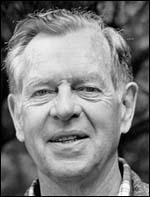

Joseph Campbell

A follow-up to my my post on why truth is in stories: Many of you know about this fascinating theory that there really is only one story, which we tell one another again and again in infinitely many variations.

This is the so-called Monomyth, which I prefer to call the Ur-Story.

The man who popularized the idea is Joseph Campbell, whose book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, is naturally on the bibliography of my own book.

To simplify his idea, it is that the same fundamental plot and character types and experiential vocabulary underlie all major myths and movies and novels and, well, stories. From Odysseus to Jesus and the Buddha, from Navajo stories to Chinese ones, from ancient tales to modern ones.

An archetypal hero of some sort receives a call to adventure, often refuses the call before accepting it, sets out on a quest, crosses various thresholds, overcomes adversity and trials, encounters a woman as temptress, atones with his father, obtains a boon to society and attempts to return and bring it back. And so forth.

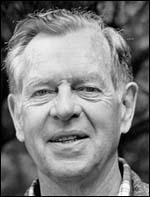

Carl Jung

Campbell was influenced by James Joyce, but the bigger credit, in my opinion, goes to Carl Jung. It was he who came up with the concept of archetypes (which I use in my book). The Hero, the Child, the Great Mother, the Mentor, the Wise Old Man, and so forth.

All this may strike you as odd. Aren’t there infinitely many stories, one for each person? Well, no. There are infinitely many variations and twists. But one fundamentally stable storyline.

This idea has wormed its way into conventional wisdom now. I was chatting about my book with my friend Evan Baily, a teller of children’s stories in film. Evan said that story is always about character, and how pressure is brought to bear down on him until he breaks down or reveals himself. Evan pointed me to Robert McKee’s seminars on story-telling, famous in Hollywood and beyond. Ultimately, this is all about the Ur-Story.

What’s most wonderful about all this is that we never get tired of hearing the Ur-Story. Telling and hearing it is about being human. And we all get to tell our variation of it. Which is why I’m writing a book.