usually urge people to read a Special Report on paper, or as a PDF, because it is really one single narrative, with each chapter leading to the next and none meant to be read in isolation. Online readers often land on one chapter and don’t realize it is part of something bigger.

Here are the chapters:

I tried to remember and list all the sources here, but it’s inevitable that I forgot somebody, so apologies.

Once the report was published, two of my colleagues — Amy Jaick and Dayna De Simone, our brand enhancement geniuses — ferried me around California to “market” the report.

As you might remember, I’ve long been pondering the difference between the written and the spoken word, so it was constantly on my mind this week. The two are really completely different. You can write well but speak awfully, or speak well but write awfully. (You can also be good or bad at both, of course).

All of which is to say that this was really a great warm-up for the speaking I’ll probably be doing in January when my book comes out.

In particular, I now appreciate the importance and difficulty of being a good “accordion”. Which is to say: You have to be able to expand and contract at will — ie, to speak equally well about (in this case) all 11,000 written words in

And that takes quite a bit of practice, especially since I don’t believe in using any written notes at all.

The only reason, as far as I can tell, why somebody might want to hear a writer speak (as opposed to just reading his writing) is spontaneity, which equals authenticity. If you’re speaking from written notes, how can you be spontaneous? Whenever I’m in an audience and a speaker uses written notes, the oratory is dead and boring.

So I speak “naked”, as it were, which can, admittedly, be a bit nerve-racking. I did get sidetracked a couple of times. But as the week went on I got better at my pacing. Every talk was partly the same and partly different, and Amy and Dayna gave me great feedback on what worked and what didn’t, so that “the speech” kept improving.

And the reaction from the various audiences was fantastic. At every event, we ended up having a lively debate. I was learning a lot from the audience. And learning is really my main hobby. So I guess it was a good week.

So I have them: the full title and the publication date.

(In fact, one of you has beaten me to it and found the nascent Amazon entry before I even knew it existed.)

Title:

Hannibal and Me: What History’s Greatest Military Strategist Can Teach Us About Success And Failure

Date: January 5th, 2012.

Yes, yes, I know that date seems rather late. What can I do? My publisher tells me that it was strategically chosen as the perfect time for this sort of book. So there.

Regarding the title: It’s quite ironic that my very first post on The Hannibal Blog, all the way back in summer of 2008 (my god, have I been at it this long?!), explained why Hannibal and Me is not the title. And now, it’s … the title after all.

Anyway, I’ll show you the jacket design soon. But feel free to weigh in on the title, from the gut.

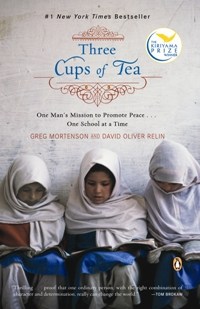

Like many of you, I’ve been following, with shock and amazement, the tale of Greg Mortenson, the author of Three Cups of Tea.

Like many of you, I’ve been following, with shock and amazement, the tale of Greg Mortenson, the author of Three Cups of Tea.

If 60 Minutes is correct (and with allegations such as these, the target deserves the benefit of the doubt), then Mortenson fabricated much of his best-selling book.

But then I remembered this talk by Chris Chabris, a neuroscientist, in which he talks (starting at minute 5) about “the illusion of memory.”

In brief: We trust our memories, but we shouldn’t, because many of them are wrong. The human brain reconstructs the past by telling stories (an extremely familiar idea here on The Hannibal Blog), and it does so by conflating different events, people, times and anecdotes. So when politicians (among others) seem to “lie” about their past (remember Hillary Clinton dodging sniper fire in Bosnia?) they are probably making honest and all-too-human mistakes of memory. (Whether this applies to Mortenson, I have no idea.)

In brief: We trust our memories, but we shouldn’t, because many of them are wrong. The human brain reconstructs the past by telling stories (an extremely familiar idea here on The Hannibal Blog), and it does so by conflating different events, people, times and anecdotes. So when politicians (among others) seem to “lie” about their past (remember Hillary Clinton dodging sniper fire in Bosnia?) they are probably making honest and all-too-human mistakes of memory. (Whether this applies to Mortenson, I have no idea.)

In any event, as I was watching the 60 Minutes report, a fear suddenly struck me. What if I myself misremembered anecdotes in my own book? (To be published, as it happens, by Riverhead, which is part of Penguin, which also owns Viking, which published Three Cups of Tea.)

So I thought of the personal bits in my book. There aren’t that many personal memories — most of it is based on history and biographies, with sources. But there are some. For instance, there is a part where I recall burrowing through the dusty shelves of the library at the London School of Economics, in 1994 or 95 when I was a graduate student there, and finding, to my considerable surprise, a book that turned out to be the PhD thesis of my father. I remember how the book cracked as I opened it, and I recall noticing that nobody had ever checked it out.

