[picapp src=”a/0/e/0/d5.jpg?adImageId=7132613&imageId=2039813″ width=”500″ height=”351″ /]

Here is an admittedly tiny and prosaic example of a big and poetic idea–the idea in Kipling’s If and in my book that disaster can be an impostor (as can triumph). The disaster in this case is more of a nuisance, but you will get the point.

1) The nuisance

My (youngish) Mac Book Pro has had a boo-boo. The screen started going black (why do “screens of death” have to be blue anyway?).

I happen to be in the Apple elite, equipped with all sorts of plastic cards (Apple Care, Pro Care….) that allegedly bestow privilege upon me. So I went to the Apple Store, itself famous for allegedly being at the cutting edge of retail savoir-faire, to get the laptop fixed. I brandished my cards and, after a stressful wait, succeeded in persuading a helpful staff member to …. schedule an appointment, two days hence, for me to come back and get my laptop fixed.

Two days later, I dutifully returned (traffic, parking garages….) to the famous store. Another stressful wait. Somebody took my laptop. The next day, they called to say that they needed another part (the RAM). They called again two days later to say that they needed yet another part (the logic board). Then they left a voice mail (Apple’s iPhone, which I also own, had not rung as it ought to when a call comes in) to say that it would be faster (sic) to send the laptop to a distant part of the country where logic boards are more plentiful, but that they needed my approval. I called back, but they had left for the day.

I called again the next day–at 10AM, when they start work–and gave my approval. The laptop, I was told, would now be en route “from 5 to 7 days”. This was 5 days after my original visit to the famous store with my fancy cards. My lap has been, and remains, untopped.

2) Why I expected this to be a big deal

I am a nomadic worker, and my laptop in effect is my yurt, or office, and thus one of the two West Coast Bureaus of The Economist (the other bureau being the laptop of Martin Giles in San Francisco, who replaced me in my previous beat). So I assumed that no laptop meant no bureau, no articles, no work. I assumed this because this was my experience in 2005, when another laptop of mine died.

3) Why it’s not

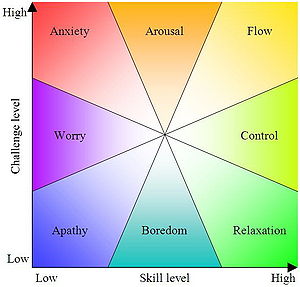

But things have changed since 2005. Something called “cloud computing” has come along, diagrammed above. It’s an old idea newly implemented: that information and intelligence reside in the network, to be accessed by “appliances” or “terminals” which we nowadays call web browsers. If you use web mail, Facebook, WordPress, Flickr, YouTube etc etc then you are computing in the cloud. You are not longer storing and crunching data in the machine on your lap. Instead, you are doing it on the internet.

After my previous laptop disaster in 2005, I began to train myself (I am a technophobe by nature) to start using the internet instead of perishable machines. Gmail, Google Calendar (which I share with my wife and a few other people), Google Reader, Facebook, and so forth.

Slowly, I started migrating more and more activities into the cloud. This was slow because of inertia. But I kept at it. My phones (Skype and Google Voice) are now online, as are many of my photos.

So it occurred to me, before going back to the Apple Store, to complete this process. I put all of my current or important documents on Google Docs. This was surprisingly quick and easy. I had never understood why I was using Microsoft Office in the first place, since it was bursting with features that I never use and that confuse me.

Now, instead of emailing my editor a Word doc, I “share” a Google Doc with him.

So now my digital life is entirely in the cloud. As some of you have noticed, even though I have not had my laptop, I have been “on”. Nothing has changed. I use my wife’s laptop, or somebody else’s, or my iPhone, which is almost as good. I no longer really care about my laptop.

4) Progress = Bye bye, Steve, bye bye Bill

At some point, I may yet get my snazzy Mac Book Pro back from this famous Apple Store. Will I care? Enough to go to the store one more time to pick it up. Barely.

The truth is that this slight nuisance, this mini-crisis, nudged me to do what I should have done long ago. It forced me to liberate myself from Microsoft’s software and Apple’s hardware, neither of which I need any longer. Yes, there are some new vulnerabilities (there always are). But I am, if not free, a lot freer.