Life, or history, is a tragicomedy. A lot of it is is just plain absurd. Hilarious, if it were not also terrible. The epic is bound up in the banal, the heroic in the vulgar. Wars are started out of folly or oversight, or somebody’s vanity, or pure mistake.

Let me give you an example from the era that forms the backdrop for the main characters in my forthcoming book. This is the giant cock-up that led to the Punic Wars, stretching over 118 years, robbing the ancient Mediterranean world of entire generations of its young as the the World Wars of the 20th century once would, and ending in the complete annihilation of Carthage.

To recap: Last time in this series we left off with Pyrrhus, the studly Hellenistic king who fought the Romans, usually winning (but hey, those Pyrrhic victories) but finally acknowledging that those Romans, so obscure and backward until now, were quite something. He went home and left Italy to them. For the first time, the Romans were now all the way down in the Italian “boot”, looking over at Sicily (see map).

Sicily, remember, was a mostly Greek island whose western parts Carthage, the maritime superpower of the day, considered to be in its sphere of influence.

We have already reviewed how Carthage and Rome were twins in some ways, friends in others. But now suddenly, they found themselves staring across the narrow straits of Messina, then called Messana. What would happen next? Did anything at all have to happen next?

No, nothing had to happen. That’s just what historians pretend 2,000 years later when they need to get tenure. Instead, here is what did happen:

Meet the Mamertines

There was this band of hoodlums–hooligans, gangsters, goons, whatever you want to call them. They were from southern Italy but went to Sicily at some point to look for work. Sort of like the Okies during the Depression. They found jobs in the great Greek city of Syracuse for a few years, but then got fired. So they wandered off again.

But on they way back to Italy they stopped at Messana, also a Greek town. The town’s elders, always good hosts in the Hellenistic way, gave them lodging. The hoodlums said Thank You, waited till everybody was asleep, got up and cut their hosts’ throats. Then they took their women. Then they declared that Messana was now theirs.

For good measure, they called themselves Mamertines, or “sons of Mars”. Looks better in the history books.

They kept being hoodlums, ransacking the towns in their neigborhood, until the Syracusans heard about this and sent an army. Yikes, the Mamertines thought. We better call for help.

So they contacted the Carthaginians in the west of Sicily and invited them over, just to show some force and scare the Syracusans off. The Carthaginians came, and the Syracusans thought it better not to risk a war over, well, hoodlums. (They knew whom they had recently fired, after all.)

Except now the Mamertines thought ‘Yikes, those Carthaginians are a bit scary too, aren’t they?’

So–and I think you see where this is going–they contacted the (wait for it) Romans, who were, after all, just a stone’s throw across the straits, in Rhegium (also Greek), today’s Reggio.

Sure, the Romans said. Why don’t we hop over and strut around a bit. We kicked out Pyrrhus, after all.

The Carthaginian commander thought it best not to risk a full-fledged war over, well, hoodlums, and left. But this was picked up by the Carthaginian equivalent of Fox News and the superpower decided that it had been humiliated. It crucified the general. (Literally, by the way.) Then Carthage sent a force to drive the Romans back across the straits.

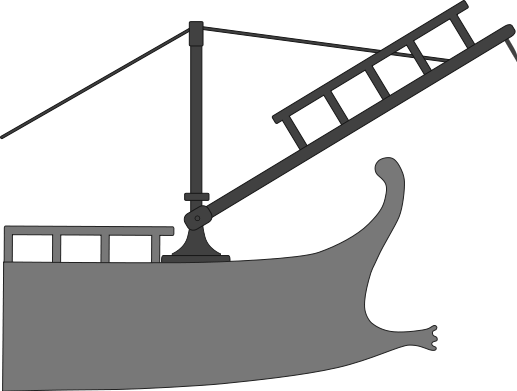

And this, in 264 BCE, is how it started! The First Punic War would last 23 years. It would see some of the greatest sea battles of all time, including our own. It would be followed by the Second Punic War–Hannibal’s war–which was even bloodier. And then by the Third Punic War, which was genocide.

And the Mamertines, you ask?

Good question. Somehow they vanished from history the moment they entered it. We have no idea where they went or what became of them. The Romans, the Carthaginians, the Sicilians–nobody heard about them again or cared to inquire. After all, they had just been a bunch of hoodlums, passing through.