Almost twelve years ago, when I joined The Economist, a kind and well-meaning colleague pulled me aside for an introduction to our culture. I had naively asked about an internal power struggle that had occurred many years before but involved some people who were still around. “Ah,” said my conversation partner, in a wry British way,

that’s when the Roundheads won the day.

“The what?” I asked.

Another colleague had overheard us and now joined in, closing the door to the hallway.

It doesn’t concern you, Andreas, because you’re not English. But it’s about Roundheads and Cavaliers.

You see, The Economist, being British–indeed English–has these two types within it, and out of this changing mixture comes the cocktail that is our culture.

I think my colleagues were wrong that this only concerns Englishmen. If you read on, I think you’ll agree that there are Roundheads and Cavaliers among, and inside, all of us.

Some historical context

The terms Roundhead and Cavalier go back to the English civil wars in the 1640s.

On one side were the parliamentarians, who wanted to get rid of the king. They were:

- Puritan

- angry, dour, outraged, earnest.

- for Cromwell

- a tad humorless

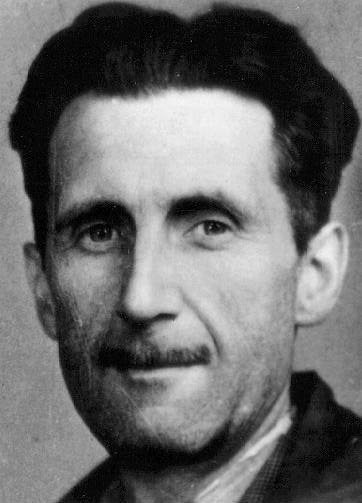

They also, at least in the beginning, liked to dress plainly and cut their hair short, which made their heads appear, at least to the other side, “round”. So their opponents called them Roundheads. Here is a good portrait of one:

On the other side were the royalists, who wanted, as the name implies, to keep the king. They were:

- anything but Puritan, and indeed rather good at indulging

- rather less good at being outraged, thanks to a certain inbred nonchalance

- against Cromwell

- flamboyant in style, and always ready to wink and chuckle at the insanity of it all.

Here is a good portrait of one (by the great Frans Hals):

I think you get the point. I mean, you must get the point. Just look at them.

Fast forward to today

Let’s not dwell on how the king lost his head and all that; these things happen. The reason these terms endured, at least in the English upper class, is that they describe types, and possibly archetypes.

The English brought these types to America. They sent the Roundheads to Massachussetts and the Cavaliers to Virginia. Both strands are still alive in America today. But the Roundheads won. Individual Americans may be one or the other, but American culture as a whole is reliably Roundhead:

- earnest, literal

- always ready to be outraged and indignant

- not naturally given to irony

By contrast, in old England, and at The Economist in particular, the balance has tilted slightly toward the Cavaliers. These are cultures of irony, in which too much outrage and earnestness is, well, unseemly. (And yes, I think that’s why so many American Cavaliers like to read us; their home press makes them feel lonely, we make them feel at home.)

Add: subtlety

At this point, a number of you may be preparing to be, ahem, outraged. So let me introduce some nuance and preempt some misunderstandings (there’ll be a few anyway).

First, this is not about Left or Right. It’s about temperament. Let’s just take some examples from the right side of the spectrum:

| Roundhead | Cavalier |

| Thatcher | Heath |

| DeLay | Reagan |

Second, it’s not either/or, whether in individuals or cultures. Rather, I think that Roundhead and Cavalier relate roughly as Yang and Yin do:

But, just as each of us is somewhat more Yang or more Yin, each of us also tends to be more Roundhead or Cavalier.