Never mind why I told that little anecdote in my book (it makes sense in the context). Suddenly I was afraid whether this was in fact how it happened. Was it there, at the LSE, where I found it? Or perhaps at the nearby University of London library? Or perhaps around that time at some library in Germany? Does the LSE library even have the book? (That would be very embarrassing.) If I did find it there, is it true that nobody had ever checked it out? Was the cover grey, as I recall? Had I just dreamt the whole damn thing?

So I fact-checked my own memory.

Fortunately, the LSE library does have the book, as can nowadays be ascertained online. What about the rest?

So I called the library. I expected a phone tree. There was none. Somebody named Andy Jack answered.

Having spent years in California, I have learned never, unprompted, to attempt irony or humor because that can fall so utterly flat in America. So I was bracing myself for a long and complicated explanation and an awkward request for help — in short, a conversation as pleasant as calling, say, an American health insurance company.

Instead, within seconds, I was reminded of my old world over there: For Andy was, of course,

I barely got out three or four words (alumnus … book … Three Cups of Tea… anecdote…) when he understood.

His reply came in a tone that contained … irony. Very subtle, just a nod, really. At once, I knew this was going to be easy, unAmerican.

At that instant, I realized that he was already walking up the stairs. Whither? To the shelf! Before I knew it, he was holding my dad’s thesis in his hands and confirming my memories.

What a relief. I had remembered everything correctly. The cover is blue now, but that’s because the book literally fell apart at some point and had to be rebound. Andy told me it has 164 pages, plus 22 more of references. My dad’s name is in gold. It has indeed never been checked out, at least not since they changed computer systems, which was after my time. But it has no barcode :), so it could not have been checked out!

Andy, by this point, took pride, you understand, in making an anecdote in a book — my book, unpublished and completely unknown to him — correct and good. If you’re reading this, Andy, thank you.

I know, I know. You’re at the edge of your pew. What was my dad’s book about?

Why his PhD thesis, published in Bonn in 1967, was not an international bestseller, nobody knows. Its sex appeal is obvious. The title is:

Probleme einer allgemeinen aussenhandelspolitischen Liberalisierung

That means something like: Problems with a general liberalisation of international trade

I divulge this reluctantly, because you may pounce on the copy, spread the meme virally, and we all know where that might lead for my dad: Sudden fame, groupies, temptation, trashed hotel rooms, my mom destabilized.

The regulars among you might already have made a few other connections:

Where have I been, you may have been wondering. Well, this chart above shows you where I’ve been. I used to take my coffee breaks blogging, but for the past month I’ve been taking them (ie, a couple of 10-minute breaks a day) at the Khan Academy, which is the subject of this post.

The chart shows my time logged watching chemistry-lesson videos during the past month. (Notice that I’ve earned some meteorite badges, and even a moon and an earth badge. 🙂 This boy — his name is Sal Khan — knows how to motivate kids of all sizes.)

Now, you too should care about this (ie, the Khan Academy), and I am about to tell you why. But first…

I don’t know how it’s possibly that I only discovered the Khan Academy last month, but that’s what happened. And I discovered it because Dafna, a frequent commenter here on The Hannibal Blog, mentioned it in passing, apropos of something else, and I clicked through and was hooked.

Dafna: You get more than a fist bump, you get a chest bump or body flop. Now…

I used the word revolution in the title of this post, so please indulge me in another brief tangent, concerning that word.

I can’t tell you how sick I am of it. And the verb, to revolutionize, is even uglier. Practically every PR pitch I get in my inbox (and I get many) announces that something or other is being “revolutionized”. How yucky. And how ludicrous.

By definition, revolutions are extremely rare in human history. I myself have, as a journalist, proclaimed precisely one revolution in fourteen years (and that was the ongoing media revolution, which I put on a par with the Gutenberg printing press.)

So I don’t use the word lightly. But I think there is a revolution underway, and it is in learning. So now I might have your attention.

I was tempted to summarize it here, but why would I distract from Sal Khan explaining it personally? So watch this talk below, and then come back here to read the rest of the post:

Now that you know what Khan Academy is, you’re ready to contemplate what makes it (or things like it, such as future iTunes U courses et cetera) revolutionary.

A revolution is technically a circumnavigation of something (as that of our planet around the sun). But we usually think of it, in human affairs (the French Revolution, say), as a rotation, a turning upside down of something.

This is what Sal thinks Khan Academy can do to education as it is traditionally practiced in schools.

In this piece in the Wall Street Journal, he argues that Khan Academy can

“flip” the traditional classroom: Students can hear lectures at home and spend their time at school doing “homework”—that is, working on problems. It allows them to advance at their own pace, gaining real mastery, and it lets teachers spend more time giving one-to-one instruction.

Ponder this for a while. And then you see why this might be revolutionary.

