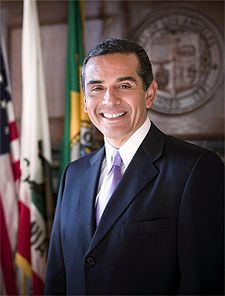

Antonio Villaraigosa

I met Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa for the second time the other day, and he did something peculiar — also for the second time, thereby making it notable.

He brought up fathers.

You may recall that I’ve pondered the role of fathers in success when reflecting on Obama and McCain, or Bill Clinton and Gavin Newsom.

The theory, to remind, is that (male?) leaders often have absent fathers.

So here is what Villaraigosa did to make me think about that again:

First time

I first met him last summer, when he was still being talked about as a possible Democratic candidate for governor. He is the first Latino mayor of LA since the 19th century and a wily politician, so he was said to have a chance. On the other hand, he had a new sexy girlfriend who was not his wife and so forth, so perhaps not.

So I went into his office in City Hall. He looked tired, with bags under his eyes. I thought that his face was right out of The Godfather — in a good, soulful way — but his hands were small and soft.

He surprised me by insisting on first talking about me. I didn’t quite know how to handle that. But he wanted to know a whole lot about me — what schools, where from, etc. He said he liked the boots I was wearing. I realized that he was a people politician (in fact, I kept getting distracted by all the photos of him with famous and beautiful people), not an ideas politician.

So we started talking about what I talk about: ideas. I thought it was slow and plodding. Then I realized that he slowed down for me whenever he thought he was saying something sound-bitey, so that I might transcribe it more easily.

But then finally we found a topic that got him relaxed and enthusiastic. Ostensibly, it was his city, LA, which is so fantastic. But here’s the reason why it’s so fantastic:

People don’t care who your father is.

He said that several times. As in: In New York, you need to be from the right family, but here we only care about what you are today.

Or perhaps as in (I imagine his thought bubble): My father left my mom and me when I was young, so screw him.

He did, in fact, say that he had seen his father at most 25 times in his whole life, making it clear with a (perhaps exaggerated) gesture that he couldn’t care less about him.

Second time

I met him again a few weeks ago when my editor was visiting me and I took him around to see interesting people. This time, Villaraigosa looked much better. No bags under his eyes. He was no longer a candidate for governor, so now he was just enjoying himself as mayor (and in his private life).

Again, I got distracted by all the photos of him with famous and beautiful people — they were now on automatic slide show on a large electronic picture frame.

Again, the slow and deliberate sound bites about weighty topics. Again, name-dropping (he also knows some British politicians, and he wanted us to know that).

Then my editor and I said Thank You and left. We were already in the hallway, and Villaraigosa huddled with his handlers for the next meeting.

Suddenly, Villaraigosa ran out and after us, all but screaming:

You know what? Screw it. Let’s do a story on how great LA is. The greatest city in America.

He was beaming with excitement:

I mean, here nobody cares who your father is!