What if we could get together to form a new kind of society … and we did not even know who we would be in that society?

This is a famous thought experiment, proposed by the Harvard philosopher John Rawls in his 1971 book, Theory of Justice.

Rawls was trying to justify democracy as fair as opposed to merely utilitarian (ie, “the greatest good of the greatest number”). How would we go about deciding what is fair? By imagining a situation that has never existed, and indeed can never exist.

Rawls called that situation the “original position”:

No one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does anyone know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like. I shall even assume that the parties do not know their conceptions of the good or their special psychological propensities. The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance.

You have probably already grasped the power of the experiment. Normally, we think of justice with ourselves in mind. A single black mom in a public-housing project will have a very different view than a start-up entrepreneur in Silicon Valley or a trustafarian in prep school or a prisoner or …. you get the point.

But if we don’t know whether we will be tall or short, male or female, smart or dumb, lazy or ambitious and all the rest of it, we have to test every principle against the possibility that we might be the least advantaged member of society with respect to it.

A simple example: Slavery in 19th-century America.

Slave owners considered America free and fair and were prepared to go to war for that “freedom”. That’s because the slave owners assumed that they were, well, slave owners. Using purely utilitarian reasoning, they might have concluded that slavery produced the maximum pleasure of the greatest number of people (ie, the white majority) and was therefore right.

But if they had played Rawls’ thought experiment, they would have had to imagine that they might instead be slaves. Suddenly, slavery no longer looks so good.

Getting liberté, egalité, fraternité onto one flag

Now, some of you might remember that, back in April, I tried to figure out whether freedom and equality could ever coexist, as the naked-boobed Marianne (pictured) was clearly hoping. In that post, I was thinking about biology. But perhaps the answer lies in Rawls’ thought experiment.

As we imagine a society without knowing what role we have in it, we will certainly agree that it should be free, and that we should not sacrifice that freedom by forcing everybody to be equal.

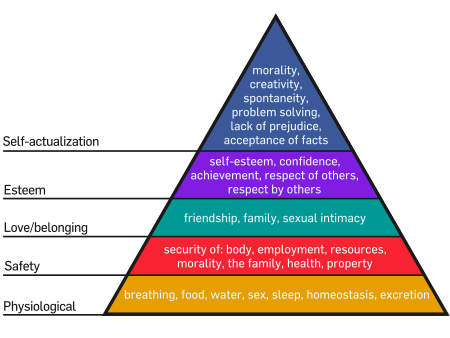

But that leaves us having to imagine inequality, and, thanks to our veil of ignorance, we might be the ones ending up with the least (wealth, opportunity, beauty, power…). So how can we agree to inequality that is fair?

The answer is

- First, that inequality must benefit even the least advantaged member of society (though obviously not in the same proportion). So we do not mind that the Sergey and Larry at Google get astronomically rich because even a single black mom in a public-housing project can now google where to get her baby a flu shot.

- Second, that the cushy positions in society must be open to all.

Intelligence and talent, for those playing the thought experiment rigorously, would thus cease being mere boons for the individuals that are lucky to have them and instead become social resources that help even those who don’t have them.

I can immediately think of lots of things that we still would not agree on–inheritance taxes, say. But Rawls’ thought experiment definitely introduces even a certain amount of fraternité into the equation. Marianne would love him. For the power of this experiment, I’m hereby including Rawls in my pantheon of great thinkers.