On a personal note: Sal, with his approach, epitomizes a lot of my own worldview. He:

In due course, you will hear more, much more, from me on this subject.

It was only a matter of time, I suppose, until I had to advance from venting about the evils of distracted driving here on The Hannibal Blog to doing so in The Economist. So here it is. My rubric says it all:

Distracted driving is the new drunk driving.

The research and writing process had the usual frustrations (usual for The Economist, I mean): I talked to lots of people, read many tens of thousands of words of academic research, took more than 10,000 words of notes, and then…. reduced it all to 700 words.

Oh well. Out went a whole lot of nuance.

If you ask me to name the most interesting concept from the article, and about the whole topic, it is this:

The human brain cannot process communication (oral or written) with a person who is not physically present without drastically reallocating attention and thus compromising driving safety. This is a biological fact. All those who claim that they can call/text and drive are the modern equivalents of the people you might (if you’re older) recall bragging that “I can hold my liquor” before that started sounding ridiculous.

As Satoshi Kanazawa, an evolutionary biologist and a delightfully belligerent blogger, puts it:

Any communication with parties who are not immediately present is evolutionarily novel, and the human brain is likely to find it cognitively difficult to handle.

Steering a large metal weapon at lethal speeds through crowded surroundings, of course, is also “evolutionarily novel”. So we have a double whammy. Homo sapiens just didn’t do this stuff in the savannah.

And yes, this means that bluetooth (“hands-free”) does zero to reduce the risk.

Anyhoo, here is just a tiny sample of some of the research that, sadly, got little or no exposure in my article for lack of space:

If you’re like me, you’ve been following with great concern the latest radioactivity measurements in various places, from Japan to the US West Coast. What an utterly hopeless task:

Is this a joke? How are you supposed to understand anything at all from this gibberish?

Well, yes it is a joke, of course, in the same way the entire universe is a joke (and a rather sick one!), as the apocryphal sage Murphy first observed:

Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.

I once saw a booklet of addenda to Murphy’s Law. This week, I suddenly remembered one that seems germane:

Measurements will always be given in the least useful unit: Thus speed will be given as furlongs per fortnight.

Fortunately we have Mr Crotchety, who sent me this chart which, if correct, puts it all in some perspective.

Amateur writers often make the mistake of not cutting out their own “throat-clearing” in the first couple of paragraphs.

What is throat-clearing? It is what we in the biz sometimes call the verbiage that most ordinary people seem to consider necessary prologue before they say anything of consequence. “Laying the ground”, “setting the scene,” and so forth.

90% of the time, any piece of amateur writing can therefore be improved simply by lopping off — wholesale and mercilessly — the beginning. Somewhere in the text, the writer does have a point to make, and that‘s the place to start.

(Somehow, the amateur writer himself usually cannot find that place.)

Professional writers might have the opposite problem: they often don’t know when to stop. Or perhaps they do know when to stop, but someone or something forces them to go on just a bit longer. And thus they ruin fantastic texts with banal or ridiculous “conclusions”, “summaries”, “recommendations” or other thought detritus.

David Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism at Rutgers University, makes this point in an amusing essay by using lots of famous books as examples.

How often, he says, some weighty, riveting, stirring text (we are mainly talking about socially or politically aware non-fiction) comes to ruin in its last chapter because

no matter how shrewd or rich its survey of the question at hand, [it] finishes with an obligatory prescription that is utopian, banal, unhelpful or out of tune with the rest of the book… [No] one, it seems, has an exit strategy… [and] hard-headed criticism yield[s] suddenly to unwarranted optimism…

When politicians, whether aspiring or recovering, produce such drivel, we might not be surprised. Of course somebody like Al Gore might develop a good argument that evidence and logic have been driven from public debate (The Assault on Reason), and then conclude that

I feel more confident than ever before that democracy will prevail.

But when real writers do this sort of thing, it is a genuine pity. So why do they do it?

Greenberg thinks that

One reason is that editors expect them. The journalist Michelle Goldberg conceived her first book, “Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism” (2006), as a work of reportage on a subculture of growing political influence. She hardly felt qualified to lay out an agenda for curbing the power of the religious right, but “one of my editors insisted I do it,” she recalled in a recent interview. Inevitably, reviewers called her on it…

In other cases, he thinks

authors have themselves to blame. Having immersed themselves in a subject, almost all succumb to the hubristic idea that they can find new and unique ideas for solving intractable problems. …

And me? Some of you may recall the little game I played for about two years with my own editor at Riverhead. He kept pressing me to add a final chapter of “lessons”. I kept demurring.

In the end, he won. Ie, I did add a chapter of lessons. As it happens, I surprised myself by liking that chapter. (It’s instead my second chapter that I like least and worry about most.) Who knows. I might already have fallen prey to Greenberg’s hubris. Fortunately, the book will be out soon, and all sorts of reviewers will volunteer their honesty with the requisite brutality.