I ended the previous post, the first in this series on Socrates, by suggesting that we “count all the other ways in which Socrates, like Hannibal, is relevant to us, today.” So let’s start with perhaps the most important (if not the most famous) insight that Socrates gave us: the incredible importance of knowing good from bad conversations. And for that, I need to introduce you to that strange lady above, whose named is Eris.

We spend much of our lives, and indeed many of our happiest moments, conversing with others. I love that word, which means turning toward each other. Good conversations make us human and whole, make us feel connected to others and bring us closer to the truth of something (or at least further from a fallacy).

Unfortunately, we also spend at least as much time in bad conversations. You know them:

- bickering between husbands and wives

- political “debates” on Fox, or indeed almost anywhere else.

- Cross-examinations in courtrooms,

- and on and on and on

Those “conversations”, which are really a turning away from one another, do the opposite of what good conversations do: They leave us depleted, down, disconnected, alienated, sleazy, yucky.

What is the difference between the good and the bad conversations? Socrates told us, by giving us two new words:

- dialectic (=good), and

- eristic (=bad)

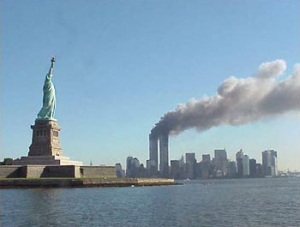

Meet Eris, the Ur-Bitch

So now it’s time for a story. It’s the most famous of the many stories about Eris, whose Roman name was Discordia.

Eris was the goddess of strife. Nobody liked her, so when the future parents of Achilles had their wedding, everybody was invited except Eris. Eris fumed.

She knew what she was good at, and did it: She left a golden apple lying around the wedding party. It said “To the most beautiful”. How cunning, how feminine.

Three extremely beautiful goddesses, Hera, Athena and Aphrodite, immediately started bickering about who had rights to the apple. It was decided to appoint a judge, somebody sufficiently hapless, naive and male to be easily manipulated. They settled on Paris, a prince of Troy.

“Paris,” whispered Athena, “don’t you think I’m the most beautiful? I’m the goddess of wisdom, as you know, and I could be persuaded to make you the wisest man alive.”

“Choose me,” said Hera, “I’m the wife of Zeus and can make you the most powerful man in the whole world.”

“Oh, Paris,” cooed Aphrodite with a tiny bat of her languorous eyelids. “You know who I am, don’t you? We all know that the apple is mine. Say so, and I will give you the most beautiful woman in the world.”

Paris, with the priorities of the average teenager, chose Aphrodite. Athena and Hera were fuming. Hatred descended on the wedding party. And everybody knew that Paris was now to get Helen, the most beautiful of the mortal women.

The only problem: Helen was already married, to a Spartan who was the brother of the great king Agamemnon. Agamemnon and his Greeks would have to come after Paris and his Trojans to get Helen back. Ten years of bloody war followed. Eris had outdone herself.

Eristic conversation

So Socrates chooses to call bad conversations eristic. They are full of strife, because–and this is the key–they are conversations in which each side wants above all to win. Where there is a winner, there is usually a loser, so these conversations separate us.

The opposite was dialectic, whence our word dialogue, the Greek form of the Latin conversation (ie, turning toward). When you turn toward another, you are not trying to win, you are trying to find the truth. That is your motivation, and it is one you share with your conversation partner (as opposed to opponent). Everybody wins, as long as you climb higher through your conversing, toward more understanding or more communion.

We today

I mentioned in the previous post a series of serendipitous events recently. The first was an email from Cheri Block Sabraw, a writing teacher and reader of The Hannibal Blog, that pointed me to this essay, “Notes on Dialogue”, by a great intellect named Stringfellow Barr.

Written in 1968, it might as well have been penned today, as Barr describes eristic and dialectic conversation in our own world:

There is a pathos in television dialogue: the rapid exchange of monologues that fail to find the issue, like ships passing in the night; the reiterated preface, “I think that . . .,” as if it mattered who held which opinion rather than which opinion is worth holding; the impressive personal vanity that prevents each “discussant” from really listening to another speaker and that compels him to use this God-given pause to compose his own next monologue…

Expressing the Socratic ideal, Barr says that

We yearn, not always consciously, to commune with other persons, to learn with them by joint search,

and that

the most relevant sort of dialogue, though perhaps the most difficult, for twentieth century men to achieve and especially for Americans to achieve is the Socratic….

What makes good (Socratic) conversations good? They have a completely different dynamic than bad conversations. They tend to be

- poor in long-winded declarations and rich in short, pithy back-and-forth,

- egalitarian in that it does not matter who says what but what is said (even though this does not mean “equal time” for any nonsense)

- spontaneous, in that they follow wherever the argument leads, even and especially to surprising destinations,

- playful, and indeed humorous, for that is what makes “serious” investigation possible and sublime.

In short, this sort of conversation is what The Hannibal Blog is about, with the amazing input by all of you in the comments that make each topic come alive. If The Hannibal Blog is against anything, it is Eris and her spawn.

And so I leave you with just one famous instance when two fakers were called to account and told just what sort of “conversation” they dealt in:

1) What is sleep?

1) What is sleep?

What is money?

What is money?